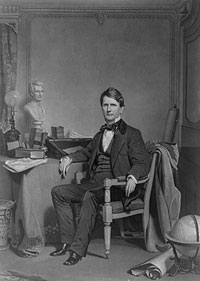

Francis P. Blair, Sr., “Father Blair,” was the founder of the (Congressional) Washington Globe in 1830, and its editor for 15 years. He was also the founder of the Republican Party in 1856. Father of General Francis P. Blair, Jr. and Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, he collectively exercised considerable influence in Missouri and Maryland. Blair was a slave owner and former Democrat who was unofficial advisor of President Lincoln. Blair was also an unofficial conduit for offering Robert E. Lee the command of the Union armies at the beginning of the war and for attempting to reach a peace agreement with Confederate President Jefferson Davis at the end of the war.

The Blair family had particularly strong links in the key border states. Francis Blair had grown up in Kentucky—where his children were born before he moved the family to Washington, D.C. and built a home in Maryland.. Montgomery Blair and Frank Blair began their professional careers as lawyers in Missouri where Montgomery was a U.S. Attorney. Montgomery moved backed to Maryland but Frank stayed in Missouri where he became an influential politician.

The elder Blair went to see President Lincoln on March 11, 1861. Biographer Elbert B. Smith wrote: “The conversation was not recorded, but after returning home, Blair was for once astounded by his own temerity at having used such passionate language to a president of the United States. ‘If I said anything which has left a bad impression on the President,’ he quickly wrote Montgomery, ‘you [must] contrive some apology for me.’ He had said ‘that the surrender of Fort Sumter, was virtually a surrender of the Union unless under irresistible force – that compounding with treason was treason to the Govt. Etc. There may be circumstances, with which I am unacquainted, rendering this very improper language & I am sure Genl Scotts patriotism, would not propose, what would warrant it. Knowing that Montgomery would hand the letter to Lincoln, Blair urged a national proclamation that would stress the defenseless condition in which Lincoln had found the government so that the fall of Fort Sumter, if should happen, would not bring disgrace on the new administration.”1

Nevertheless, Montgomery Blair despaired that President Lincoln would stand firm on Fort Sumter. “In this duel of Montgomery Blair with Seward, it momentarily seemed that Seward was winning. But the situation was suddenly changed by a dramatic intervention,” wrote historian Allan Nevins.

Blair apprised his father, the venerable Francis P. Blair, living at Silver Springs near Washington, of his probable resignation. The stalwart Jacksonian, one of the elder statesmen of the nation, a founder of the Republican Party, and a great power throughout the border area, was fiercely aroused. At the next session of the Cabinet (apparently Monday, March 18) he followed Montgomery to the White House, ensconcing himself in Nicolay’s office. At soon as the meeting broke up, he sought Lincoln, He found the president in the Cabinet room reading the written statements of the members. ‘Will you give up the fort?’ Blair demanded. Lincoln did not say. He merely replied that nearly all the Cabinet favored it.

‘It would be treason to surrender Sumter, sir,’ trumpeted the old man. He told Lincoln that the step would ‘irrevocably lose the Administration the public confidence.’ Acquiescence in secession would be a recognition of its constitutionality. Scott was timid and senile; as for Seward, the man had never known what principle and firmness meant. ‘If you abandon Sumter,’ Blair declared, in effect, ‘you will be impeached!’ And returning to Silver Springs, he wrote the President that while he did not question Scott’s patriotism, he regarded Seward as a thoroughly dangerous counselor.”2

Colonel Robert E. Lee visited Blair across the square from the White House only a few days after the surrender of Fort Sumter. Lee blunted Blair’s offer of the Union command by saying: “Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves at the South, I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native State?”3

A year later, Attorney General Edward Batesconfided to his diary about a scheme of the Blairs to revamp the Cabinet: “Seward and Stanton and perhaps Bates, indeed all except Welles, to be displaced – Chase to have Sewards place – and if that cd. not be, then Sumner to have it – Holt or Butler or Banks to have Stanton’s – and Preston King Chase’s[.] And all this to be accomplished by a very simple operation i.e. – old Mr. Blair to be the private counsellor – not to say dictator – of the President.” Bates went on to state Mr. B.[lair] complained that his father had not, of late, been admitted as much as he desired, to private conferences with the Prest….That the old man was, beyond all question, the ablest and best informed politician in America….That, under his advice, the Prest. wd. be saved a world of trouble, and the Nation far better served, than in any other way!”4

Blair had a habit of showing up at the White House or writing at times of particular crisis. One such event was during the revolt of Republican Senators in mid-December 1862. On the evening of December 14, Blair visited President Lincoln. According to historian Allan Nevin, Lincoln

…was not helped ….by some confused counsel from the elder Blair, who came to the White House that same evening—for he had doubtless heard what the Republicans were doing—and next day wrote Lincoln an emphatic letter. Perhaps Lincoln told him that Seward had resigned; more probably he did not. But Father Blair, as Lincoln called him, at any rate knew that a strong movement to reconstruct the cabinet was afoot and offered his own ideas. He urged the President to recall [George B.McClellan], get rid of Stanton, and put Preston King into the War Department. This of course would make Seward stronger than ever. The reinstatement of McClellan, thought Blair, would rally the army, which was a great political as well as military machine, behind the Administration, while the choice of King would replace the unpopular [Edwin M. Stanton] by a man of admirable judgment, business talent, and nerve, who was also politically strong in the Empire State. It need hardly be said that this scheme for putting the ultraconservatives in control was politically preposterous.

Lincoln of course knew that the proposal was in part motivated by family hatred of both [Salmon P. Chase] and Stanton. The Blairs had detested Stanton ever since the Buchanan Administration. But the Blairs also honestly thought that Preston King would make a much better head of the War Department than Stanton, an untenable opinion. ‘Pardon my zeal—it is love for the cause and you—no selfish promptings,’ concluded old Blair.5

Blair’s estate was an intellectual spa outside Washington in Silver Spring, Maryland. He supported President Lincoln’s emancipation efforts but also supported McClellan as commander in chief. His home facing Lafayette Square was subsequently owned by his son Montgomery and became famous in later years at the guest house for the White House. In November 1864 Montgomery’s father lobbied President Lincoln for the appointment of Montgomery to be chief Justice of the Supreme Court. “Although I may be stronger as an authority, if all the rest oppose I must give away,” Mr. Lincoln told the elder Blair.6

In January 1865, Blair pressed hard for presidential authority to visit Richmond in search of peace talks. John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote that Francis P. Blair, Sr., “knew better than almost any one else the individual characters and tempers of Southern leaders; and who, moreover, was ambitious to crown his remarkable career with another dazzling chapter of political intrigue, conceived that the time had arrived when he might perhaps take up the role of a successful mediator between the North and the South. He gave various hints of his desire to President Lincoln, but received neither encouragement nor opportunity to unfold his plans.”6 President Lincoln was reluctant to agree to any talks that did not recognize both the Union and emancipation, but Blair nevertheless made two trips to Richmond that led to the abortive Hampton Roads conference in early February.

Blair had been an influential editor and advisor to President Jackson. He became disgruntled with the Democratic Party in the late 1840s and supported the Free-Soil Party before helping organize the Republican Party. After the Civil War, he returned to the party of Andrew Jackson, with whom he had been intimate friends and for whom he had been a speechwriter.

Footnotes

- Elbert B. Smith, Francis Preston Blair: A Biography, p. 275.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, Volume I, p. 47.

- John William Jones, Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee, p. 13.

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, pp. 290-291 (May 10, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, Volume II, pp. 354-355.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized Road to Victory, Volume III, p. 118.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume X, p. 94

Visit

Frank P. Blair

Montgomery Blair

Salmon P. Chase

George B. McClellan

William H. Seward

John C. Fremont

Abraham Lincoln and Salmon P. Chase

Abraham Lincoln and Peace

Hampton Roads Conference