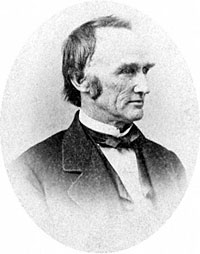

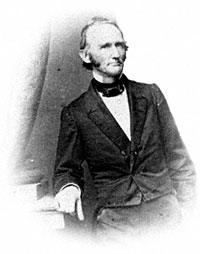

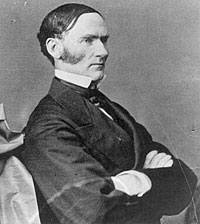

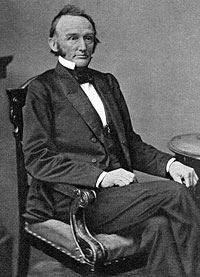

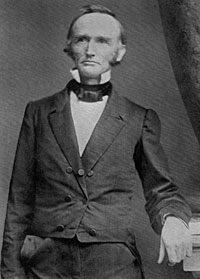

Postmaster General under Lincoln, Montgomery Blair was despised by radical Republicans and most of Lincoln’s cabinet. He was the lone hard-liner in Cabinet on Fort Sumter in 1861.

Later, he was a cantankerous opponent of emancipation and became an anathema to Radical Republicans; he resigned in September 1864 when President Lincoln needed to appease John Frémont and get the radical favorite out of the presidential race. John Hay recorded in his diary on the day of Blair’s resignation: “Blair in spite of some temporary indiscretions is a good and true man and a most valuable public officer. He stood with the President against the whole Cabinet in favor of reinforcing Fort Sumter. He stood by Frémont in his Emancipation decree though yielding when the President revoked it. He approved the Proclamation of January 1863 and the Amnesty Proclamation & and has stood like a brother beside the President always. What have injured him are his violent personal antagonisms and indiscretions.”1

Journalist Noah Brooks later noted that Blair’s “manners were awkward and unattractive. In politics he was a restless mischief-maker, and, like his brother Frank, he was apparently never so happy as when he was in hot water or was making water hot for others.”2 In October 1863, Blair made a speech in Rockville Maryland in which he attacked Radical Republicans in Congress and the Cabinet. Later in October, Blair was in the President’s office when John W. Forney strongly attacked the Rockville speech. While the President sat silently, Blair defended the speech and Forney counter-attacked: “Then, why don’t you leave the Cabinet, and not load down with your individual and peculiar sentiments the administration to which you belong?”3

Historian William Ernest Smith argued there was less difference between the Blair family that might have appeared: “The theory that Lincoln repudiated Blair because of the Rockville speech is not tenable. It is more logical to accept the opposite theory. Although he could not announce himself in favor of the Democrats in the border states, whom he distrusted, he realized that the Radical faction, which he distrusted as much as the Democrats, accepted only two phases of his policy: Freedom of the slaves, and the preservation of the Union. He was forced to choose some one whose views he accepted and in whom he could confide. Blair, who took his problems of consequence directly to the President, was the natural recipient of that confidence. Bates and Welles frequently observed his conversations with Lincoln in 1863. Frank Blair always thought that his brother talked with the President about all important matters concerning politics, the country, and the Blair family.”4

The heat from Radical Republicans dictated Montgomery Blair’s forced resignation in September 1864. Blair had resigned once before in March 1862. Blair became embarrassed by a letter he had sent General Fremont in 1861 in which he blamed the Administration’s problems on “Lincoln himself. He is of the whig school, and that brings him naturally not only to incline to the feeble policy of whigs, but to give his confidence to such advisers.’” Fremont used the letter to undermine Blair. When the letter was printed in newspapers in March 1862, Blair went to the White House to offer to resign, telling Lincoln: “I leave the whole thing to you & will do exactly as you wish.” The president told him to ‘Never mention or think of it again.” When Blair offered his resignation, Mr. Lincoln told Blair to “never mention or think of it again.”

5

Despite his sacrificial dismissal, Blair campaigned hard for the President’s reelection. He declined an ambassadorial appointment to Spain or Austria, but Blair coveted the job of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He and his family were always respectful of the President while advancing their own ambitions. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recalled how he learned of Blair’s dismissal on September 24, 1864:

Mr. Bates and myself came out of the Executive Mansion together and were holding a moment’s conversation, when Blair joined us, remarking as he did so, ‘I suppose you are both aware that my head is decapitated,—that I am no longer a member of the Cabinet.’ It was necessary he should repeat before I could comprehend what I heard. I inquired what it meant, and how long he had the subject submitted or suggested to him. He said never until to-day; that he came in this morning from Silver Spring and found this letter from the President for him. He took the letter from his pocket and read the contents,—couched in friendly terms,—reminding him that he had frequently stated he was ready to leave the Cabinet when the President thought it best, etc., etc., and informing him the time had arrived. The remark that he was willing to leave I have heard both him and Mr. Bates make more than once. It seemed to me unnecessary, for when the President desires the retirement of any one of his advisers, he would undoubtedly carry his wishes into effect. There is no Cabinet officer who would be willing to remain against the wishes or purposes of the President, whether right or wrong.

I asked Blair what led to this step, for there must be a reason for it. He said he had no doubt he was a peace-offering to Frémont and his friends. They wanted an offering, and he was the victim whose sacrifice would propitiate them. The resignation of Frémont and Cochrane was received yesterday, and the President, commenting on it, said F. had stated ‘the Administration was a failure, politically, militarily, and financially,’ that this included the Secretaries of State, Treasury, War, and Postmaster-General, and he thought the Interior, but not the Navy or the Attorney-general. As Blair and myself walked away together toward the western gate, I told him the suggestion of pacifying the partisans of Frémont might have been brought into consideration, but it was not the moving cause; that the President would never have yielded to that, except under the pressing advisement, or deceptive appeals and representations of some one to whom he had given his confidence. ‘Oh,’ said Blair,’ there is no doubt Seward was accessory to this, instigated and stimulated by Weed.’ This was the view that presented itself to my mind, the moment he informed me he was to leave, but on reflection I am not certain that Chase has not been more influential than Seward in this matter. In parting with Blair the President parts with a true friend, and he leaves no adviser so able, bold, sagacious. Honest, truthful, and sincere, he has been wise, discriminating, and correct. Governor Dennison, who is to succeed him, is, I think, a good man, and I know of no better one to have selected.6

Blair remained bitter about his dismisal — especially about Maryland Congressman Henry Winter Davis. Lincoln aide John Hay reported on the day after the election: “Montgomery Blair came in this morning. He returned from his Kentucky trip in time to vote at home. He is very bitter against the Davis clique, (whats left of it) and foolishly I think confounds the War Department and the Treasury as parties to the Winter Davis conspiracy against the president. He spoke with pleasant sarcasm of the miscalculation that has left Reverdy Johnson out in the cold, & gave an account of his ‘being taken by the insolent foe’ in the Blue Grass Region. He says he stands as yet by what he has said, that Lincoln will get an unanimous electoral vote. The soldier vote in Kentucky he thinks will save the state if the guerillas have allowed the country people peace enough to have an election.”7

An attorney in practice with his brother in St. Louis before the war, Blair had served as counsel for Dred Scott as U.S. solicitor in the Court of Claims. His opposition to Radical Republicans pushed him into the Democratic Party after the Civil War where he assisted in his brother Frank’s pursuit of higher office. He lost an effort to be elected to the Senate in February 1865 and a House race in 1882.

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 233.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, p. 41.

- Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, p. 127.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, p. 243.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 304.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles Volume II, pp. 156-57.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, pp. 246-247 (November 9, 1864)

Visit

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Frank Blair

William Dennison

Salmon P. Chase

Zachariah Chandler

John C. Frémont

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln and Maryland

Francis P. Blair, Sr.

Henry Winter Davis

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Thaddeus Stevens (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom