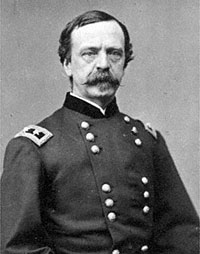

General Dan Sickles was a Congressman from New York. He shot Philip Barton Key for having an affair with his wife. Throughout his life, Sickles defended his “key” role in the Gettysburg victory and denigrated the leadership of Union General George Meade.

Sickles was seriously wounded and his leg was later amputated. He was moved to a private house in Washington to recuperate. On July 5, President Lincoln visited him. Sickles later claimed that during this visit, Mr. Lincoln related why he was confident of victory. After the Confederate invaded the North, he said he “went to my room and got down on my knees in prayer. Never before had I prayed with so much earnestness. I wish I could repeat my prayer. I felt I must put all my trust in Almighty God. He gave our people the best country ever given to man. He alone could save it from destruction. I had tried my best to do my duty and had found myself unequal to the task The burden was more than I could bear. I asked Him to help us victory now. I was sure my prayer was answered. I had no misgivings about the result at Gettysburg.”1

Historian Richard A. Sauers wrote: “While in the capital, Sickles told his version of the Battle of Gettysburg to everyone who would listen, President Lincoln included. During this recuperation period, Sickles may have begun his plan to have Meade removed from command, but it is difficult to state precisely when he first decided on this course of action. The extant references to Sickles’ stay in Washington during July 1863 do not mention exactly what Sickles told Lincoln or any of his other visitors [about???] Meade. One of Sickles’ staff officers, Lt. Col. James F. Rusling, wrote that Sickles ‘certainly got his side of Gettysburg well into the President’s mind.’”2 an address 45 years after the Civil War, Rusling recalled that Sickles had been “taken to a private residence on F Street nearly opposite to the Ebbitt House, where he had for several months reserved a floor for his own use….I found the General in much pain and distress at time, and weak and enfeebled from loss of blood; but calm and collected, and with the same iron will and clearness of intellect, that always characterized him in those Civil War days, and apparently always will.” While visiting with Sickles, his “orderly at the door announced ‘His Excellency the President’, and immediately afterwards Mr. Lincoln strode into the room, accompanied by his little son ‘Tad,’ then a lad of ten or twelve years. He was staying out at the ‘Soldiers’ Home’ for the summer with his family. But having heard of General Sickles’ arrival in Washington, he rode in on horseback, with a squad of cavalry as escort, to call upon him.”3

Sickles remained in Washington and frequently visited President or Mrs. Lincoln. Gideon Welles recorded in his diary how Sickles presented his version of the Battle of Gettysburg to Mr. Lincoln at the White House on October 20, 1863: “I met General Sickles at the President’s to-day. When I went in, the President was asking if Hancock did not select the battle-ground at Gettysburg. Sickles said he did not, but that General Howard and perhaps himself, were more entitled to that credit than any others. He then detailed particulars, making himself, however, much more conspicuous than Howard, who was really used as a set-off. The narrative was, in effect, that General Howard had taken possession of the heights and occupied on Wednesday, the 1st. He, Sickles, arrived later, between five and six P.M., and liked the position. General Meade arrived on the ground soon after, and was for abandoning the position and falling back. A council was called; Meade was earnest; Sickles left, but wrote Meade his decided opinion in favor of maintaining the position, which was finally agreed to against Meade’s judgment.”4 These attacks caused prolonged professional grief to General Meade.

Sickles, admittedly not the most reliable of observers, later said that President Lincoln claimed not to be anxious about the Battle of Gettysburg: “In the pinch of the campaign up there, when everybody seemed panic-stricken, and nobody could tell what was going to happen, oppressed by the gravity of our affairs, I went to my room one day, and I locked the door, and got down on my knees before Almighty God, and prayed to Him mightily for victory at Gettysburg. I told Him that this was His war, and our cause His cause, but we couldn’t stand another Fredericksburg or Chancellorsville. And I then and there made a solemn vow to Almighty God, that if He would stand by our boys at Gettysburg, I would stand by Him. And He did stand by your boys, and I will stand by Him. And after that (I don’t know how it was, and I can’t explain it), soon a sweet comfort crept into my soul that God Almighty had taken the whole business into his own hands and that things would go all right at Gettysburg. And that is why I had no fears about you.”5

Sickles visited the White House one night in December 1863 when there was a confrontation over Confederate sympathies of Mary Todd Lincoln’s half-sister, Emilie Todd Helm. Sickles went up to the President’s office to complain about “that rebel” in the White House. ‘Excuse me, General Sickles, my wife and I are in the habit of choosing our own guests,” responded President Lincoln. “We do not need from our friends either advice or assistance in the matter. Besides, ‘the little ‘rebel’ came because I ordered her to come, it was not of her own volition.”6

Sickles attended a seance with Mary Todd Lincoln on February 20, 1864. He was supposedly used by Mrs. Lincoln as a test for the powers of medium Nettie Colburn Maynard who identified him as “Crooked Knife,” a loose translation of Sickles’ last name. Sickles himself spoke well of the Lincolns: “In their domestic relations and in their devotion to their children, I have never seen a more congenial couple. He always looked to her for comfort and consultation in his troubles. Indeed the only joy poor Lincoln knew after reaching the White House were his wife and children. She shared all his troubles and never recovered from the culminating blow when he was assassinated.”7

Sickles was an unprincipled opportunist whose reputation was not enhanced by his comradeship with Union commander Joseph Hooker, whose vices as commander of the Army of the Potomac were well publicized. One strong view was expressed by New Yorker George Templeton Strong, who wrote that Sickles was “one of the bigger bubbles in the scum of the [legal] profession, swollen and windy, and puffed out with fetid gas.”8 Sickles had an unquestioned sense of the dramatic. After the war, he told journalist John Russell Young that the Civil War “was a Whisky Rebellion. Whisky everywhere – in the committee rooms, private houses, at a hundred saloon. There never was a State that seceded that did not secede on whisky. The debates recked with whisky. The solemn resolves of statesmanship were taken by men whose brains were feverish from whisky.”9 Sickles’ sheer gall could be amazing. As a diplomat, he took his mistress, the owner of a brothel, to meet Queen Victoria. He had an amazing ability to recover from catastrophe or near catastrophe.

Sickles got anxious waiting for a new assignment. Biographer Thomas Keneally wrote: “Dan in his restlessness, wrote on December 9 [1864] to the newly reelected President: ‘I beg respectfully to remind you that I am still unassigned….I hope to be spared the humiliation of being dropped from the rolls amongst the list of useless officers.’ The President was motivated by Dan’s part at Gettysburg to find another task for him, and asked him to him to undertake a taxming mission. Lincoln needed an emissary to go on government business to Panama and Colombia. Greater Colombia, or New Granada, as the Federation of Colombia, Costa Rica, and Panama styled itself, formed one loose federal state ruled from the highland capital of Bogotá, Colombia. He was to leave by January with the purpose of persuading the Panamanian authorities to allow Union troops to cross the Isthmus of Panama, something they had recently prohibited. He was then to travel to Bogotá and raise, with the federal authorities there, the possibility of Colombia’s offering a home to freed black slaves, who were now pooling in Washington and in northern cities. He was, in one way, well equipped in that he had as a congressman got on well with the Colombian ambassador in Washington, the bane Manuel Murillo, who was now president of Colombia.”10

He was later returned to Army service as commander of the Carolinas, from which post President Andrew Johnson removed him. President Ulysses Grant appointed him American Minister to Spain, where he managed to engage in undiplomatic relations with the queen.

Footnotes

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 574.

- Richard A. Sauers, Gettysburg: The Meade-Sickles Controversy, p. 49.

- James F. Rusling,”Sickles and Lincoln after Gettysburg; or Abraham Lincoln’s Religious Faith”.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, pp. 472-473.

- William Wolf, The Almost Chosen People, p. 125.

- Katherine Helm, Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 231.

- Stephen Sears, Controversies & Commanders, p. 198.

- Helm, The True Story of Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 195.

- May D. Russell Young, editor, Men and Memories: Personal Reminiscences by John Russell Young, p. 46.

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, pp. 310-311.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

George Meade

Emilie Todd Helm

Red Room

William H. Seward’s House

David Davis

Daniel Sickles (Mr. Lincoln and New York)