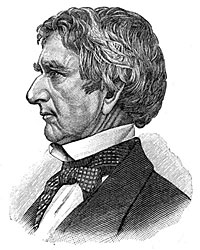

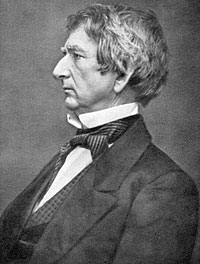

Secretary of State in Lincoln’s Cabinet, William H. Seward was the Senator from New York (Whig, Republican, 1849-61) who was the leading candidate for Republican presidential nomination in 1860. His association with New York Republican boss Thurlow Weed tainted him in the eyes of many. His support of parochial schools won him the everlasting enmity of nativists and probably cost him the Presidency. Although he called conflict “irrepressible” in 1859, he fought hard after Lincoln’s election to avoid it. Gregarious, well-read, and inveterately pragmatic, he was considered a radical before the war. He had argued for a “higher law” than the Constitution in debates over the Compromise of 1850, but he became a conspicuous moderate with the passage of time.

Seward took office with a condescending and skeptical attitude toward Mr. Lincoln. He and the President became close personal friends—to the consternation of his enemies—a relationship encouraged by the proximity of his home to the White House. According to William O. Stoddard, “Conferences between Mr. Seward and Mr. Lincoln were almost of daily occurrence, and the iron hand discernible in the conduct of our foreign affairs was not solely that of the shrewd and able head of the State Department. These conferences were generally held at the White House, to and from which Mr. Seward went and came with the easy familiarity of a household intimate rather than with any observance of useless etiquette. It was not all uncommon, however, for Mr. Lincoln to walk over to the State Department, in the daytime, or to Mr. Seward’s house, in the evening, with or without an attending private secretary to carry papers. On the whole, he generally preferred to go alone…”1

According to Seward biographer John M. Taylor, “As Lincoln and Seward became more comfortable in their relationship, the latter became a target of the president’s wit. According to Fred Seward, his father, searching for the president in the White House, once found him polishing his boots. When Seward remonstrated, telling Lincoln sternly that in Washington ‘we do not blacken our own boots,’ the president was equal to the occasion, remarking good-humoredly, “Indeed, then whose boots do you blacken, Mr. Secretary?”2 Taylor wrote:

“James Scovel, a New Jersey-born newspaper reporter who enjoyed Lincoln’s confidence, had excellent access to the White House; on occasion he was even admitted on Sunday mornings, a period normally reserved for Seward and the presidential barber. Scovel could not forget the sight of Lincoln discussing recent developments with his secretary of state. ‘Mr. Seward in conversation was slow and methodical till warmed up, when he was one of the most eloquent of talkers,’ Scovel recalled. But he thought the two made an odd couple. ‘The impression following an hour with Seward and Lincoln was surprise that the two men seemingly so unlike in habit of thought and manner of speech could act in such perfect accord.’ Even in the early months of his administration Lincoln had deferred to his secretary of state in a way that irritated men like Chase and Welles. Now, with Seward’s adroit handling of the Trent affair, Lincoln believed that his original judgment had been fully vindicated.”3

Early in the Lincoln Administration, Seward tried to subvert President Lincoln’s will regarding the resupply of Fort Sumter – leading to the following conflict with Navy Secretary Gideon Welles on April 5, 1861 which Welles detailed in his diary:

Between eleven and twelve that night, Mr. Seward and his son Frederick came to my rooms at Willard’s with a telegram from Captain Meigs at New York, stating in effect that the movements were retarded and embarrassed by conflicting order from the Secretary of the Navy. I asked an explanation, for I could not understand the nature of the telegram or its object. Mr. Seward said he supposed it related to the Powhatan and Porter’s command. I assured him he was mistaken, that Porter had no command, and that the Powhatan was the flagship, as he was aware, of the Sumter expedition. He thought there must be some mistake, and after a few moments’ conversation, with some excitement on my part, it was suggested that we had better call on the President. Before doing this, I went for Commodore Stringham, who was boarding at Willard’s and had retired for the night. When he came, my statement was confirmed by him, and he went with us, as did Mr. Frederick Seward to the President. On our way thither Mr. Seward remarked that, old as he was, he had learned a lesson from this affair, and that was, he had better attend to his own business and confine his labors to his own Department. To this I cordially assented.

The President had not retired when we reached the Executive Mansion, although it was nearly midnight. On seeing us he was surprised, and his surprise was not diminished on learning our errand. He looked first at one and then the other, and declared there was some mistake, but after again hearing the facts stated, and again looking at the telegram, he asked if I was not in error in regard to the Powhatan, – if some other vessel was not the flagship of the Sumter expedition. I assured him there was no mistake on my part; reminded him that I had read to him my confidential instructions to Captain Mercer. He said he remembered that fact, and that he approved of them, but he could not remember that the Powhatan was the vessel. Commodore Stringham confirmed my statement, but to make the matter perfectly clear to the President, I went to the Navy Department and brought and read to him the instructions. He then remembered distinctly all the facts, and turning promptly to Mr. Seward, said the Powhatan must be restored to Mercer, that on no account most the Sumter expedition fail or be interfered with Mr. Seward hesitated, remonstrated, asked if the other expedition was not quite as important, and whether that would not be defeated if the Powhatan was detached. The President said the other had time and could wait, but no time was to be lost as regarded Sumter, and he directed Mr. Seward to telegraph and return the Powhatan to Mercer without delay. Mr. Seward suggested the difficulty of getting a dispatch through and to the Navy Yard at so late an hour, but the President was imperative that it should be done.

The President then, and subsequently, informed me that Mr. Seward had his heart set on reinforcing Fort Pickens, and that between them, on Mr. Seward’s suggestion, they had arranged for supplies and reinforcements to be sent out at the same time we were fitting out vessels for Sumter, but with no intention whatever of interfering with the latter expedition. He took upon himself the whole blame, said it was carelessness, heedlessness on his part, he ought to have been more careful and attentive. President Lincoln shunned any responsibility and often declared that he, and not his Cabinet, was in fault for errors imputed to them, when I sometimes thought otherwise.4

The incident soured relations between Welles and Seward. Indeed, Seward had many enemies within the Republican Party. Some of them tried to oust him from the cabinet in December 1862 and some of whom promoted a New York Democrat for the Republican vice presidential nomination in 1864 in an attempt to deprive New Yorker Seward of his place in the cabinet. Seward also had enemies in England and France, where political leaders resented his tough stance in opposition to their assistance to the Confederacy. Only the threat of war sometimes kept the two European powers from intervening on behalf of the South. However, relations between Seward and Mr. Lincoln became warm and respectful.

President Lincoln “appears to have taken a liking to the sometimes bumptious New Yorker, appreciating both his political acumen and his willingness to accept an uncomfortable subordinate relationship. More and more odd jobs came Seward’s way: Lincoln did not believe that the responsibility belonged to the secretary of state, but would Seward examine a proposed treaty with the Delaware Indians? He would,” wrote Seward biographer Taylor.5 Other Republicans were much less comfortable with the relationship and Seward increasingly became the target of jealousy and enmity from other members of the Cabinet and many members of Congress. Seward was increasingly blamed for any bad decision made by President Lincoln or any military reverse in the field. After the Union defeat at Fredericksburg, Republican Senators met on December 17, 1862 and decided to force Seward’s removal. Senator Orville H. Browning was detained by President Lincoln the next night to talk about the situation:

I told him I was [at the Senate Caucus that day] and the day before also. Said he ‘What do these men want?’ I answered ‘I hardly know Mr President, but they are exceedingly violent towards the administration, and what we did yesterday was the gentlest thing that could be done. We had to do that or worse.’ Said he ‘They wish to get rid of me, and I am sometimes half disposed to gratify them.’ I replied Some of them do wish to get rid of you, but the fortunes of the Country are bound up with your fortunes, and you stand firmly at your post and hold the helm with a steady hand – To relinquish it now would bring upon us certain and inevitable ruin.’ Said he ‘We are now on the brink of destruction. It appears to me the Almighty is against us, and I can hardly see a ray of hope.’ I answered ‘be firm and we will yet save the Country. Do not be drive from your post. You ought to have crushed the ultra, impracticable men last summer. You could then have done it, and escaped these troubles. But we will not talk of the past. Let us be hopeful and take care of the future Mr Seward appears now to be the especial object of their hostility. Still I believe he has managed our foreign affairs as any one could have done Yet they are very bitter upon him, and some of them very bitter upon you.’ He then said ‘Why will men believe a lie, an absurd lie, that could not impose upon a child, and cling to it and repeat it in defiance of all evidence to the contrary.’ I understood this to refer to the charges against Mr Seward.

“He then added ‘the Committee is to be up to see me at 7 O’clock. Since I heard last of the proceedings of the caucus I have been more distressed than by any event of my life.’ I bade him good night, and left him.6

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recalled the events as related at a Cabinet meeting the next morning:

The President desired that what he had to communicate should not be the subject of conversation elsewhere, and proceeded to inform us that on Wednesday evening, about six o’clock, Senator Preston King and F.W. Seward came into his room, each bearing a communication. That which Mr. King presented was the resignation of the Secretary of State, and Mr. F.W. Seward handed in his own. Mr. King then informed the President that at a Republican caucus held that day a pointed and positive opposition had shown itself against the Secretary of State, which terminated in a unanimous expression, with one exception, against him and a wish for his removal. The feeding finally shaped itself into resolutions of a general character, and the appointment of a committee of nine to bear them to the President, and to communicate to him the sentiment of the Republican Senators. Mr. King, the former colleague and the personal friend of Mr. Seward, being also from the same State, felt it to be a duty to inform the Secretary at once of what had occurred. On receiving this information, which was wholly a surprise, Mr. Seward immediately wrote, and by Mr. King tendered his resignation. Mr. King suggested it would be well for the committee to wait upon the President at an early moment, and, the Secretary agreeing with him, Mr. King on Wednesday morning notified Judge Collamer, the chairman, who send word to the President that they would call at the Executive Mansion at any hour after six that evening, and the President sent word he would receive them at seven.7

Over the next two days, President Lincoln manipulated a delegation of Republican Senators and his own Cabinet so that Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase appeared to be playing a double game in the Cabinet and Congress. Chase submitted his resignation and with the resignation of Seward’s also in hand, President Lincoln decided the situation was resolved and that no further action would be taken.

Biographer Walter Stahr wrote that in the aftermath of the confrontation, Seward could write to his friend [Samuel] Blatchford that the cabinet crisis, like the Trent cris, ‘ought to be regarded as proof of the stability of the country.’ In a letter to [Henry] Sanford, Seward said that they were all merely players in a revolutionary daram. ‘The scenes are unwritten, the parts unstudied, the actors come on without notice, adn often pass off in ways unexpected.’ Seward was also magnanimous, ionviting Chase to join the family for dinner on Christmas Eve, an invitation Chase declined.”8

Twice, Seward was thrown from a carriage – once in May 1862 and again in April 1865 – and was visited at his bedside by President Lincoln after the president returned from Richmond. Lincoln chronicler Anthony Pitch wrote after the accident, “Seward was barely recognizable, his face disfigured, bloated, and bruised, with blood running from his nose and his eyes all but invisible behind the puffy, discolored flesh.” The Secretary of State’s most dutiful visitor was Secretary of War Stanton “sat by the bedside….[He] wiped blood from the lips of his cabinet colleague. He comforted and consoled with such tenderness that Fanny thought he acted ‘like a woman in the sick room, much more efficient than I, who did not know what to do.’” Pitch wrote: “Seward passed the next few days in and out of delirium, restless in his sleep, sipping only liquids, and watched over by his anxious wife, Frances, and children, all fearful that congestion or inflammation could speed his death. But four days after the accident the facile swelling subsided and he was able to speak more freely. Stanton who lived several blocks north, called three times that Palm Sunday, April 9.”9

Seward biographer Walter Stahr wrote: “Seward was the indispensable man in the Lincoln admilnistration: the man who managed to keep the European nations out of the American Civil War; the man who avoided war with Britain during the Trent crisis; the man who advised Lincoln on every aspect of domestic and foreign policy; the man who somehow kept hsi sense of humor and hope through the darkest days.”10

Seward continued in President Andrew Johnson’s Cabinet and is known for the “Seward’s Folly” purchase of Alaska from Russia. He served as a governor of New York (Whig, 1839-42) but was defeated on his first try for that office. He served as a state senator (1830-1834). Son, William H., Jr., was a Union Army general. Another son, Frederick, was assistant secretary of state and was shot in the attempted assassination of the Secretary of State the same night as President Lincoln was murdered. Seward himself was badly hurt. Ironically, it was Seward’s wife, making a rare visit to the Washington to nurse her husband, who died shortly after the murder attempts.

Footnotes

- William O. Stoddard, Abraham Lincoln: The Man and the War President, p. 265.

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right-Hand Man, p. 189.

- Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right-Hand Man,p. 187.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, pp. 23-25.

- Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right-Hand Man,p. 187.

- Howard K. Beale, editor, Diary of Orville H. Browning, Volume II, pp. 599-601.

- Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man, pp. 359-360.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, pp. 194-196.

- Anthony S. Pitch, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”, p. 78.

- Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man, pp. 546-547.

Visit

Gideon Welles

David Dixon Porter

John Hay

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

The State Department

William H. Seward’s Home

Salmon P. Chase

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

Biography (Link 3)

Abraham Lincoln and Cotton

Abraham Lincoln and William H. Seward

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1860

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Abraham Lincoln and the Radical Republicans