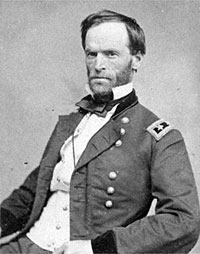

William T. Sherman, “Uncle Billy,” was a Union Army General who served under Ulysses S. Grant. He retired from the Army twice, first in 1853 and then at the outbreak of the war when he was the Superintendent of the state military academy in Louisiana. He became Superintendent of Street Railway Company in St. Louis when hostilities broke out there between pro-Union and pro-secession groups.

In March 1861, Sherman went with his younger brother, Sen. John Sherman, to visit Mr. Lincoln. “He walked into the room where the secretary to the President now sits, we found the room full of people, and Mr. Lincoln sat at the end of the table, talking with three or four gentlemen, who soon left. John walked up, shook hands, and took the chair near him, holding in his hand some papers referring to minor appointments in the State of Ohio, which formed the subject of conversation. Mr. Lincoln took the papers, said he would refer them to the proper heads of departments, and would be glad to make the appointments asked for, if not already promised. John then turned to me, and said, ‘Mr. President, this is my brother, Colonel Sherman, who is just up from Louisiana, he may give you some information you want.’ ‘Ah!’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘how are they getting along down there?’ I said, ‘They think they are getting along swimmingly – they are preparing for war.’ ‘Oh well!’ said he, ‘I guess we’ll manage to keep house.’ I was silenced, said no more to him, and we soon left. I was sadly disappointed, and remember that I broke out on John, d–ning the politicians generally, saying, ‘You have got things in a hell of a fix, and you may get them out as you best can,’ adding that the country was sleeping on a volcano that might burst forth at any minute, but that I was going to St. Louis, as the place in the Fifth Street Railroad was a sure thing, and that Mr. Lucas would rent me a good house on Locust Street, suitable for my family, for six hundred dollars a year.”1

Sherman’s attitude toward President Lincoln varied throughout the war. “General William T. Sherman had Mr. Lincoln’s respect – but not his friendship. They met briefly once in the spring of 1861 before Sherman returned to the Union Army and once again that summer. For the next four years, however, they did not cross paths – until shortly before the end of the war. In their first meeting, Sherman was disgusted by the President’s naive attitude toward the South’s secession. “There is no doubt that Lincoln’s earliest impressions of Sherman were quite as unfavorable to Sherman as were Sherman’s early impressions of Lincoln,.”wrote Pennsylvania journalist Alexander K. McClure.2

On April 6, 1861, Sherman was offered the Chief clerkship of the War Department with a promise to be made Assistant Secretary of War when Congress came back into session. Sherman declined, wishing the “Administration all success in its almost impossible task of governing this distracted and anarchial people.”3

Sherman declined appointment as a general and accepted a lower-ranking responsibility. “On May 6, his foster father, a senator from Ohio, urged Sherman to state what position he wanted so that his political allies could work with General Scott to get it; soon after, the senator met personally with President Lincoln to press Cump’s career,” wrote historian Thomas J. Goss. “This sponsoring soon paid off, and after extensive negotiations and political wrangling Sherman got his wish and was appointed as a colonel in the regular army.”4

Later in 1861, Sherman succeeded General Robert Anderson as commander in Kentucky. Historian Thomas J. Goss wrote that Sherman and the President again met before Sherman was assigned to Kentucky: “When Sherman and Anderson met the president on the eve of their assignment to that critical border state, Lincoln granted two of Sherman’s requests: he received assurances that he would not be placed in command and that his friend from his cadet days, Brigadier General George Thomas, would be assigned with him.”5

Sherman’s first efforts as commander of the Department of Cumberland were criticized, but Sherman regained his reputation by his role in turning the tide at the Battle of Shiloh. With a brilliant mind and incredible memory, he became the top aide to General Ulysses S. Grant and succeeded him when Grant took charge of the Army of the Potomac. He carried with him the stigma, however of being charged with insanity by newspapers in December 1861. In response, Sherman’s wife Ellen wrote President Lincoln: “As the minister of God to dispense justice to us and as one who has the heart to sympathize as well as power to act. I beseech you by some mark of confidence to relieve my husband from the suspicions now resting upon him.”6 In May 1862 Sherman wrote his brother: “I think Mr. Lincoln is a pure minded, honest and good man. I have all faith in him. In Congress & the cabinet there is too much of old politics, too much of old issues, and too little realization. I think it is a great mistake to stop enlistments. There may be enough on paper, but not enough in fact.”7

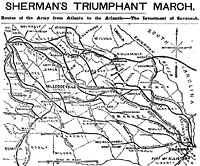

As Commander of the West, Sherman led the march to Atlanta which culminated in its siege and capture on September 1864, literally saving President Lincoln’s re-election. His march through Georgia and South Carolina devastated those regions, making him a villain in the South but simultaneously creating controversy because of Sherman’s reluctance to use Negro troops. General Sherman was beyond Union communication links during the campaign from Atlanta to Savannah and brother John Sherman recalled that when he met with Mr. Lincoln earlier in December 1864 he said: “I know what he went in at, but I can’t tell what hole he will come out of.”8 When he captured Savannah, Sherman telegraphed President Lincoln: “I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah…” In his reply, Mr. Lincoln expressed “many, many, thanks for your Christmas gift” and admitted he had been “anxious, if not fearful” of Sherman’s success.9

Sherman was a skeptic when it came to politics – and to President Lincoln. In the fall of 1864, he wrote his brother: “I got your letter about my being for McClellan. I never said so, or thought So, or gave any one the right to think so. I almost despair of a popular Government, but if we must be so inflicted I suppose Lincoln is the best choice, but I am not a voter.”,10 His attitude toward the President seemed to improve however after the President praised his capture of Savannah. Sherman wrote Grant: “Please say to the President that I received his kind message through Colonel Markland, and feel thankful for his high favor. If I disappoint him in the future, it shall not be from want of zeal or love to the cause.”11 Sherman wrote Senator Thomas Ewing, “I know full well that I enjoy the unlimited confidence of the President and Commander in Chief, and better Still of my own Army.”12 The same day, the general wrote his wife, “I did hope for some rest but all lean on me so, Grant, the President, the Army, and even the world now looks to me to strike hard & decisive blows that I cannot draw out quietly as I would and Seek rest.”13

In early January 1865, Sherman wrote President Lincoln: “I am gratified at the receipt of your letter of De[cember] 26, at the hand of General Logan, Especially to observe that you appreciate the division I made of my army, and that each part was duly proportioned to its work. The motto, ‘Nothing ventured, nothing won’ which you refer to is most appropriate, and should I venture too much and happen to lose I shall bespeak your charitable inference. I am ready for the Great Next as soon as I can complete certain preliminaries, and learn of Genl Grant his and your preferences of intermediate ‘objectives.’”14

Sherman met with President Lincoln outside Richmond a few weeks before his assassination but never again visited the White House after the spring of 1861. After their City Point conference in late March 1865, Sherman wrote his wife: “I continue to receive the highest compliments from all quarters, and have been singularly fortunate in escaping the envy & Jealousy of rivals. Indeed officers from every quarter want to join my ‘Great Army.’ Grant is the same enthusiastic friend. Mr. Lincoln at City Point was lavish in his good wishes and Since Mr. Stanton visited me at Savannah he too has become the warmest possible friend.”15

“A bundle of contradictions, occasionally all too vehement of speech [Sherman] could be the most stimulating and delightful of men in his relations with associates, and also one of the most irritating,” wrote historian Allan Nevins. “Altogether, he was the most remarkable combination of virtues and deficiencies produced in the high direction of the Union armies.”16 Among the deficiencies was a strong streak of 19th century racism. Sherman once wrote his wife: “All the Congresses on earth could not make the Negro anything else than what he was. He has to be the subject to the white man or he must amalgamate or be destroyed. The two races could not live in harmony save as master and slave.”17

Sherman became chief general of the U.S. Army in 1869, serving until 1884 when he was replaced by Philip Sheridan. He led military efforts against Indian uprisings in the West. His father-in-law was the well-connected former Ohio Senator Thomas Ewing.

Footnotes

- William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, pp. 167-168.

- Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 230.

- Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, pp. 170-171.

- Thomas J. Goss, The War Within the Union High Command, p. 68.

- Goss, The War Within the Union High Command, p. 60.

- James M. Perry, A Bohemian Brigade: The Civil War Correspondents, p. 119.

- Brooks D. Simpson and Jean V. Berlin, editors, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, p. 217 (Letter to John Sherman, May 12, 1862).

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, The Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 403.

- Roy M. Basler, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 181-182.

- Simpson and Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, p. 733 (Letter from William T. Sherman to John Sherman, October 11, 1864.

- Simpson and Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, p. 777 (Letter from William T. Sherman to Ulysses S. Grant, December 24, 1864)

- Simpson and Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, p. 782 (Letter from William T. Sherman to Thomas Ewing, December 31, 1864)

- Simpson and Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, (Letter of William T. Sherman to Ellen Ewing Sherman, December 31, 1864).

- Simpson and Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, p. 793 (Letter of William T. Sherman to Abraham Lincoln, January 6, 1865).

- Simpson and Berlin, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860-1865, (Letter of William T. Sherman to Ellen Ewing Sherman, April 5, 1865).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, Volume III, p. 27.

- Bruce Chadwick, 1858: Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, Rober/t E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant and the War They Failed to See, p. 239.

Visit

Ulysses S. Grant

David Dixon Porter

Biography (Link 2)

Memoirs of General Sherman

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

John Sherman

John A. McClernand (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Henry W. Halleck

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief