Gustavus V. Fox was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy who was in charge of the rescue fleet for Fort Sumter and a valued administrator of naval build-up, including the building of iron-clad ships. Fox explained his Sumter rescue plan to President Lincoln shortly after he had taken office. Previously, Fox had been a naval officer until his resignation in 1856 and then a textile businessman. Brother-in-law of Montgomery Blair, he was indefatigable and encyclopedic in naval matters. The President often consulted Fox at the White House and visited him at Fox’s home at night. Mrs. Lincoln was friendly with Fox’s wife, Virginia Woodbury Fox, to whom she often sent flowers from the White House gardens.

Fox played a leading role in the expedition to relieve Fort Sumter in April 1861. Historian David M. Potter wrote: “Fox was delayed in his final preparations and did not get under way for Charleston until the morning of April 9. Even then, incredibly, he left without having been told where the Powhatan was headed. Stormy weather delayed his arrival off Charleston until April 12, and then more time was spent waiting in vain for the Powhatan. Before he could organize any kind of effort to reach Fort Sumter, it had been pounded into submission.”1 President Lincoln absolved Fox of blame for the failure of the expedition to resupply Fort Sumter: “I sincerely regret that the failure of the late attempt to provision Fort-Sumpter, should be the source of any annoyance to you. The practicability of your plan was not, in fact, brought to a test. By reason of a gale, well known in advance to be possible, and not improbable, the tugs, an essential part of the plan, never reached the ground; while, by an accident, for whichyou were in no wise responsible, and possibly I, to some extent was, you were deprived of a war vessel with her men, which you deemed of great importance to the enterprize.”2

“Fox was vocal, outgoing, brusque at times, impatient; he enjoyed good company, good food, good wines. Even such a bon vivant as young John Hay, the President’s junior secretary deferred to Fox, when it came to exotic beverages or unusual dishes. Seward, a kindred spirit, delighted in entertaining Fox because he was so sincerely appreciative of the fine cuisine which always graced the Secretary’s table. In a social setting, Fox was a delightful companion who fairly charmed the Lincolns,” wrote John Niven, biographer of Gideon Welles. “Thought to be the brains and the guiding force of the department, [Fox] was quite unfairly charged on many occasions with decisions that his chief had made or errors that were the Secretary’s responsibility. Yet he was intensely loyal, never complaining if unjustly accused—a quality that Welles prized above all his other capabilities.”3 In November 1861 presidential aide John Hay called Fox “an incarnation of inexorable energy, is wearing out a powerful mind and an iron constitution, in relentless and unceasing labor for the cause to which he is heart and soul devoted.”4

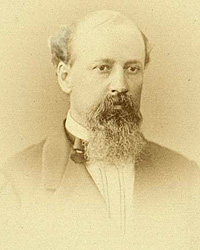

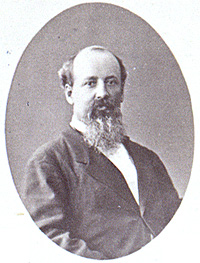

Historian Nelson D. Lankford noted that “the balding Fox sported a luxurious dark beard and mustache that concealed his expression. A bon vivant, fond of rich dinners and good cigars, he bubbled over with contempt for set patterns and old ways.”5 Historian Craig L. Symonds wrote that “Fox was nor particularly martial in appearance: he was of medium stature with a broad face, a high forehead, and dark, piercing eyes above a pear-shaped body.” Symonds noted: “Though Fox had served as a naval officer for fifteen years, including a circumnavigation of the globe in the early 1850s, he had left the navy in 1853 to pursue more lucrative employment and was now a private citizens.”6

Geoffrey Perret observed that Fox “was a sailor who knew and understood commercial shipping and had some experience of naval logistics from the Mexican War. No fighting sailor, then, yet he was allowed by Welles to push bad ideas on the Navy over the advice of combat-hardened commanders.”7 Historian Chester Hearn wrote: “Fox manifested all the characteristics of a small but highly charged human dynamo. Having served eighteen years as a naval officer, he was intimately acquainted with naval technology…Unlike Welles, he could not sit at a desk, and he displayed a lively sense of humor that kept subordinates in the department infused by his energy and wit. Fox jumped to conclusions where Welles remained thoughtful, and whatever qualities one man lacked the other abundantly provided.”8

Welles biographer John Niven wrote: “Fox was vocal, outgoing, brusque at times, impatient; he enjoyed good company, good food, good wines. Even such a bon vivant as young John Hay, the President’s junior secretary deferred to Fox, when it came to exotic beverages or unusual dishes. Seward, a kindred spirit, delighted in entertaining Fox because he was so sincerely appreciative of the fine cuisine which always graced the Secretary’s table. In a social setting, Fox was a delightful companion who fairly charmed the Lincolns.”blockquote>But if Fox advanced the cause of the Navy at the White House and among a select group of Cabinet members and Congressmen, he was too strong a personality, too positive in his opinions, too lacking in discretion not to attract enemies in the service and in the government. Impatient Congressmen may have written off Welles many times, but he had few real enemies. In fact, those who clamored for his removal usually had a kind word for him, praising his loyalty, saying that he meant well, that he was simply too old for his vast responsibilities. With Fox it was a different matter. Thought to be the brains and the guiding force of the department, he was quite unfairly charged on many occasions with decisions that his chief had made or errors that were the Secretary’s responsibility. Yet he was intensely loyal, never complaining if unjustly accused — a quality that Welles prized above all his other capabilities.”9

For President Lincoln Fox was often a more congenial contact at the Navy Department than his strait-laced boss, Gideon Welles. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “Once the President requested me to go to the Navy Department, and see what could be done for a young friend of mine who had been in the army, and who desired to get into the navy, in order to keep his promise not to go back into the military service. And as I was discussing the ways and means, the President said, ‘Here, take this card to Captain Fox; he is the Navy Department.’ Captain Fox, although a hard worker, was rotund and rosy, the very picture of a good liver who took life easy. But he was capable of performing prodigious feats of labor, and he was a complete encyclopedia of facts and figures relating to the naval service and its collateral branches, and was ready to take up and dispose of any of the multitudinous details of the Navy Department at a moment’s notice.”10

Secretary Welles himself later recalled an incident on April 4, 1863 in which Fox was used an intermediary by those who knew that Welles would oppose their schemes:

“Had a message from the President, who wished to see me and also Assistant Secretary Fox. Found the matter in hand to be the Prussian adventurer Sybert, who was anxious his vessel should be taken into the naval service. The President said [William H. Seward] was extremely anxious this should be done and had sent Sybert to him. I inquired if he had seen Sybert. He replied that he had and that the man was now in the audience room. He learned from Seward and Sybert that he (Sybert) had a vessel of one hundred tons into which he would put a screw, if authorized would go on blockade, and would do more than the whole squadron of naval vessels. I asked the President if he gave credit to the promises of this man, whom Mr. Seward had sent to me as coming from responsible parties, though I knew none of them, had seen or heard of none but this adventurer himself. [I told him] that he had first applied to me and I would not trust or be troubled with him after a slight examination, but that I had sent him to Seward, who was then pushing forward his regulations for letters of marque, to which he knew I was opposed; and the result was Mr. Seward wanted me to take his first case, and had asked that the Assistant Secretary, Fox, should be present with Sybert. After a little further conversation, the President, instead of sending Sybert back to Seward, said he would turn him over to the Navy Department to be disposed of. This ends Mr. Seward’s first application, and probably it will be the last. Knowing my views, he had gone to the President with his protégé, and knowing my views but in the hope he might have some encouragement from Fox, had requested the President to consult with Fox as well as myself. I know not that he requested me to be excluded on account of my opposition, but he requested that the Assistant Secretary should be consulted. And Fox assures me he has never swerved from my views on this subject. It is a specimen of Seward management.”11

Fox’s judgment was sometimes flawed. He believed in using ironclads to recapture the port of Charleston, South Carolina, without army assistance. Historian John Niven wrote: “For a hardheaded ex-businessman and deepwater sailor, Fox showed a singular lack of judgment when it came to the ironclad Monitor. As wedded to design as Ericsson himself, he was blind even to its most obvious defects, deaf to its proven weaknesses in performance. In these newer vessels he was certain that the Navy would have the ultimate weapon. Fox was so self-assured, so anxious to gain fresh renown for the Navy (and, it must be added, so overworked), that he brushed aside all questions that were raised about the unique difficulties involved in an attack on Charleston. After Norfolk fell and the Merrimack was blown up by the retreating Confederates in May 1862, Fox actually suggested to Du Pont that the Monitor and the little ironclad gunboat Galena were enough to capture Charleston.”12

Fox had served in the Navy for nearly two decades before resigning in 1856.

Footnotes

- David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, p. 580.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, pp. 350-351 (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Gustavus Fox, May 1, 1861).

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 354.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, p. 155.

- Nelson D. Lankford, Cry Havoc! The Crooked Road to Civil War, 1861, p. 37.

- Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p. 10.

- Geoffrey Perret, Lincoln’s War: The Untold Story of America’s Greatest President as Commander in Chief, p. 256.

- Chester Hearn, Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, p. 46.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 354.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time, p. 39.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 261.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, pp. 424-425.

Visit

Benjamin Butler

Simon Cameron

William H. Seward

David Dixon Porter

Gideon Welles

Samuel F. Du Pont

Navy Department