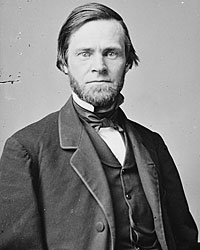

Senator from Ohio (1861-77, 1881-97, Republican), John Sherman was the attorney and businessman who served as a Congressman (1855-61), before he took Salmon P. Chase’s seat in the Senate in March 1861. He came to national attention when he was serving on a House committee investigating violence in Kansas in 1856 – and writing the committee’s report. During this period, Sherman was an organizer of the state and national Republican parties.

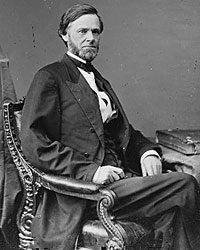

John Sherman took an active interest in military mobilization at the beginning of the Civil War – even serving as a military aide to General Robert Patterson and personally raising two regiments in Ohio. Sherman and his brother William T. Sherman had a close and supportive relationship, but unlike his brother, John Sherman was a committed abolitionist. He was also more temperate and reserved than his tempestuous brother, who had left the Army years before the Civil War. The differences between the two men were illustrated when Senator Sherman took his brother to the White House in the spring of 1861. As William T. Sherman recalled in his memoirs, the meeting was a disaster:

One day, John Sherman took me with him to see Mr. Lincoln. He walked into the room where the secretary to the President now sits, we found the room full of people, and Mr. Lincoln sat at the end of the table, talking with three or four gentlemen, who soon left. John walked up, shook hands, and took a chair near him, holding in his hand some papers referring to, minor appointments in the State of Ohio, which formed the subject of conversation. Mr. Lincoln took the papers, said he would refer them to the proper heads of departments, and would be glad to make the appointments asked for, if not already promised. John then turned to me, and said, “Mr. President, this is my brother, Colonel Sherman, who is just up from Louisiana, he may give you some information you want.” “Ah!” said Mr. Lincoln, “how are they getting along down there?” I said, “They think they are getting along swimmingly-they are preparing for war.” “Oh, well!” said he, “I guess we’ll manage to keep house.” I was silenced, said no more to him, and we soon left. I was sadly disappointed, and remember that I broke out on John, d-ning the politicians generally, saying, “You have got things in a hell of a fig, and you may get them out as you best can,” adding that the country was sleeping on a volcano that might burst forth at any minute, but that I was going to St. Louis to take care of my family, and would have no more to do with it. John begged me to be more patient, but I said I would not; that I had no time to wait, that I was off for St. Louis; and off I went.1

Senator Sherman himself admitted of his brother: “Cump is like a fine machine with every screw one half turn loose.” Nevertheless, Senator Sherman supported his brother’s career as a Civil War officer – and General Sherman reciprocated the support. General Sherman warned his brother in December 1862 not to get involved in controversies over military leadership: “The President [is] charged with this, has the right and ought to regulate all matters of command….[General George B.] McClellan will be recalled sooner or later – But leave that to the President.”2

A month later, General Sherman advised his brother: “You lay low – don’t commit yourself too Soon – Let things foment. The early actors & heroes of this war will be swept away, and those who study its progress, its developments and divine its course and destiny will be most appreciated – We are in for the war and must fight it out, cost what it may. As to making popularity out of it, it is simply ridiculous and all who attempt it will be swept as chaff before the wind. If you see Mr. Lincoln tell him I appreciate the reproof of ordering [General John] McClernand to command me, and that I will count it an honor when he says he can spare my services.”3

Senator Sherman played an important role in the Cabinet confrontation of December 1862. As Maine Senator William Fessenden later recalled of the second Senate Caucus concerning the Lincoln Cabinet, Sherman objected to a substitute motion submitted by New York Senator Ira Harris because it “might be construed as an expression of opinion that all the members of the Cabinet should go out. He pressured this was not desired. No one wished Mr. Chase to leave the Treasury, which he had managed so ably, Mr. Sherman further said that he doubted whether changing the Cabinet would remedy the evil. The difficulty was with the President himself. He had neither dignity, order, nor firmness. His (Mr. Sherman’s) course would be to go directly to the president, and tell him his defects. It was doubtful if even that would do any good.”4

As he had in the House, John Sherman in the Senate took a leading role on financial matters. He shepherded the national banking bill through to passage for Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase.

Senator Sherman saw the banking legislation as vital to the preservation of the Union: “The establishment of a national currency, and of this system, as the best that has been yet devised, appears to me all important. It is more important than the loss of a battle. In comparison with this, the fate of three million negroes held as slaves in the southern States is utterly insignificant.”sup>5

Sherman’s political style did not always win him friends. Historian Jon Schaff wrote: “Sherman’s constant defense of Chase and the administration eventually offended some turf conscious congressmen. Jacob Collamer (R-VT) castigated Sherman for insinuating that Senators should support the bank bill simply because the administration desired it.”6

Sherman’s relations with President Lincoln were also rocky. Historian Marc Egnal wrote that the war made the anti-slavery Sherman into an abolitionist – albeit an advocate of gradual emancipation: “Sherman favored gradual rather than immediate emancipation, particularly when the slaves belong to loyal masters in the border states.”7 Like many other Ohio Republicans, he preferred the strong anti-slavery positions of Secretary of the Treasury Chase. Historian Stewart Mitchell noted that “movement to replace [Lincoln] with his secretary of the treasury became menacing. Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy of Kansas, and [Ohio Senator] John Sherman aided and abetted the ambitious Chase until such time as the action of the legislature of Ohio made it obvious that the secretary could not bring even his own state again Lincoln. The drive for a change of leaders in 1865 had the secret support of three-quarters of the Republicans in the Senate of the United States at one time, but bitterness and double-dealing proved a boomerang. The conspirators outdid themselves, and public opinion began to take notice.”8 Chase biographer John Niven wrote that “John Sherman’s ill-conceived, ill-timed, and scurrilous public attack on Lincoln backfired on the Chase candidacy.”9

Journalist John W. Forney often acted as a political emissary for President Lincoln. After Senator Sherman endorsed the Chase presidential candidacy in March 1864, Forney wrote Mr. Lincoln: “I had a long and very interesting interview with Hon. John Sherman, last night, and I think it is my duty to inform you that he freely admits the certainty of your renomination, and is evidently desirous of being put in kind relations with you. He would like to have a confidential interview at such time as you may fix, and I think it would be well for you to send for him. Mr. Sherman is an important man, and is anxious to make some statements to you which I think you should hear. I may add that the fact that I write to you is not unknown to him, and I will therefore beg of you to send me an answer, that I may communicate your wishes to him.10

Sherman felt sufficiently comfortable with President Lincoln to lobby strongly for Chase’s appointment to succeed Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in the fall of 1865. Sherman wrote the President that “Chase will reflect higher honor in the exalted position of Chief Justice than Judge [Noah] Swayne & his appointment could be justified by obvious political reasons.”11

Relations continued to improve in 1865 – in part because General Sherman steadily rose in the estimation of President Lincoln. At the end of March 1865, General Sherman reunited with President Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia to discuss military strategy to conclude the war. Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote: “On the swift armed steamer the Bat Sherman started down the James River that afternoon, pacing the deck with his brother John Sherman of the Buckeye State. A knowing scribe was to write of the two brothers and how dramatically time had reversed their characters. ‘John, once the wild, bad boy of the Sherman family, was now watchdog of the nation’s finance, chairman of the Senate committee on expenditures, a man already cold from the handling of money, public and private. Cump (the family nick-name for William Tecumseh), the shy, gentle boy, had become a man whose name symbolized devastation.’ To the shut-mouthed Senator the General confided some of Lincoln’s ideas and feelings spoken in the morning, the Senator writing later, ‘I did not at the time agree with the generous policy proposed by Mr. Lincoln.'”12

In 1881, John Sherman wrote: “Mr Lincoln possessed all the qualities required to inspire confidence and to unite all the loyal elements of our much-divided people in the great conflict of our civil war, when the possibility of Republican institutions,, in a wide extended country, was on trial. At first I thought him slow, but he was fast enough to be abreast with the body of his countrymen, and his heart beat steadily and hopefully with them.”13

In addition to practicing law in Ohio, John Sherman was involved in lumber and real estate there. He lost an 1859 bid for Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives because of his association with a controversial anti-slavery book. Later, he served as Secretary of the Treasury (1877-81) and briefly as Secretary of State (1897-98). He was known for his financial expertise and authoring Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Sherman was less successful in an 1880 attempt to win the Republican presidential nomination. It went instead to his campaign manager, James Garfield. Garfield won the election but was assassinated at the Washington railway station – with Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln nearby.

Footnotes

- William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, pp. 167-168.

- Letters of William T. Sherman, December 20, 1862, p. 348 (Letter from William T. Sherman to John Sherman).

- Letters of William T. Sherman, p. 375 (Letter from William T. Sherman to John Sherman, January 25, 1863).

- Francis Fessenden, Life and Public Services of William Pitt Fessenden, p. 237.

- Marc Egnal, “Leader of the Second American Revolution,” Ohio History, Volume 14, 2007, p. 108.

- Jon Schaff , “The Domestic Lincoln: White House Lobbying of the Civil War Congresses,” White House Studies, Winter 2002.

- Egnal, “Leader of the Second American Revolution,” Ohio History, Volume 14, 2007, p. 107.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 360-361.

- John Niven, “Lincoln and Chase: A Reappraisal,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 1991.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from John W. Forney to Abraham Lincoln, March 5, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from John Sherman to Abraham Lincoln, October 22, 1864).

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 161.

- Osborn H. Oldroyd, editor, The Lincoln Memorial: Album-Immortelles, p. 428.

Visit

Salmon P. Chase

William T. Sherman

Abraham Lincoln and Ohio

Abraham Lincoln and Civil War Finance