The home of the President’s Secretary of State faced Lafayette Park on Madison Place near Pennsylvania Avenue. The three-story building had an impressive history long before President made his frequent visits. The “Old Clubhouse” had been built in 1830 by Commodore John Rodgers, later made over it a boarding house before it was turned into the “Washington Club.” In 1859, Congressman Dan Sickles shot Philip Barton Key as he walked across Lafayette Park to the Club. Key, whom Sickles correctly believed was having an affair with his wife, died in one of the Club’s first floor rooms, which later became the Sewards’ parlor.

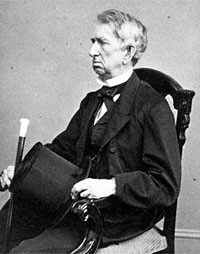

The Sewards moved into their new home shortly after the surrender of Fort Sumter in April 1861. Biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “It was only natural that the new Secretary of State should find a new Washington home, one comfortably close to the State Department. It was a spacious, red brick, three-stories-plus-a-dormer floor mansion, facing on Lafayette Square just east and north of the White House. Built some forty years before by Commodore John Rodgers on land that had belonged to Henry Clay, it had housed various Cabinet members and had served for a time as a club house or ‘mess’ for Congressmen. Seward rented it, unfurnished, for $1800 a year, the owner offering to do some painting and papering, put in city water and gas fixtures, and make other alterations which eventually included a furnace. Renting arrangements were concluded in February and the place was ready for occupancy some two months later. There were so many trees about it that its occupants could not see other houses, or even into the park,” wrote biographer Glyndon Van Deusen. Seward’s daughter-in-law, “Anna Seward saw to settling the new establishment, with Seward furniture, old and new, with portraits of Washington, Jackson, Webster, a clock, candlesticks, and other items all borrowed from the State Department, and with two mirrors, two small gilt tables, and a round extension dining table purchased from Mrs. [William] Gwin. There was china enough for twenty-four settings, a necessary item for one who entertained as lavishly and as often as did the head of the household.”1Anna Seward was different from her mother-in-law: “Unlike Frances, Anna loved the bustle of Seward’s life. ‘For six or eight nights we had visitors at all hours,’ she cheerfully reported.”2

Seward was convivial and his home was a social center for Washington. Early in the Administration, Secretary Seward volunteered to take responsibility for two state dinners, one involving entertaining Prince Napoleon’s entourage. Mrs. Lincoln objected strenuously, however, both because she disliked Seward and even more disliked any infringement on her prerogatives. According to Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, after objecting, Mrs. Lincoln “at once caused one of the private secretaries to be summoned and charged with arranging for a formal dinner on the day of the Prince’s presentation to the President. It was at the same time settled that Mr. Seward should give an evening reception in honor of the Prince on a subsequent day.”3

Seward’s home was the frequent target of evening walks by the President in search of congenial company if not the less congenial smell of William H. Seward’s ever-present cigars. They swapped off-color stories and views on the problems of the country. Mrs. Lincoln did not accompany her husband on these visits because she viewed Seward as a “dirty abolition sneak.” She even preferred not to drive by the Seward house and declined to see Mrs. Seward when she paid a courtesy call at the White House in September 1861. For the President, these visits combined business and pleasure.

William Howard Russell, a correspondent of the London Times whose writing had been highly criticized in the North, related one such visit. On November 14, 1862, Russell dined at Seward’s with Henry Raymond of the New York Times when the President arrived and told a few stories. “Here, Mr. President, we have got the two Times – of New York and of London – if they would only do what is right and what we want, all will go well,” said one of the guests. President Lincoln replied: “Yes, if the bad Times would go where we want the, good Times would be sure to follow.”4

Seward had bought the brick townhouse in 1861 and most of his family came to live there in May – with the exception of his wife, Frances, who stayed in Auburn, New York, with their daughter Fanny. According to journalist Noah Brooks, “The Secretary of State does not keep great state at his residence, although his upstairs parlors were quite tastefully furnished — marble busts, engravings, flowers , and paintings being the most noticeable objects in the room, unless it was the prodigious nose of Seward. He advanced from the rear of the parlors [at an early reception] as a batch of names was called, shaking hands with all his matchless suavitir in modo as each caller was presented. With a few kind words the visitor was passed over to Fred W. Seward, Assistant Secretary of State, a nice young man with black hair and whiskers.”5

Not every visitor was as complimentary of Seward – or the President. In a letter to his wife on November 17, 1861, the army’s commanding general, George B. McClellan, revealed his deep disdain to civilian authority over the army and the President in particular:

I went to the White House shortly after tea where I found ‘the original gorilla,’ about as intelligent as ever. What a specimen to be at the head of our affairs now! I then went to the Prince de Joinville’s – we went up stairs & had a long confidential talk upon politics etc. He showed me some letters from his mother, & his brothers d’Aumale & Nemours, which gave me important information as to the relations of France & England. He, the Prince, is a noble character – one whom I shall be glad to have you know well – he bears adversity so well & so uncomplainingly. I admire him more than almost any one I have ever met with — he is true as steel – like all deaf men very reflective – says but little & that always to the point….

After I left the Prince’s I went to Seward’s, where I found the ‘Gorilla’ again, & was of course much edified by his anecdotes – ever apropos, & ever unworthy of one holding his high position. I spent some time there & almost organized a little quarrel with that poor little varlet Seward by giving him the information I had received from the Prince (without telling the source) – he said he knew it was not so. I said I thought I was right – he again contradicted me & I told him that the future would prove the correctness of my story. It is a terrible dispensation of Providence that so weak & cowardly a thing as that should now control our foreign relations – unhappily the Presdt is not much better, except that he is honest & means well. I suppose our country has richly merited some great punishment, else we should not now have such wretched triflers at the head of affairs….

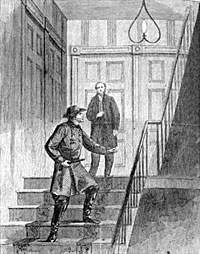

As I parted from the Presdt on Seward’s steps he said that it had been suggested to him that it was no more safe for me than for him to walk out at night without some attendants; I told him that I felt no fear, that no one would take the trouble to interfere with me, on which he deigned to remark that they would probably give more for my scalp at Richmond than for his… 6

When Republicans Senators decided to call for Seward’s scalp in December 1862, New York Sen. Preston King rushed to Seward’s home to warn him. “They may do as they please about me, but they shall not put the President in a false position on my account,” replied Seward before he wrote out his resignation. When the President received it, he hurried across Lafayette Park and told the Secretary of State: “Ah, yes, Governor, that will do very well for you, but I am like the starling in Sterne’s story, ‘I can’t get out.'” On another, more pleasant occasion, the President and John Hay walked over to his house to express their amusement with a Portuguese language manual entitled English as She is Spoke.7

On November 10, two days after the 1864 presidential elections, the Secretary of State responded to a group of serenaders outside his outside and spoke about the implications of the election: “The election has placed our President beyond the pale of human envy or human harm, as he is above the pale of ambition. Henceforth all men will come to see him as you and I have seen him – a true, loyal, patient, patriotic, and benevolent man…. Abraham Lincoln will take his place with Washington and Franklin and Jefferson and Adams and Jackson, among the benefactors of the country and of the human race.”8

In early April 1865, President Lincoln was in Richmond when he heard that Secretary Seward had been injured in a carriage accident. Lincoln cut short his visit to return to Washington, noted artist Francis Carpenter: “Mr. Lincoln’s first visit was to the house of the Secretary, who was confined to his bed by his injuries . After a words of sympathy and condolence, with a countenance beaming with joy and satisfaction, he entered upon an account of his visit to Richmond, and the glorious success of Grant, – throwing himself, in his almost boyish exultation, at full length across the bed, supporting his head upon one hand, and in this manner reciting the story of the collapse of the Rebellion. Concluding, he lifted himself up and said: ‘And now for a day of Thanksgiving!’ Mr. Seward entered fully into his feelings, but observed, with characteristic caution, that the issue between Sherman and Johnston had not yet been decided, and a premature celebration might have the effect to nerve the remaining army of the Confederacy to greater desperation. He advised, therefore, no official designation of a day ‘until the result of Sherman’s combination was known.'” Admitting the force of the Secretary’s view, Mr. Lincoln reluctantly gave up the purpose, and three days later suffered in his own person the last, most atrocious, but culminating act of most wicked of all rebellions recorded on the pages of history! It was the last interview on earth between President and his Secretary of State.”9

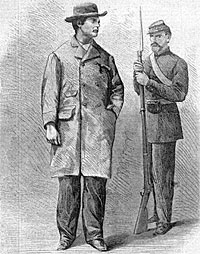

On the night of April 14, 1865, the house entered history again when Lewis Paine, an accomplice of John Wilkes Booth, entered it in an attempt to assassinate Secretary of State Seward, who was bedridden after a carriage accident. Paine assaulted a black servant who answered the door, beat Seward’s son Frederick, slashed at the father in his bedroom, battled another son Augustus and a male nurse, before fleeing Seward’s house.

Frederick W. Seward recalled that all the physicians had departed. “The gaslights were turned low, and all was quiet. In the sick-room of my father were his daughter Fanny and the invalid soldier nurse George T. Robinson. The other members of the family had gone to their respective rooms to rest, before their term of watching.”

There seemed nothing unusual in the occurrence, when a tall, well dressed, but unknown man presented himself below and, informing the servant he had brought a message from the doctor, was allowed to come up the stairs.

Hearing the noise of footsteps in the hall, I came out and met. When he told me that he came with a message from the doctor that was to be delivered to Mr. Seward personally, I told him that the Secretary was sleeping, and must not be disturbed, and that he could give me the message.

He repeated two or three times that he must see Mr. Seward personally. As he seemed to have nothing else to say, he gave me the impression that he was rather dull or stupid.

Finally, I said, ‘Well, if you will not give me the message, go back and tell the doctor I refused to let you see Mr. Seward.”

As he stood apparently irresolute, I said, “I am his son, and the Assistant Secretary of State. Go back and tell the doctor that I refused to let you go into the sickroom, because Mr. Seward was sleeping.”

He replied, ‘Very well, sir, I will go,” and, turning away, took two or three steps down the stairs.

Suddenly turning again, he sprang up and forward, having drawn a Navy revolver, which he levelled, with a muttered oath, at my head, and pulled the trigger.

And now, in swift succession, like the scenes of some hideous dream, came the bloody incidents of the night, – of the pistol missing fire, – of the struggle in the dimly lighted hall, between the armed man and the unarmed one, – of the blow which broke the pistol of the one, and fractured the skull of the other, – of the bursting in of the door, – of the mad rush of the assassin to the bedside, and his savage slashing, with a bowie knife, at the face and throat of the helpless Secretary, instantly reddening the white bandages with streams of blood, – of the screams of the daughter for help, – of the attempt of the invalid soldier nurse to drag the assailant from his victim, receiving sharp wounds himself in return, – of the noise made by the awaking household, inspiring the assassin with hasty impulse to escape, leaving his work done or undone, of his frantic rush down the stair, cutting and slashing at all whom he found in his way, wounding one in the face, and stabbing another in the back, – of his escape through the open doorway, – and his flight on horseback down the avenue.”10

Booth biographer Michael W. Kauffman wrote: “Awakened by Fanny’s screams, Augustus Seward…was jolted from sleep in a nearby bedroom and joined the scuffle. He and Robinson forced the madman toward the door. While the nurse pinned him down, Augustus ran to get his revolver. That was the assailant’s chance to escape. He leaped to his feet, throwing Robinson to the side, and stumbled out of the room. He was barreling down the stairs when a State Department messenger unexpectedly blocked his way. Emrick Hansell was about to run for help, but the assassin was moving quickly, and he knocked Hansell to the floor, stabbing him in the back for good measure. Fleeing outside, bellowing ‘I’m made! I’m made!’ the man ran to a waiting horse.”11

Frederick Seward recalled: “Five minutes later, the aroused household were gazing horrified at the bleeding faces and figures in their midst, were lifting the insensible form of the Secretary from a pool of blood, – and sending for surgical help. Meanwhile a panic-stricken crowd were surging in from the street to the hall and rooms below, vainly inquiring or wildly conjecturing what had happened. For these, the horrors of the night seemed to culminate when later comers rushed in, with the intelligence that the President had also been attacked, at the same hour, – had been shot at Ford’s Theatre, – had been carried to a house in Tenth Street, – and was lying there unconscious and dying.”12 The doctor who responded to the attack reported that Seward looked like a “corpse. In approaching him my feet went deep in blood. Blood was steaming from an extensive gash in his swollen cheek; the cheek was now laid open.”13

Frederick was the most dangerously wounded and remained in a coma for several days. However, it was Seward’s wife Frances, who was not present in Washington at the time of the attempted assassination, whose health was most endangered. She came from the Sewards’ Auburn home to nurse the family but soon needed nursing herself and died on June 21. Everyone else recovered although Seward’s life was in danger for several days.

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton was particularly solicitous. Anthony Pitch wrote that after the Seward accident, Stanton “sat by the bedside….[He] wiped blood from the lips of his cabinet colleague. He comforted and consoled with such tenderness that Fanny thought he acted ‘like a woman in the sick room, much more efficient than I, who did not know what to do.’”14

On the night of the assassination, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton both were in their nearby homes when they learned of the attacks on Seward and Mr. Lincoln. They both hurried first to Seward’s house where they met and proceeded to Mr. Lincoln’s bedside at the Peterson House, where they remained the rest of the night.

Footnotes

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 269.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 356.

- Paul M. Angle, The Lincoln Reader, p. 420.

- Fletcher Pratt, editor, William Howard Russell, My Diary, North and South, p. 259.

- Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, p. 61.

- Stephen Sears, Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, pp. 135-136.(Letter to Mary Ellen McClellan, November 17, 1861,)

- Frederick W. Seward, Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State, Volume III, p. 208.

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward, p. 234.

- Francis Carpenter, Six Months in the White House, p. 290.

- Seward, Reminiscences of A War-Time Statesman and Diplomat, 1830-1915, pp. 258-260

- Michael W. Kauffman, American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies, p. 24.

- Seward, Reminiscences of A War-Time Statesman and Diplomat, 1830-1915, p. 260.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 737.

- Anthony S. Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”, p. 78.

Visit

William H. Seward

Edwin M. Stanton

John Hay

George B. McClellan

Abraham Lincoln and William H. Seward

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Lafayette Park