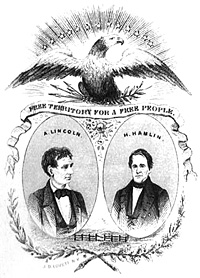

Vice President elected on 1860 Republican ticket but unexpectedly dropped on 1864 Union ticket in favor of Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee War Democrat. He had a cordial but not close relationship with the President. He exercised an important role in the selection of Lincoln’s first cabinet; he argued unsuccessfully against Seward’s inclusion in cabinet but was successful in naming Gideon Welles as New England’s cabinet representative. Hamlin played little role in President Lincoln’s first term, but did help win Mr. Lincoln’s agreement for the use of black soldiers. Hamlin was a strong supporter of Negro rights, before, during and after the Civil War. After the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, Hamlin became one of the first to pressure the President to pursue emancipation and recruitment of black soldiers as a strategy of war. He pushed for an immediate Proclamation of Emancipation in 1862.

White House etiquette did not even allow the Vice President regularly to attend cabinet meetings so unlike heads of departments, he seldom visited the White House—perhaps because he and Mary Todd Lincoln did not like each other. Aide William O. Stoddard noted: “It seems that a sort of etiquette has been established, in accordance with which it is not considered god taste for the second officer of the Republic to meddle much with public business, and which, at all events, keeps him away from the Executive Mansion.”1

Hamlin did not spend much more time in Washington during the war than necessary. He returned to Maine after his inauguration on March 4, 1861, proceeded to New York City after Fort Sumter fell, then returned to Maine, then back to New York and Washington. But he almost immediately returned to Maine, returning in time for the special session of Congress at the beginning of July. He later went to the White House. President Lincoln “was very busy, but treated me cordially and seemed pleased to see me. I think he is not sensible to just how he has treated me in certain matters, and I said nothing of it,” Hamlin wrote his wife. “He inquired particularly for you, and said his brief acquaintance with you was very pleasant, and he had formed a very high opinion of you. He must have known such kind words of my little wife were very gratifying to me – and they were.”2

Hamlin later described the Vice Presidency as a “nullity” and said “I did not obtrude upon or interfere with the Presidential duties, though I always gave [President Lincoln] my views, and when asked, my advice. His treatment of me was on his part that of kindness and consideration, and my counsels had all the more weight with him, that he thus practically knew them to be disinterested and free from any taint of intrigue or factional purpose.”3 In the summer of 1862, Hamlin complained: “The slow and unsatisfactory movement of the Government do not meet with my approbation, and that is known, and of course I am not consulted at all, nor do I think there is much disposition in any quarter to regard any counsel I may give much if at all.”4

One of few references to Hamlin’s employment by the President came in May 1861, as recorded by Lincoln aide John Hay: “The President came into Nicolays room this afternoon. He had just written a letter to Hamlin, requesting him to write him a daily letter in regard to the number of troops arriving departing or expected, each day. He said it seemed there was no certain knowledge on these subjects at the War Department, that even Genl. [Winfield Scott] was usually in the dark in respect to them.”5 Unfortunately for the President, Hamlin had gotten frustrated waiting in New York for presidential instructions and had departed before the letter arrived.

Straightforward and gregarious, well-mannered and principled, his requests for patronage appointments frequently went unfulfilled—since preference for appointments went to a state’s Republican senators. As a result Hamlin was dismayed and Mr. Lincoln irritated, as the following presidential notation indicated: “The Vice-President says I promised to make this appointment, & I suppose I must make it.”6 There was one place, however where Hamlin was even more unpopular than President Lincoln. Mr. Lincoln questioned if “the Richmond people would like to have Hannibal Hamlin here any better than myself? In that one alternative, I have an insurance on my life worth half the prairie land in Illinois.”7 For his part, Hamlin complained: “I am only a fifth wheel of a coach and can do little for my friends.”8 Even his constitutional duties to preside over the Senate bored him and he spent much of the war in Maine.

Hamlin was removed from the Union ticket in June 1864 because Republicans wanted a “War Democrat” for political balance—although President himself told one delegate “I see no reason for a change.”9 A conflict with Fessenden, who became Lincoln’s secretary of the Treasury in July 1864 only to resign in early 1865, placed Hamlin in a political bind. It would have been natural to attempt to succeed Fessenden in the Senate, which Fessenden blocked by resigning to return to his old seat. Hamlin had sought unsuccessfully to lobby President Lincoln to appoint Fessenden as Chief Justice in late 1864 in order to remove him as a rival. The President considered appointing Hamlin to succeed Fessenden at the Treasury, but Fessenden blocked that opportunity as well. “You have not been treated right. It is too bad, too bad. But what can I do? I am tied hands and feet,” lamented the President.10

Hamlin left Washington for Maine shortly after his successor took office on March 4, 1865 in a drunken scene that left many Republicans infuriated with Vice President Andrew Johnson. Hamlin and Senator James R. Doolittle had escorted Johnson to the Capitol. In the Senate chamber Hamlin gave a short, cogent speech before an unwell Johnson, fortified with whiskey, gave a long and incoherent one. Ironically, as vice president Hamlin had risked the fury of liquor-loving Senators by banning it from Senate chambers and thus had turned the Senate into a more decorous institution. Two of Hamlin’s children — Sarah and Charles — remained in Washington and were at Ford’s Theater on the night President Lincoln was assassinated five weeks later. Hamlin’s daughter Sarah, married to George Batchelder, felt a “chill passing over” as Booth lept to the stage near where she was seated.11

Vice President-elect Hamlin and President-elect Lincoln Lincoln had first met in Chicago in late November 1860 when they discussed possible members of the Lincoln cabinet. Lincoln said to Hamlin of hearing him in 1848: “Your subject was not new, but the ideas were sound. You were talking about slavery, and I now take occasion to thank you for so well expressing what were my own sentiments at that time.” Hamlin recalled being told that Lincoln was “the best story teller in the House.”12

Hamlin’s sons Charles and Cyrus were both Union generals; Hamlin himself even served briefly as a private in the Army during the Civil War. Hamlin also served as Congressman (Democrat, 1853-47) Senator from Maine (Democrat, Republican, 1848-57, 57-61, 1869-81) and Governor (Republican, 1857). He was appointed Collector of the Port of Boston in 1865 but quit a year later in disagreement with President Johnson’s reconstruction policies. By a single vote, Republicans legislators chose him to return to the Senate in 1869. His influence over the next decade was forged through support of President Ulysses Grant and an alliance with House Speaker James G. Blaine, also of Maine. He had more clout as a senator during this period than he had as vice president under President Lincoln. He later served as Minister to Spain (1881-82).

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 171 (from William Stoddard, White House Sketches, No. 7).

- Mark Scroggins, Hannibal: The Life of Abraham Lincoln’s First Vice President, p. 174.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln: John G. Nocolay’s Interviews and Essays, p. 68 (interview with Hannibal Hamlin, April 8, 1879).

- H. Draper Hunt, Hannibal Hamlin, p. 155.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 18.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 216.

- Francis Carpenter, Six Months in the White House, p. 66.

- Hunt, Hannibal Hamlin, p. 156.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 167.

- Charles Eugene Hamlin, The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin, p. 496.

- Anthony S. Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”, p. 116.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume I, p. 283, 279.

Visit

William Pitt Fessenden

Andrew Johnson

Gideon Welles

Winfield Scott

John Hay

William H. Seward

William O. Stoddard

Biography

Abraham Lincoln and Maine

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln and Chicago