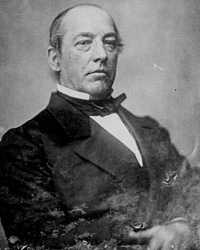

Secretary of the Interior (1861-63), Caleb B. Smith was the Chairman of the Indiana Republican delegation at the Chicago Republican National Convention in 1860 who seconded Mr. Lincoln’s nomination. His selection fulfilled an obligation unfortunately incurred by Lincoln’s managers in Chicago but provided little else to recommend it. Mrs. Lincoln opposed Illinois politician Norman Judd for the post and Mr. Lincoln told Indiana’s Schuyler Colfax that he would rather have Colfax in Congress.

Smith’s capabilities were pedestrian and he was easily recruited for the cabinet intrigues of Salmon Chase and Edwin Stanton. Congressman James G. Blaine later observed that Smith “had no aptitude for serious a task as the administration of a great department.”1 Even David Davis, who pressed for Smith’s nomination, later wrote that he had made a “great mistake” in pushing Smith for a cabinet post: “Smith repels me very much. There can be neither heart nor sincerity about him & he cannot be a man of any convictions.”2

Smith was a less easy mark for Mary Todd Lincoln, questioning her bills for White House redecoration. She, however, prevailed on Smith through John Watt to approve questionable purchases and ease her anxiety. “Smith did so by covering up the scandal,” wrote historian Michael Burlingame, but first Smith interviewed several of those involved in Mrs. Lincoln’s fiscal shenanigans, which apparently involved payments for non-existent work and materials. “According to Thurlow Weed, the Interior Department and Congress ‘measurably suppressed’ the story out of ‘respect for Mr. Lincoln.’ Congressman Benjamin Boyer of Pennsylvania confirmed Weed’s story, adding that the president paid the bill himself and withdrew the government check,” wrote Burlingame.3

Mary Todd Lincoln told her friend Orville Browning in December 1862 that Mr. Lincoln wanted to replace Smith—perhaps with Browning. Smith himself shared with Browning a different ambition—appointment to the Supreme Court. “Essentially a spellbinding party orator and jobbing politician, always indolent and now actually in poor health, Smith had little taste for his Cabinet job,” wrote Lincoln biographer Reinhold Luthin. “He hoped that Lincoln would elevate him to the United States Supreme Court, since geographically he was eligible, he thought. Secretary Smith inspired his friends in Congress to work for a law that would so ‘gerrymander’ the federal judicial circuits so as to make him eligible for the nation’s highest tribunal (United States Supreme Court justices also sat on circuit) without interfering with the ambitions of Senator Browning…”4 Instead, the appointment went to Mr. Lincoln’s former legal colleague, David Davis, whom Smith had tried maneuver into a Court of Claims judgeship.

Historian David M. Silver maintained that “there is no evidence that his candidacy was seriously considered by the President. Edward Bates explained Smith’s interest in the Court by the fact that he was the object of considerable criticism. Bates recorded in his diary: ‘I hear that there is a strong combination against him—I heard of no charge in particularly, only some alleged abuse of patronage and lack of vim. Note. He is very anxious to be translated to the Supreme Bench.’ No matter what the political considerations were, Secretary Smith was failing in health and believed that judicial duties would be less strength consuming than a post in the cabinet.”5

Smith cooperated in President Lincoln’s unworkable schemes to colonize freed slaves in Panama According to his deputy and successor, John Palmer Usher, Smith was a forceful speaker but a lukewarm supporter of emancipation:

He said to me one day when I was assistant secretary: ‘What do you think of the President issuing a proclamation abolishing slavery?’

I said: ‘I do not think well of it at this time.’

He said: ‘If he does I will resign and go home and attack the administration.’

I suppose the propriety of the first Emancipation Proclamation had been discussed, Smith having just returned from the cabinet meeting. You see what trouble Mr. Lincoln had. Smith was a man so conservative in his ideas that he felt that he could not at that time approve of a proposition to emancipate the slave in aid of the suppression of the rebellion, though when the first proclamation was issued Smith had changed his views and favored it.6

Smith was similarly ineffective in one of his other responsibilities—western Indian problems, which were badly handled by his agents in Minnesota. Smith resigned for medical reasons in December 1862 to become a U.S. District Court Judge in Indiana. He died shortly thereafter.

He had been a member of the Indiana Legislature in the 1830s and speaker of the state House of Representatives from 1835-1837. He served as a Congressman from Indiana (Whig, 1843-49) with Lincoln and sat on a panel investigating claims from the Mexican-American War. Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “Smith had been president of a Cincinnati railroad company that went bankrupt in 1857; he had also served on the Mexicoan Claims Commission, whose actions ‘stunk in the nostrils of the American people.’” Burlingame wrote that Smith “campaigned for the job, proved to be a mediocre secretary, but Indiana had been promised a seat in the cabinet and no other Hoosier commanded so much home support.” Burlingame noted: “Some considered Smith intellectually ill-equipped for a cabinet post. Henry Villard, who deplored his ‘incompetency’ and ‘worse than mediocrity,’ reported that the ‘mental caliber of that choice of the Hoosier politicians seems to be thought altogether inadequate to a creditable performance of the duties of the Secretary fo the Interior.’ Smith’s ‘only real qualification,’ he sneered, ‘is a stentorian voice.’”7

Footnotes

- Nelson Loomis, “President Lincoln’s Cabinet.” p. 7 (from James G. Blaine, Twenty Years in Congress).

- Willard L. King, Lincoln’s Manager David Davis, p. 204.

- Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 302-303.

- Reinhold H. Luthin, The Real Lincoln, p. 361.

- David M. Silver, Lincoln’s Supreme Court, p. 73-74.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 379.

- Michael Burlingame,Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume I, pp. 739-740, Volume II, p. 54.

Visit

John Palmer Usher

Schuyler Colfax

John Watt

William S. Wood

Benjamin Brown French

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

David Davis

Orville H. Browning

Leonard Swett

Biography

Abraham Lincoln and Indiana

Colonization (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)