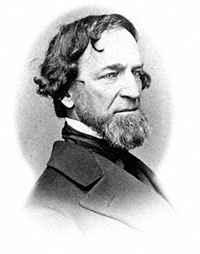

Congressman from Illinois (Republican, 1861-65), abolitionist, and strong Lincoln loyalist in the House of Representatives, Isaac N. Arnold was a state legislator who shifted from Democratic to Free Soil to Republican Parties and helped form the Illinois Republican Party. Arnold was a one-time schoolteacher and Chicago attorney served in the Union Army at the same time he was in Congress.

Like many Illinois Republican congressmen, he had special access to Mr. Lincoln. In June 1863, he helped convince President Lincoln to revoke General Ambrose Burnside’s order closing the Chicago Times. On January 1, 1864, he paid a New Years Day call on Mr. Lincoln. “After congratulating the President on the great victories which had been achieved in the East and the West, and the brightening prospects of peace, [Arnold] said:

‘I hope, Mr. President that on next New Year’s day I have the pleasure of congratulating you on three events which now seem very probable.”

“What are they?” said he.

“First, That the war may be ended by the complete triumph of the Union forces.

“Second, That slavery may be abolished and prohibited throughout the Union by an amendment of the Constitution.

“Third, That Abraham Lincoln may have been re-elected President.”

“I think,” replied he, with a smile, “I think my friend, I would be willing to accept the first two by way of compromise.”1

But the exchanges between the two were not always so amicable. Arnold pushed President Lincoln in May 1863 to dismiss General-in-Chief Henry Halleck. The President replied sharply: ‘I am compelled to take more practical and unprejudiced view of things. Without claiming to be your superior, which I do not my position enables me to understand my duty in all these matters better than you possibly can, and I hope you do not yet doubt my integrity.'”2

In a letter to President Lincoln after the Battle of Chancellorsville and before the Battle of Gettysburg, , Arnold suggested that Halleck be replaced — and blamed him for the status of General Benjamin Butler, John C Fremont, & Franz Sigel. Mr. Lincoln’s response reflects their close personal relationship. Atypically, Mr. Lincoln signed the letter “Your friend, as ever.”

Your letter advising me to dismiss Gen. Halleck is received. If the public believe, as you say, that he has driven Fremont, Butler, and Sigel from the service, they believe what I know to be false; so that if I were to yield to it, it would only be to instantly beset by some other demand based on another falsehood equally gross. You know yourself that Fremont was relieved at his own request, before Halleck could have had any thing to do with it–went out near the end of June, while Halleck only cam in near the end of July, I know equally well that no wish of Halleck’s had any thing to do with the removal of Butler or Sigel. Sigel, like Fremont, was relieved at his own request, pressed upon me almost constantly for six months, and upon complaints that could have been made as justly by almost constantly for six months, and upon complaints that could have been made as justly by almost any corps commander in the army, and more justly by some. So much for the way they got out. Now a word as to their not getting back. In the early Spring, Gen. Fremont sought active service again; and, as it seemed to me, sought it in a very good, and reasonable spirit. But he hold the highest rank in the Army, except McClellan, so that I could not well offer him a subordinate command. Was I to displace Hooker, or Hunter, or Rosecrans, or Grant, or Banks? If not, what as I to do? And similar to this, is the case of both the others. One month after Gen. Butler’s return, I offered him a position in which I thought and still think, he could have done himself the highest credit, and the country the greatest service, but he declined it. When Gen. Sigel was relieved, at his own request as I have said, of course I had to put another in command of his corps. Can I instantly thrust that other out to put him in again?

And now my good friend, let me turn your eyes upon another point. Whether Gen. Grant shall or shall not consummate the capture of Vicksburg, his campaign from the beginning of this month up to the twenty second day of it, is one of the most brilliant in the world. His corps commanders, & Division commanders, in part, are McClernand, McPherson, Sherman, Steele, Hovey, Blair & Logan. And yet taking Gen. Grant & these seven of his generals, and you can scarcely name one of them that has not been constantly denounced and opposed by the same men who are now so anxiously to get Halleck out, and Fremont & Butler & Sigel in. I believe no one of them went through the Senate easily, and certainly one failed to get through at all. I am compelled to take a more impartial and unprejudiced view of things. Without claiming to be your superior, which I do not, my position enables me to understand my duty in all these matters better than you possibly can, and I hope do not yet doubt my integrity.3

Lincoln was a steadfast friend to Arnold. Arnold was equally steadfast in his support of Lincoln’s reelection, delivering a speech in the House: “Reconstruction: Liberty the cornerstone and Lincoln the architect” which was subsequently distributed as a campaign pamphlet. His theme, noted Rawley, was “Nobody but Lincoln.”4

Arnold declined to run for re-election in 1864 after a conflict within the Republican Party developed over the Chicago congressional nomination. He was under consideration for appointment as Secretary of the Interior in the second Lincoln administration, but the appointment instead went to Senator James Harlan of Iowa. Arnold was the last person to see the President before he left for Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865. Arnold later wrote a book and a pamphlet about Mr. Lincoln, in which he commented on his amazing memory: “As an illustration of the power of his memory, I recollect to have once called at the White House, late in his Presidency, and introducing to him a Swede and a Norwegian. He immediately repeated a poem of eight or ten verses, describing Scandinavian scenery and old Norse legends. In reply to the expression of their delight, he said that he had read and admired the poem several years before, and it had entirely gone from him, but seeing them recalled it.”5

One contemporary said of the Chicago congressman: “As we all knew him, Mr. Arnold was a man of great independence of character, thought, and action. Making up his mind as to what was right, he always acted up to his convictions. He never pandered to low tastes or popular prejudices. There was not the slightest tinge of the demagogue in all his composition.”6

Arnold was a vigorous speaker. He was defeated in February 1860 for the Republican nomination for mayor of Chicago. He instead was elected to Congress.

Arnold took a job as auditor of the Treasury Department, but resigned in 1866 in a political dispute with Andrew Johnson. The longtime president of the Chicago Historical Society, he wrote an early biography of Mr. Lincoln, History of Abraham Lincoln and the Overthrow of Slavery. A revision two decades later was called The Life of Abraham Lincoln. Arnold served reluctantly as the counsel for Mary Todd Lincoln in her insanity hearing and again as counsel when she was released.

Footnotes

- Isaac Arnold, Life of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 351-352.

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, pp. 406-407.

- Roy P.Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, pp. 230-231.

- James A. Rawley, Isaac Newton Arnold, Lincoln’s Friend and Biographer,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Winter 1998, p. 49.

- Harold Holzer, editor, Lincoln as I Knew Him, p. 47.

- Edward Gay Mason, editor, Early Chicago and Illinois, p. 33.

Visit

Owen Lovejoy

Ambrose E. Burnside

James Harlan

Henry W. Halleck

Isaac N. Arnold (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Chicago