Pennsylvania Avenue was the main paved thoroughfare in Washington, extending four miles, all the way from Rock Creek Park on the northwest to the Anacostia River on the east. It was interrupted in its path from the Capitol to the White House only by the Treasury Building. It could be an ocean of mud or a field of dust, depending on the weather. Travel along its length, which often worsened by the passage of troops and supplies through the city, was eased somewhat in July 1862 by the inauguration of horse-drawn trolley service. Pennsylvania Avenue was described by Benjamin Brown French as “one cloud of dust from end to end and it was nearly as much as one’s life was worth to pass up or down 7th St., the wind being N.W. seemed to whirl all through that street in eddies, whirling the dust in thick clouds in every direction.”1

The broad avenue was lined with gaslights and many of the city’s most prominent hotels on its northern side. The avenue was a major commercial and entertainment venue. In June 1864, Benjamin Taylor reported for the Chicago Evening Journal: “The Avenue is a museum without a Barnum, every calling has its representative man. Pantaloons kick as you pass; hand-organs dolefully grind the day out; you can buy a satin slipper one minute, and a load of hay the next. Coffins stand up on end, empty and hungry, and petition you can to get in and be composed; a transparency suggests that you be embalmed; a lantern persuades you to go to the ‘Varieties’. At the heels of a Secretary of a Department goes a shriveled itinerant with his loon-cry of ‘um-ber-ellas to mend!’ and little inky boot-blacks swarm at the crossings, and make a dive at your feet as you pass. Her a building delights in a classic portico.; there a market-house with the architecture of an old rope-walk and a brood of rickety sheds in tow, is sneaking obliquely off the Avenue, as if to get out of sight.” Taylor wrote: “The sidewalks are edged with second-hand furniture; ice-cream vendors are camped beneath the trees; index fingers point out the whereabouts of the aspiring washerwoman and the perspiring cook; among pyramids of pineapples, oranges, tomatoes through tangles of all colored humanity, from Congo to Christendom, meeting now the Beauty and now the Beast, you make your way. Oregon elbows Maine, and Great Britain and Brazil walk down the shady side in company.”2

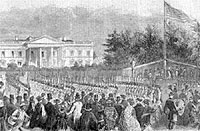

Pennsylvania Avenue was the route of inaugural parades in 1861 and 1865 — with the 1861 inaugural more tense and troubled than the celebration that accompanied the Second Inauguration in March 1865. The route to the Capitol from Willard’s Hotel in 1861 was lined with gawkers, well-wishers and job-seekers. The “parade” was the trip to Capitol Hill in which many official delegations accompanied the presidential party. The marshal of the 1861 inaugural parade route, Benjamin B. French, noted: “The inauguration ceremonies over, we escorted the new President to the white house where he received all comers with that cordial welcome that so strongly marks the sincerity of the man. In the procession was a sort of triumphal car, splendidly trimmed, ornamented and arranged, in which rode thirty-four young girls. On our return, the girls all alighted, & I took them in and introduced them to the President. He asked to be allowed to kiss them all, & he did so, It was a very interesting scene, & elicited much applause.”3 Julia Taft later noted: “Never before had Washington presented such an appearance on inauguration day. Troops lined the avenue and at every corner there was a mounted orderly. The usual applause was lacking as the President’s carriage, surrounded by a close guard of cavalry, passed and an ugly murmur punctuated by some abusive remarks followed it down the avenue.” One woman near her commented: “There goes that Illinois ape, the cursed Abolitionist. But he will never come back alive.”4

In front of the White House along the Avenue was a wrought iron fence where the President spoke on the morning after his reelection on November 8, 1864:

FRIENDS AND FELLOW-CITIZENS: Even before I had been informed by you that this compliment was paid me by loyal citizens of Pennsylvania friendly to me. I had inferred that you were of that portion of my countrymen who think that the best interests of the nation are to be subserved by the support of the present Administration. I do not pretend to say that you think so embrace all the patriotism and loyalty of the country. But I do believe, and I trust, without personal interest, that the welfare of the country does require that such support and indorsement be given. I earnestly believe that the consequences of this day’s work, if it be as you assure me and as now seems probable, will be to the last lasting advantage, if not to the very salvation, of the country. I cannot at this hour say what has been the result of the election; but, whatever it may be, I have no desire to modify this opinion–that all who have labored to-day in behalf of the Union organization, have wrought for the best interests of their country and the world, not only for the present, but for all future ages. I am thankful to God for this approval of the people. But while deeply grateful for this mark of their confidence in me, if I know my heart, my gratitude is free from any taint of personal triumph. It is no pleasure to me to triumph over any one; but I give thanks to the Almighty for this evidence of the people’s resolution to stand by free government and the rights of humanity.5

Union soldiers paraded up and down the broad avenue. Among the first was the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, which arrived in Washington after a confrontation with Confederate sympathizers in Baltimore. On April 19, 1861, “President Lincoln reviewed them from the portico of the White House,” reported Julia Taft. “My brothers and I, with the Lincoln boys, watched the review from a White House window.”6 On April 25, 1861, the Seventh New York Regiment arrived in Washington to the delight of soldiers and civilians alike. According to historian Allan Nevins, “Under a bright sun, the trim ranks of the Seventh were soon marching up Pennsylvania Avenue, whose sidewalks filled magically. The men kept soldierly step under their unstained banners, and when their band struck up onlookers danced delight. On they came, past Willard’s, past the Treasury, through the White House grounds, and under the very eaves of the mansion. Lincoln emerged to wave them a greeting, the happiest-looking man in town. As an Illinois man remarked, ‘He smiled all over.'”7

A major review of the troops came on the day that President Lincoln’s formal war message was presented to Congress — July 4, 1861. President Lincoln and General-in-Chief Winfield Scott watched from a reviewing stand on the White House grounds that was shielded by a large tent.

Pennsylvania Avenue was where the city celebrated Union victories. After the capture of Richmond on April 3, 1865, one journalist reported: “From one end of Pennsylvania Avenue to the other the air seemed to burn with the bright hues of the flag…Men embraced one another, ‘treated’ one another, made up old quarrels, renewed old friendships, marched arm-in-arm singing.”8 Good or bad news from the war were almost always recognized somewhere along the avenue. In the campaign for reelection in October 1864, the avenue was the site of a campaign parade reported by California journalist Noah Brooks: “…We had here last week…a splendid torchlight procession gotten up by the Lincoln and Johnson Club of this city. Nothing so fine has ever been seen in this city, and seldom, perhaps, has it been outdone elsewhere. Measuring by the length of the avenue, the procession was over two miles long, and it was resplendent from end to end with banners, torches, fireworks, transparencies and all of the paraphernalia of such a demonstration. Few finer sights could be shown than view of the length of Pennsylvania avenue, vanishing in the distance, gemmed with colored lights, flaming with torches, and illuminated with the lurid glare from shooting fires of red, green and blue Roman candles — the whole procession creeping like a living thing and winding its slow length around the White House, where the President looked out upon the spectacle…”9

Above all, Pennsylvania Avenue was the major east-west route of transportation in the city — a horse car line ran the length of the avenue. It was also a natural thoroughfare for thousands of soldiers — in parade or simply on the way from one encampment to another during the war. Early in the war, noted William Stoddard, “Regiment after regiment came marching gayly down Pennsylvania Avenue and passed in glittering review before him with a sort of ‘picnic and Fourth of July’ expression upon their bright and brave young faces. Those about to die saluted him as if he had summoned them to some grand holiday excursion.” Later soldiers were not necessarily so respectful – such as one New Hampshire regiment that marched down Pennsylvania Avenue on October 24, 1862: “The first halt was made in front of the White House, and at least one-third of the battalion took a vigorous account of stock. The men with bullet-proof vests–their hope and pride–in Concord–vowed that they would prefer to risk Rebel bullets rather than carry so much iron any farther. Steel breast-plates sufficient to coat a small gunboat were hurled into the gutter in front of Father Abraham’s marble cottage.”10

On their way out of military service, soldiers generally were in a better humor. Journalist Noah Brooks reported: “The one-hundred-days men from Ohio have mostly served out their time, and are now daily passing through Washington, bound home. Every one of [the] homeward bound regiments goes up to the White House and calls out the President, who makes a nice little speech; the men huzza; then the Colonel makes a nice little speech, and there are more huzzas; then the men march down the avenue feeling very good and singing the hymn whose title is the ‘subhead’ of this paragraph. These men are doubtless brave enough, but for all the good they have done they ‘had better staid at home mit the girl they love so mooch,’ as the Dutch song hath it.”11 On August 22, 1864, President Lincoln spoke a few words to these soldiers:

I suppose you are going home to see your families and friends. For the service you have done in this great struggle in which we are engaged I present you sincere thanks for myself and the country. I almost always feel inclined, when I happen to say anything to soldiers, to impress upon them in a few brief remarks the importance of success in this contest. It is not merely for to-day, but for all time to come that we should perpetuate for our children’s children this great and free government, which we have enjoyed all our lives. I beg you to remember this, not merely for my sake, but for yours. I happen temporarily to occupy this big White House. I am a living witness that any one of your children may look to come here as my father’s child has. It is in order that each of you may have through this free government which we have enjoyed, an open field and a fair chance for your industry, enterprise and intelligence; that you may all have equal privileges in the race of life, with all its desirable human aspirations. It is for this the struggle should be maintained, that we may not lose our birthright–not only for one, but for two or three years. The nation is worth fighting for, to secure such an inestimable jewel.12

Pennsylvania Avenue finally witnessed the final journey of President Lincoln’s body from the White House to the Capitol on April 19, 1865. A young soldier, Thomas Hopkins, recalled over 50 years later that of all the many historic events he had seen on Pennsylvania Avenue, “in solemnity, in the depth of feeling stirred up in the hearts of the people, in historic significance, nothing compared with this. The heavens wept when Lincoln died, but on this day Nature smiled her sweetest. The sun shone brightly, the air was balmy; the birds sang, and it seemed as if Nature were trying to comfort a stricken people.”13

South of Pennsylvania Avenue, in the area now known as the Federal Triangle, was “Murder Bay,” the center of vice, gambling and prostitution in the capital. The area closest to 14th Street was known as Hooker’s Division, a term that carried a dual meaning but did not reflect favorably on Major General Joseph Hooker. “All the vice and profligacy of all the North and West and of part of the South seem to be sewering into this great frontier post and pay-station of the army. There are more dance-houses, and all that sort of thing, than you could consent to dream of, as if the gates of hell opened always in the rear of great wars,” wrote Lincoln aide William O. Stoddard.14

Historian Donald E. Press wrote: “During the Civil War the area between Pennsylvania Avenue and the Mall reached its peak as a tough, notorious neighborhood. Early in the war thousands of volunteer troops arrived in the city either on their way south or as garrison forces. For them, Murder Bay offered quick pleasure, cheap whiskey, and, all too often, a place to be mugged and robbed. Later, former slaves found their way to Washington and squatted adjacent to the canal. The resulting squalor undoubtedly influenced newspaper correspondent Noah Brooks when he called Washington “the dirtiest and most ill-kept borough in the United States.” In fact, overcrowding became the order of the day in a wartime capital city, a circumstance that did not go unnoticed elsewhere. The New York Times cautioned its readers that Washington had drawn tens of thousands to the city, lacked sufficient hotel accommodations, and possessed a high cost of living.” The area south of Pennsylvania was a crime war zone. Historian Donald E. Press wrote: “As Washington progressed and matured, the national capital also began to experience the ills of urban life. Heavy carts and wagons tore into unpaved streets, and municipal government failed to keep up with required roadway maintenance. Often pedestrians fared little better than the wagonmasters as many sidewalks deteriorated badly before being repaired. Sanitation had become a particular problem. Pigstyes and animal pens could still be found near the heart of the city with their accompanying stench. Along with this, inadequate sewers plagued the city, causing more offensive odors, increasing disease, and permitting floods during rain-storms. Carcasses of dead animals and alleys added up to a public nuisance in some localities.”15

“The Washington Canal continued to mark the adjacent vicinity as an undesirable community,” wrote historian Donald E. Press. “Running along the north edge of the Mall, the canal had gone from bad to worse during the war years. On a hot, muggy August day its foul odors reached all the way to Pennsylvania Avenue. By 1863 the canal had sunk to such a miserable state that the secretary of the interior referred to it as “a shallow, open sewer, of about one hundred and fifty feet in width, (sometimes called a canal,) which stretches its filthy surface through the heart of the city.” He recommended a portion be covered over for exclusive use as a sewer. But it would be eight years before anyone acted on his proposal; meanwhile, the area continued to cater to man’s basest instincts.”16

Footnotes

- Donald B. Cole, editor, Benjamin Brown French: Witness to the Young Republican – a Yankee’s Journal, p. 431.

- Allen C. Clark, “Abraham Lincoln in the National Capital,” Journal of the Columbia Historical Society, Volume XXVII, p. 53 (Chicago Evening Journal, June 16, 1864).

- Benjamin Brown French, Witness to the Young Republic, pp. 348-349.

- Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, pp. 18, 20.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. VIII, p. 96.

- Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, p. 80.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Improvised War, 1861-1862, pp. 85-86.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Chronicles of the Civil War 1865, p. 66.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 140.

- Robert V. Bruce, Lincoln and the Tools of War, p. 136.

- Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, pp. 131-132.

- Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 512.

- Thomas Hopkins, in Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 488.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, William Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 35.

- Donald E. Press, “South of the Avenue: From Murder Bay to the Federal Triangle,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Volume 51, pp. 53-54.

- Press, “South of the Avenue: From Murder Bay to the Federal Triangle,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Volume 51, p. 56.

Visit