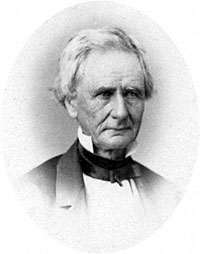

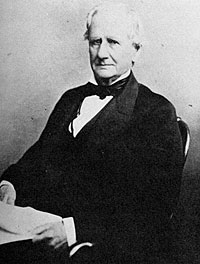

Cabinet and Vice Presidents: Simon Cameron (1799-1889)

“The Great Winnebago Chief” and “Czar of Pennsylvania,” Simon Cameron was the Pennsylvania Republican leader who served in the Senate (1845-49, 1857-61, 1867-77), and replaced James Buchanan. A former Democrat with such widespread business interests in newspapers, banking and manufacturing that he resembled a Whig in political philosophy, Cameron had been a friend and colleague of James Buchanan. He had a reputation of abandoning and manipulating the Democratic party for his own interests. In 1857, Thad Stevens decided to help return Cameron to the Senate as a Republican where he was serving when he sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1860.

After Lincoln’s election, he was first offered a cabinet post. The offer was withdrawn, then extended again. Cameron actually wanted to be Secretary of the Treasury. His nomination was pushed by Illinoisan David Davis and New Yorker Thurlow Weed for whom Cameron’s ethical problems were not disabling. Rumors of alleged corruption dated back to his alleged swindle of Indians and provided his “Great Winnebago” nickname. A split with the faction of the Pennsylvania Party headed by Andrew G. Curtin and Alexander K. McClure caused him repeated problems in reaching his political aspirations during the Civil War period. Mr. Lincoln met with Cameron twice after his arrival in Washington and finally appointed him to the cabinet on March 5, 1861, the day after the Inauguration.

One story about Cameron’s reputation is disputed but it was widely repeated during his lifetime. Mr. Lincoln reportedly asked Thaddeus Stevens about Cameron’s honesty and was told that “I do not believe he would steal a red hot stove.” When the President repeated the story, Cameron was offended and a retraction from Stevens was demanded. The crusty Republican congressman replied that he could have been wrong and thus suggesting that perhaps Cameron might steal a red hot stove. Rumors of political and financial corruption plagued Cameron throughout his career although the financial beneficiaries were usually his friends, not Cameron himself, who maintained that he could have earned much more had he remained outside politics.

John Usher, who also served in Mr. Lincoln’s cabinet, recalled a dinner party where Cameron defended himself against any involvement in corrupt contracts, saying: “If I have any ability whatever, it is an ability to make money. I do not have to steal it. I can go into the street any day, and as the world goes, make all the money I want. It was absurd to accuse me of that. When the war broke out I knew that the railroad from Baltimore to Harrisburg, the Northern Central of Pennsylvania, was bound to be good property; the soldiers and people devoted to the preservation of the Union traveling to Washington would necessarily be transported over it. The stock was then worth only a few cents on the dollar. I knew that from the very necessity of the case it would advance in value to par or nearly so. I bought large blocks of this stock, and told Mr. Lincoln if he would give me ten thousand dollars I would make him all the money he wanted.” Cameron said the President declined his offer.1

It was harder to defend himself against charges of incompetence. “We were entirely unprepared for such a conflict, and for the moment, at least, absolutely without even the simplest instruments with which to engage in war,” Cameron later remembered. “We had no guns, and even if we had, they would have been of but little use, for we had no ammunition to put in them – no powder, no saltpetre, no bullets, no anything.” 2

As a Secretary of War, he proved not very competent at organizing the logistical support of the army but far too adept at annoying the President. John Nicolay noted that Cameron was “Selfish and openly discourteous to the President. Obnoxious to the country. Incapable either of organizing details conceiving and executing general plans.”3

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote: “Determined to protect his position, Cameron sought to ingratiate himself with the increasingly powerful radical Republicans in Congress, led by Massachusetts’ Charles Sumner, Ohio’s Ben Wade, Indiana’s George Julian, and Maine’s William Fessenden. Though known as a conservative on the issue of slavery, Cameron began by degrees to embrace the radical’s contention that the central purpose of the war was to bring the institution of human bondage to an end.”4 Among the controversies in which Cameron engaged was his annual report in December 1861 which stated: “Those who make war against the Government justly forfeit all rights of property, privilege and security derived from the Constitution and laws against which they are in armed rebellion; and as the labor and service of their slaves constitute the chief property of the rebels, such property should share the common fate of war to which they have devoted the property of loyal citizens. It is as clearly the right of the Government to arm slaves when it may become necessary as it is to use gunpowder or guns taken from the enemy.”5 President Lincoln rejected this premature emancipation proclamation (which had been written by Edwin M. Stanton) and ordered copies of it recalled.

Cameron served until removal in January 1862 for mismanagement, corruption and abuse of patronage as well as unauthorized endorsement of emancipation. Cameron blamed his ejection from the Cabinet in part on General John C. Frémont, who had been dismissed from his western command a few months earlier: “It was necessary for somebody to go out and attend to Fremont. [Montgomery] Blair went first and came back and equivocated. Then they all said I must go. I told Lincoln, I understand this – Fremont has got to be turned out, and somebody will have to bear the odium of it – if I go and do it I will probably lose my place here. In that case you must give me a foreign mission. That was the beginning of the Russian Mission.” 6

Many Cabinet members claimed credit for suggesting Cameron’s replacement. Before he replaced Cameron, President Lincoln visited Secretary of State William H. Seward to talk about a successor. He had apparently settled on Edwin Stanton although as historian Doris Kearns Goodwin observed: “In the end, each of the three men– Seward, Chase, and Cameron – assumed he was instrumental in Lincoln’s appointment of the new secretary of war.”7 Cameron himself recalled: “When I went out of the Cabinet Lincoln asked me whom I wanted for my successor. I told him I wanted [Edwin M.] Stanton. Well said he go and ask Stanton whether he will take it. I started to go down and on the way I met Chase, and told him I was just going down to see Stanton – and told him what I was going for. No said he don’t go to Stanton’s office. Come with me to my office and send for Stanton to come there and we will talk it over together, and I did so.”8

A few months later, a congressional committee censured his handling of War Department purchases. President Lincoln defended Cameron and took responsibility for the irregular handling of procurement at the beginning of the war—a defense for which Cameron remained grateful. Over the objections of his critics, Cameron was confirmed as Minister to Russia where he served very briefly—spending most of his time in travels across Europe—before he traveled again to Washington in late 1862. Cameron was then replaced by his predecessor in that job, Cassius Clay.

In early 1863, Cameron narrowly lost a legislative election which would have returned him to the Senate from Pennsylvania. It was a rare occasion in his career in which Cameron was unable to manipulate the election to his favor. Still feuding with the Curtin-McClure faction of the Pennsylvania party, he sought to succeed Curtin as governor in 1863, but Curtin yielded to political pressure that he seek reelection. Cameron first encouraged a presidential candidacy of General Benjamin Butler in 1863 but played an important role in brokering support for President Lincoln in the 1864 election, helping with Butler and Republican Radicals. Allegedly under presidential instructions, he also claimed to help orchestrate a switch in the vice presidential nomination from Hannibal Hamlin to Andrew Johnson. He went on to lead President Lincoln’s campaign in Pennsylvania, but was forced to agree to the aid of his long-time political enemy, Alexander K. McClure.

Though neither a senator nor governor, Cameron managed to control a large part of the Lincoln Administration patronage in Pennsylvania. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was not admirer of patronage but he recorded in his diary that Cameron “has prevailed in the Treasury and in the Post Office, against the combined efforts of all the Members of Congress. In sustaining the policy of the President he shows sagacity.”9

After the war, Cameron was reelected to the Senate where he served as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. Always a master of political manipulation and patronage, Cameron set up the strong Pennsylvania Republican political machine—which was continued by his son, James, who followed him in office, first as Secretary of War and then as Senator.

Footnotes

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 381.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 366. (New York Times, June 3, 1878)

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 59.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 404.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The History of Abraham Lincoln, and the Overthrow of Slavery, p. 248.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, p. 43 (Conversation with Gen. Cameron, February 20, 1875).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, p. 44 (Conversation with Gen. Cameron, February 20, 1875)

- Fletcher Pratt, Stanton: Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 132.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 349.

Visit

The War Department

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Edwin M. Stanton

Hannibal Hamlin

Benjamin Butler

Alexander McClure

Andrew G. Curtin

John G. Nicolay

Thaddeus Stevens

John P. Usher

Gideon Welles

Biography

Draft of 1861 Annual Report

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania

Simon Cameron (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Cameron’s Report (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)