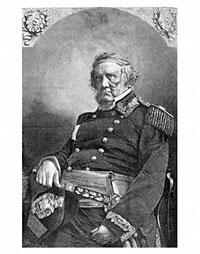

Nicknamed “Old Fuss & Feathers,” Union Army General Winfield Scott was the Army Chief from 1841-1861 and formulated the far-sighted “Anaconda Plan” at the beginning of the Civil War. His first mission for Mr. Lincoln was to secure the nation’s capital for the incoming administration and the safety of President Lincoln’s inauguration. He carried on communications with Mr. Lincoln through emissaries such as Illinois Congressman Elihu Washburne. When his show of military force successfully prevented any interference with the inaugural ceremonies at the Capitol on March 4, Scott told Thurlow Weed: “It is a success. God be praised! God in His goodness be praised!”1

Scott had reason to rejoice. Scott biographer Charles Winslow Elliott wrote: “On the night of the 3d word was brought to headquarters that an attempt would be made to blow up the platform on which Lincoln would take his oath of office and deliver his inaugural. Before daylight Colonel [Charles] Stone had a trustworthy battalion of militia drawn up across the foot of the stairway; soldiers were on guard beneath the stands, and no one was permitted to approach from without. The program of the day was followed without the slightest interruption of interference. Unable to mount a horse, the General-in-Chief, seated in his coupé, paralleled the progress of the Presidential equipage on F Street, and throughout the ceremony at the Capitol remained in a strategic position at a corner near the grounds, watchfully waiting and ready at a moment’s notice to direct the instant suppression of any hostile demonstration. His firm grasp of the situation was apparent from the departure of the carriage occupied by Lincoln and Buchanan from Willard’s until the peaceful completion of the ceremony. The battery, whose guns dominated the plateau before the east front, was in fact called upon to fire; but their thunders were in salute only, announcing to the city and the nation that Abraham Lincoln was President of the United States.”2

Historian Walter A. McDougall described Scott during his service in the Mexican-American War as “vain, ambitious, and a stickler for rank, rules, and spit and polish – hence his nickname ‘Old Fuss and Feathers.”3 Scott, according to historian Russell McClintock was “a brilliant military commander and insufferable political busybody.”4 McClintock wrote that before Lincoln’s inauguration: “Winfield Scott became a rallying point for antisecession sentiment, his seemingly bold and manly stance contrasting sharply with Buchanan’s weak vacillation.”5

But as the Lincoln Administration took office, Scott also vacillated. Historian John Eisenhower noted that the kind of conflicting advice Mr. Lincoln was receiving was reflected in a letter Scott sent Seward shortly before the inauguration:

“Hoping that, in a day or two, the new President will have, happily, passed through all personal dangers, & find himself installed an honored successor of the great Washington — with you as chief of his cabinet — I beg leave to repeat, in writing, what I have before said to you, orally, this supplement to my printed “views,” (dated October last) on the highly disordered condition of our (so late) happy & glorious union. To meet the extraordinary exigencies of the times, it seems to me that I am guilty of no arrogance in limiting the President’s field of selection to one of the four plans of procedure, subjoined: –

I. Throw off the old, & assume a new designation — the Union party; — adopt the conciliatory measures proposed by Mr. Crittenden, or the Peace convention, & my life upon it, we shall have no new case of secession, but, on the contrary, an early return of many, if not a;l the states which have already broken off from the Union, without some equally benign measure, the remaining slave holding states will, probably, join the Montgomery confederacy in less than sixty days, when this city — being included in a foreign country — would require permanent Garrison of at least 35,000 troops to protect the Government within it.

II. Collect the duties on foreign goods outside the ports of which this Government has lost the command, or close such ports by acts of congress, & blockade them.

III. Conquer the seceded States by invading Armies. No doubt this might be done in two or three years by a young able General — a Wolfe, a Desaix or a Hoche, with 300,000 disciplined men — estimating a third for Garrisons, & the loss of a yet greater number by skirmishes, sieges, battles & southern fevers. The destruction of life and property, on the other side, would be frightful — however perfect the moral discipline of the invaders.

The conquest completed at that enormous waste of human life, to the north and north west — with at least $250[,]000,000, added thereto, and cui bono? — Fifteen devastated provinces — not to be brought into harmony with their conquerors; but to be held, for generations, by heavy garrisons — at an expense quadruple the net duties or taxes which it would be possible to extract from them — followed by a Protector or an emperor.

IV. Say to the seceded — States — wayward sisters, depart in peace!”6

Scott’s opposition to supplying Fort Sumter in March 1861 was probably encouraged by his friend, William Seward. Always ambitious and vain, his organizational ideas were inadequate for the massive Army buildup of 1861 and General George McClellan, his nominal subordinate, circumvented him to Scott’s immense irritation. A diary notation by Gideon Welles illustrates the problems that Scott had in organizing the rapidly growing army in the spring of 1861:

I well remember an interview between these two officers the period that letter was written, the President, myself, and two or three others being present. It was in General Scott’s rooms opposite the War Office. In the course of conversation, which related to military operations, a question arose as to the number of troops there were in and about Washington. Cameron could not answer the question; McClellan did not; General Scott said no reports were made to him; the President was disturbed. At this moment [Seward] stated the several commands,—how many regiments had reported in a few days, and the aggregate at the time of the whole force. The statement was made from a small paper, and appealing to McClellan, that officer replied that the statement approximated the truth. General Scott’s countenance showed great displeasure. ‘This,’ said the veteran warrior, ‘is a remarkable state of things. I am in command of the armies of the United States, but have been wholly unable to get any reports, any statement of the actual forces, but here is the Secretary of State, a civilian, for whom I have great respect for who is not a military man nor conversant with military affairs, though his abilities are great, but this civilian is possessed of facts which are withheld from me. Military reports are made, not to these Headquarters but to the State Department. Am I, Mr. President, to apply to the Secretary of State for the necessary military information to discharge my duties?’7

Scott was not physically in condition to oversee Union War efforts. His age and weight made it difficult for him to stand and walk, much less review troops in the field. After one cabinet meeting, Mr. Lincoln, Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Secretary of State William Seward went to the building where Scott maintained his home and office. According to John Usher, who was later secretary of the interior:

….one bleak rain day they went over to his quarters. General Scott was so infirm that he could not come to the White House, or remain in the war department and he had taken a room for his quarters across the street, near the war department. When they went in he had a stick or two upon the first burning brightly, and they all took seats around the fire. General Scott was lying on a low and broad lounge in one corner of the room. He had a strap attacked to a ring in the ceiling, and another ring at the end, reaching down over him a little below his breast, which he was accustomed to take hold of and pull himself up with, for he was very large and plethoric. After they sat down he got hold of that ring, with some trouble pulled himself to an upright position and swung his feet off the lounge upon the floor. Before they said anything they sat there looking at him, and he commenced his speech to the President.

‘I am an old man,’ he said. ‘I have served my country faithfully I think, during a long life. I have been in two great wars and fought them through, and now another great war is on and I am nominally at the head of the army, but I don’t know how many men are in the field, where they are, how they are armed and equipped or what they are capable of doing or what reasonably ought to be expected of them. Nobody comes to tell me and I am in ignorance about it, and can form no opinion respecting it. I think under all the circumstances I had better be relieved from further service to my country.”8

President Lincoln was out for a carriage ride when word was received that the Union Army had been defeated at a battle near Manassas on July 21, 1861. When he received news, he went immediately to Scott’s residence. Scott assumed responsibility for the Union defeat at Bull Run—but in a way that implied he had been forced to order the attack by President Lincoln. Soon thereafter, George McClellan was appointed head of the Army of the Potomac and he began a persistent campaign to undermine Scott’s authority. By November 1861, old, fat, and feeble, Scott retired to West Point, but he remained an occasional advisor of President Lincoln. In his Annual Message to Congress a month after Scott’s departure, President Lincoln wrote: “Since your last adjournment, Lieutenant General Scott has retired from the head of the army. During his long life, the nation has not been unmindful of his merit; yet, on calling to mind how faithfully, ably and brilliantly he has served the country, from a time far back in our history, when few of the now living had been born, and thenceforward continually, I cannot but think we are still his debtors, I submit, therefore, for your consideration, what further mark of recognition is due to him, and to ourselves, as a grateful people.”9

In June 1862, Mr. Lincoln left Washington suddenly to visit General Scott. According to presidential aide John G. Nicolay, “the President’s sudden visit to West Point, which set a thousand rumors to buzzing, as if a beehive had been overturned. There was all sorts of guessing as to what would result—the Cabinet was to break up and be reformed—Generals were to be removed and new war movements were to be organized. You have no idea how rapidly rumors are originated and spread here, nor how [much] importance even the coolest and most discriminating of our people attach to them, notwithstanding the fact that they are daily served with the most extraordinary Munchausens. My own impression is that the President merely desired and went to hold a conference with Gen. Scott about military matters and that no immediate avalanches or earthquakes are to be produced thereby…”10

At the end of the war, Scott asked the President to pardon his grand nephew, a Confederate soldier, and Mr. Lincoln did so.

Scott was a hero both of the War of 1812 for actions on Canadian front and the Mexican-American War for leading an expedition to Mexico City. Well-traveled and well-connected, he knew everyone through his long career in the Army at stations in Washington and New York. He was skillful at resolving political-military disputes and at embroiling himself in military personnel feuds. He had long had political ambitions and was the unsuccessful Whig candidate for President in 1852—the last serious presidential candidate of the Whig Party.

Footnotes

- Glyndon G. Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 270.

- Charles Winslow Elliott, Winfield Scott: The Soldier and the Man, pp. 695-696

- Walter A. McDougall, Throes of Democracy: The American Civil War Era, 1829-1877, p. 234.

- Russell McClintock, Lincoln and the Decision for War: The Northern Response to Secession, p. 64.

- McClintock, Lincoln and the Decision for War: The Northern Response to Secession, p. 87.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Winfield Scott to William H. Seward, March 3, 1861)

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 241.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, pp. 382-383.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume V, p.50 (First Annual Message of President Lincoln , December 3, 1861).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 82.

Visit

The War Department

The Winder Building Annex

George B. McClellan

Simon Cameron

Irvin McDowell

John Palmer Usher

John G. Nicolay

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Visit to West Point (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief