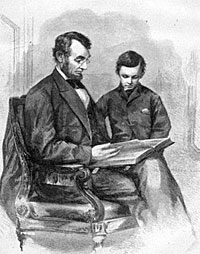

The youngest Lincoln son was named after Abraham Lincoln’s father, Thomas, but “Tad’s” nickname stemmed from his father’s belief that he resembled a tadpole at birth. He was rambunctious child who was a favorite of his father, particularly after the death of his bosom brother, Willie. According to Mary Todd Lincoln’s cousin, Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, he was “a gay, gladsome, merry, spontaneous fellow, bubbling over with innocent fun, whose laugh rang through the house, when not moved to tears. Quick in mind, and impulse, like his mother, with her naturally sunny temperament, he was the life, as also the worry of the household.”1 Julia Taft described Tad as quick-tempered; he was “very affectionate when he chose, but implacable in his dislikes.”2 White House aide William O. Stoddard described a typical scene involving the two brothers:

What a yell! But it comes from the forces belonging to quite another seat of war. Tad has been trying to make another seat of war. Tad has been trying to make a war-map of Willie, and there are rapid movements in consequence on both sides. Peace is obtained by sending them to their mother, at the other end of the building, but the President does not return to his desk. He is studying one of the maps he has pulled down from the spring-roller above the lounge on the eastern side of the room. It is an outline map of West Virginia and the mountain ranges, and it is likely that something important is going on there.3

Tad was deficient in schooling, which his father refused to impose on him. Tad didn’t learn to read until after Mr. Lincoln was murdered. A speech defect made it difficult to understand him. Nevertheless, he was beloved by many around the White House and by Union troops, whom he often saw on visits with his father. He could wear one of several military uniforms — he had been named a lieutenant by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. His exercise of military discipline over the White House staff was interrupted by his unamused older brother. What was often considered bratty by others was considered adorable by his father, to whom he was devoted. When the President would try to send him away from his office, Tad would reply: “No, no, Papa. I want to stay and see the people.”

And people loved Tad because he often championed their cause to his father. White House guard William Crook later recalled: “Taddie could never speak very plainly. He had his own language; the names that he gave some of us we like to remember to-day. The President was ‘papa-day,’ which meant ‘papa dear.’ Tom Pendel was ‘Tom Pen,’ and I was “Took.’ But for all his baby tongue he had a man’s heart, and in some things a man’s mind. I believe he was the best companion Mr. Lincoln ever had — one who always understood him, and whom he always understood.”4 Tad’s friendliness had a positive side. Historian Matthew Pinsker wrote that “The infantry guards at the Soldiers’ Home bestowed upon the youngest Lincoln an unofficial title of ‘3rd Lieutenant,’ and he became, according to their sergeant, ‘a great favorite’ of the company, appearing ‘often at drill time on his pony.’”5

Tad was less beloved by the President’s secretaries and by cabinet members, who viewed his interruptions with disdain. Historian Benjamin P. Thomas wrote: “Tad ate all the strawberries intended for a state dinner; the steward raged and tore his hair, but his mother merely asked him why he did it.”6Nevertheless, secretary John Hay recalled Tad with fondness when he wrote his obituary:

“He was so full of life and vigor — so bubbling over with health and high spirits, that he kept the house alive with his pranks and his fantastic enterprises. He was always a ‘chartered libertine,’ and after the death of his brother Willie, a prematurely serous and studious child, and the departure of Robert for college, he installed himself as the absolute tyrant of the Executive Mansion. He was idolized by both his father and mother, petted and indulged by his teachers, and fawned upon and caressed by that noisome horde of office-seekers which infested the ante-rooms of the White House. He had a very bad opinion of books and no opinion of discipline, and thought very little of any tutor who would not assist him in yoking his kids to a chair or in driving his dogs tandem over the South Lawn. He was as shrewd as he was lawless, and always knew whether he could make a tutor serviceable or not. If he found one with obstinate ideas of the superiority of grammar to kite-flying as an intellectual employment, he soon found means of getting rid of him. He had so much to do that he felt he could not waste time in learning to spell. Early in the morning you could hear his shrill pipe resounding through the dreary corridors of the Executive residence. The day passed in a rapid succession of plots and commotions, and when the President laid down his weary pen toward midnight, he generally found his infant goblin asleep under his table or roasting his curly head by the open fire-place; and the tall chief would pick up the child and trudge off to bed with the drowsy little burden on his shoulder, stooping under the doors and dodging the chandeliers. The President took infinite comfort in the child’s rude health, fresh fun, and uncontrollable boisterousness. He was pleased to see him growing up in ignorance of books, but with singularly accurate ideas of practical matters. He was a fearless rider, while yet so small that his legs stuck out horizontally from the saddle. He had that power of taming and attaching animals to himself, which seems the especial gift of kindly and unlettered natures. ‘Let him run,’ the easy-going President would say; ‘he has time enough left to learn his letters and get pokey. Bob was just such a little rascal, and now he is a very decent boy.'”7

Tad had his own special code for entering his father’s office — three quick taps and two slow bangs — but he needed no code to reach his father’s tender heart. The President virtually refused to discipline or restrain his youngest son. Tad had free rein in the house and grounds — disrupting staff, meetings, and social occasions at will. Noah Brooks wrote that, “I was once sitting with the President in the library when Tad tore into the room in search of something, and having found it, he threw himself on his father like a small thunderbolt, gave him one wild, fierce hug, and without a word, fled from the room before his father could put out a hand to detain him.”8 According to Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, “Often I sat by Tad’s father reporting to him about some important matter that I had been ordered to inquire into, and he would have this boy on his knee; and, while he would perfectly understand the report, the striking thing about him was his affection for the child.”9 Tad’s ability to manipulate and annoy others is suggested by a story told by painter Francis Carpenter who spent six months at the White House preparing a painting of the Emancipation Proclamation:

The day after the review of Burnside’s division some photographers from Brady’s Gallery came up to the White House to make some stereoscopic studies for me of the President’s office. They requested a dark closet, in which to develop the pictures; and without a thought that I was infringing upon anybody’s rights, I took them to an unoccupied room of which little ‘Tad’ had taken possession a few days before, and with the aid of a couple of the servants, had fitted up as a miniature theatre, with stage, curtains, orchestra, stalls, parquette, and all. Knowing that the use required would interfere with none of his arrangements, I led the way to his apartment.

Everything went on well, and one or two pictures had been taken, when suddenly there was an uproar. The operator came back to the office, and said that ‘Tad’ had taken great offence at the occupation of his room without his consent, and had locked the door, refusing all admission. The chemicals had been taken inside, and there was no way of getting at them, he having carried off the key. In the midst of this conversation, ‘Tad’ burst in, in a fearful passion. He laid all the blame upon me — said that I had no right to use his room, and that the men should not go in even to get their things. He had locked the door, and they should not go there again — ‘they had no business in his room!’ Mr. Lincoln had been sitting for a photograph, and was still in the chair. He said, very mildly, ‘Tad, go and unlock the door.’ Tad went off muttering into his mother’s room, refusing to obey. I followed him into the passage, but no coaxing would pacify him. Upon my return to the President, I found him still sitting patiently in the chair, from which he had not risen. He said: ‘Has not the boy opened that door?’ I replied that we could do nothing with him — he had gone off in a great pet. Mr. Lincoln’s lips came together firmly, and then, suddenly rising, he strode across the passage with the air of one bent on punishment, and disappeared in the domestic apartments. Directly he returned with the key to the theatre, which he unlocked himself. ‘There,’ said he, ‘go ahead, it is all right now.’ He then went back to his office, followed by myself, and resumed his seat. ‘Tad,’ said he, half apologetically, ‘is a peculiar child. He was violently excited when I went to him. I said, ‘Tad, do you know you are making your father a great deal of trouble?’ He burst into tears, instantly giving me up the key.’10

Tad’s instincts often mirrored his father’s in their compassion. Ward Hill Lamon recalled on occasion in which Tad took up the cause of some Kentuckians who had been waiting for several hours to see the President. He went to Mr. Lincoln’s office and requested that he be allowed to introduce some friends to the President. Mr. Lincoln agreed and Tad took them into to see the President. Tad introduced the leader and then asked him to introduce the others. According to Lamon, “The introductions were gone through with, and they turned out to be gentlemen Mr. Lincoln had been avoiding for a week. Mr. Lincoln reached for the boy, took him on his lap, kissed him, and told him it was all right, and that he had introduced his friend like a little gentleman as he was.” Tad later explained that he called the men his “friends” because “they looked so good and sorry, and said they were from Kentucky, that I thought they must be our friends.” His father replied: “That is right, my son. I would have the whole human race your friends and mine, if it were possible.”11

When the President gave his final serenade speech at the White House on April 11, Tad picked up the pages of his speech as he discarded them. When a listener suggested that the defeated Rebels should be hung, Tad said, “Oh, no, we must hang on to them.” President Lincoln responded, “That’s right, Tad, we must hang on to them.”12 Tad was not always so tender-hearted. He sometimes sentenced dolls and the family’s pet turkey to death — only to have his father issue pardons at Tad’s own request. When Tad was told his father was shot on the evening of April 14, 1865, he was understandably devastated, but bore up better than his mother. The next day, a family friend from Illinois, attorney John Albert Jones, came to the White House to pay his respects to Mrs. Lincoln According to Jones daughter, “When Tad saw my father, he ran up to him and asked: ‘Mr. Jones, wouldn’t you like to have something of my father’s?’ ‘Yes, Tad, ‘but of no value.’ Tad led my father to his father’s desk and gave him two pens, the last his father had used.”13

Two days after his father’s murder, Tad asked a White House visitor if he thought Mr. Lincoln had “gone to heaven?” When the visitor replied in the affirmative, Tad said: “I am glad he has gone there, for he never was happy after he came here. This was not a good place for him!”14

John M. Hutchinson wrote that it was “high probably that Tad had a language” defect and that it was also “likely that Tad…had some form of cleft palate, more probably a partial cleft of the soft and hard palate.”14 Born in 1853, Tad died at age 18 in Chicago of pneumonia or tuberculosis — breaking his mother’s heart once again.

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, “Six Months in the White House,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 19 (Oct.-Jan., 1926-27), pp. 48-49.

- Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, p. 8.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 12.

- Margarita Spalding Gerry, editor, Through Five Administrations: Reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook, p. 23.

- Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldier’s Home, p. 78.

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 301.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, pp. 111-112.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C. in Lincoln’s Time, p 249.

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 168.

- Francis Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, pp. 91-92.

- Ward Hill Lamon, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 167-168.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Lincoln’s Sons, p. 161.

- Eugenia Jones Hunt, “My Personal Recollections of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln,” Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, March 1945, p. 251.

- Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 293.

- John M. Hutchinson, “What was Tad Lincoln’s Speech Problem,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Winter 2010, p. 50.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

William Wallace Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln

Julia Taft

Thomas Pendel

Charles Forbes

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

John Hay’s Office

Family Library

Pets

Noah Brooks

Charles A. Dana

Ward Hill Lamon

William O. Stoddard

John Watt

Abraham Lincoln’s Sons

Stuntz Toy Shop

The White House Attic