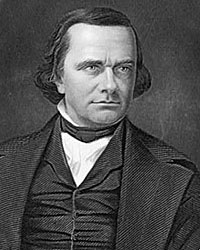

Known as “Little,” Stephen A. Douglas was an Illinois Senator (1847-61, Democrat) and the leading proponent of “popular sovereignty” as the solution to slavery in U.S. territories. Douglas ran for President as candidate of Northern Democrats in 1860 but advocacy of “Freeport Doctrine” in his 1858 Senate race against Abraham Lincoln doomed any possibility of Southern Democrat support or Democratic victory. He narrowly won the Senate race after a series of seven famous debates. His 1860 nomination for President split the Democratic party; Douglas ran second in the popular vote but received only 12 Electoral College votes.

“There had always been a feeling of friendship existing between Mr. Lincoln and Judge Douglas; and the manner in which the latter acted just prior to the Inauguration, and the gallant part he sustained at that time, as well as afterwards, served to increase their mutual regard and esteem. It was my good fortune to stand by Mr. Douglas during the reading of the Inaugural of President Lincoln,” wrote New York Times correspondent Joseph Howard, Jr.. “Rumors had been current that there would be trouble at that time, and much anxiety was felt by the authorities and the friends of Mr. Lincoln as to the result. ‘I shall be there,’ said Douglas, ‘and if any man attacks Lincoln, he attacks me, too.’ As Mr. Lincoln proceeded with his address, Judge Douglas repeatedly remarked ‘Good!’ ‘That’s fair!’ ‘No backing out there!’ ‘That’s a good point!’ etc., indicating his approval of its tone, as subsequently he congratulated the reader and endorsed the document.”1

Senator Douglas escorted Mary Todd Lincoln to the First Inaugural Ball in March 1861. On the first presidential levee, the New York Times reported: “Here one minute, there the next – now congratulating the President, then complimenting Mrs. Lincoln; bowing and scraping and shaking hands, smiling, laughing, yarning, and saluting the people who known him, he was a pleasant sight to behold. He deserves credit for doing a great deal of good for the administration by setting a good example to his followers and, as he is unable to hoodwink Old Abe or honeyfugle Madam L., we, as good, sound Union men, should be thankful that Douglas is inclined, as he says, ‘to play the part of the patriot.”2 Indeed, the day after the Confederates captured Fort Sumter, Douglas told John Forney: “We must fight for our country and forget our differences. There can be but two parties – the party of patriots and the party of traitors. We belong to the first.”3

Douglas criticized the President’s policies on secession during March but after the surrender of Fort Sumner, Senator Douglas met with President Lincoln on April 14, 1861 to discuss his solidarity on defending the Union. Douglas biographer Damon Wells wrote: “On the evening of the Sunday that Washington learned of Sumter’s fall, Douglas drove to the White House to call on President Lincoln. He stayed for more than two hours. Once more the President took his old rival into his confidence and showed him the order that he was about to issue calling for 75,000 volunteers. Douglas came back with the suggestion that the figure should be 200,00 and added, ‘You do not know the dishonest purposes of those men as I do.”4 Congressman George Ashmun later reported that President Lincoln “drew from a drawer and read the proclamation he meant to issue next day. Rising from his chair, Douglas spoke in great earnestness, saying that he concurred in ‘every word’ of the proclamation, except that he would have called out 200,00 men instead of 75,000.”5

According to historian Robert W. Johannsen, “Moving to a map on the wall, Douglas indicated the principal strategic points which he thought should be strengthened at once. Fortress Monroe, Washington, Harper’s Ferry and Cairo. He told Lincoln of the possibility of trouble in moving troops across Maryland to Washington and suggested that they be brought by way of Havre de Grace and Annapolis. The two men conferred for nearly two hours, their interview marked by a ‘cordial feeling of a united, friendly, and patriotic purpose.’ Douglas later penned a report of his discussion with the President which he released to the press. ‘The substance of the conversation,’ he wrote, ‘was that while Mr D was unalterably opposed to the administration on all its political issues, he was prepared to sustain the president to the exercise of all his constitutional functions to preserve the union, and maintain the government, and defend the Federal Capital. A firm policy and prompt action was necessary.’ Striking a note of concord, he added that he and Lincoln ‘spoke of the present & future, without reference to the past.'”6

Douglas, who owned a Mississippi plantation and slaves, returned to Illinois to mobilize Union support and died in June 1861. Douglas gave a speech in Chicago where he said: “There can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots or traitors are but two parties, the party of patriots and the party of traitors. [Democrats] belong to the first.”7 When Douglas died in early June, 1861, he was succeeded by Republican Orville H. Browning.

Douglas was a prosecuting attorney when Lincoln first began law practice in Springfield and a later Supreme Court judge before which Lincoln practiced. He was a strong supporter of transcontinental railroad and westward development that contributed to his positions on Nebraska Compromise. Peripatetic and energetic, Douglas had a greater passion for action than for scruples. Hard-driving, hard-drinking, hard-spending, profane-speaking, a party loyalist, ambitious and bold, Douglas had alienated President James Buchanan and slavery interests which were critical to his presidential ambitions. He was dedicated both to his pursuit of the Presidency and the expansion of the country to the West.

Footnotes

- Allen C. Clark, Abraham Lincoln in the National Capital, p. 15.

- Frank van der Linden, Lincoln, The Road to War, p. 220.

- John W. Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, p. 225.

- Damon Wells, Stephen Douglas: The Last Years, 1857-1861, p. 281.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Springfield to Gettysburg, p. 377.

- Robert W. Johannsen, Stephen Douglas, pp. 859-860.

- Randall, Lincoln the President: Springfield to Gettysburg, p. 378.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

Orville Hickman Browning

The Capitol

Life of Stephen A Douglas

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1860

Transition to the Presidency (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Chicago

Kansas-Nebraska and the Senate (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Opponents and Enemies (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas and Their Friend John Calhoun

Lincoln at :Peoria: The Turning Point