The employee fixture at the door through the previous four administrations was “Old Edward Moran.” He was there when President Lincoln first came to the White House and he continued to amuse the President:

He is intensely absorbed in something, and it is best to take the portfolio and follow him in silence. When he reaches the front door, and opens it and looks out, he discovers that a drizzle of rain is falling. The old doorkeeper is standing by, rubbing his hands as usual, and with his perpetual half smile of suppressed humor flickering across his face.

‘Edward,’ says Mr. Lincoln, go up to my room and bring me my umbrella. It stands in the corner, behind my table.’

Edward is gone, but a moment, while Mr. Lincoln stands peering gloomily out into the darkness, and now he is back again, but he brings no umbrella.

‘Your Excellency,’ he remarks, washing his hands diligently, ‘it’s not there. I think the owner must have come for it. I’ll get another – just a minute, sir.’1

At the beginning of President Lincoln’s term in office, the doors of the White House were guarded in a haphazard manner. As a result, the interior of the White was constantly threatened by vandalism from Americans interested in taking home a piece of the Executive Mansion. The lack of security was reflected by the inventors of military gadgets who were frequent callers the President. One such inventor observed: “On my arrival at the White House, I was ushered immediately into the reception room, with my repeating rifle in my hand, there I found the President alone.”2 At the beginning of the Civil War, there were only six pistols available for guards assigned to the executive mansion. When Prince Napoleon visited the White House on August 3, 1861, he found no one to greet his party at the door. His aide complained: “A palace where the owners or the tenants fulfill the duties of a doorman is quite ridiculous anywhere indeed, even in America. It is a double ostentation: an ostentation of wealth and an ostentation of austerity. I like neither.”3

Sometimes, people never got to the office — encountering the President instead on the portico. One such man came across the President just outside the White House door: “The Lord is with you, Mr. President,” said the visitor. “And the people too, sir; and the people, too!”4 Journalist Noah Brooks recalled: “Going out of the main-door of the White House one morning, he met an old lady who was pulling vigorously at the door-bell, and asked her what she wanted. She said that she wanted to se ‘Abraham the Second.’ The President, amused, asked who Abraham the First might be, if there was a second? The old lady replied, ‘Why, Lor’ bless you! We read about the first Abraham in the bible, and Abraham the Second is our President.’ She was told that the President was not in his office then, and when she asked where he was, she was told, ‘Here he is!’ Nearly petrified with surprise, the old lady managed to tell her errand, and was told to come next morning at nine o’clock, when she was received and kindly cared for by the President.”5

Sometimes, visitors might first encounter the Lincoln’s youngest son, Tad. “He invested, one morning, all his pocket money in buying the stock in trade of an old woman who sold gingerbread near the Trasury. He made the Government carpenters give him a board and some trestles, which he set up in the posing porte-cochere of the White House, and on this rude counter displayed his wares, Every office-seeker who entered the hosue that morning brought a toothsome luncheon of the keen little merchant, and when an hour after the opening of the booth a member of the household discovered the young pastryman the admired center of a group of grinning servants and toadies, he had filled his pockets and his hat with currency, the spoil of the American public. The juvenile operator made lively work of his ill-gotten gains,, however, and before night was penniless again.”6

Colonel Charles Halpine, an aide to General Henry Halleck, observed: “The entrance-doors, and all doors on the official side of the building, were open at all hours of the day, and very late into the evening; and I have many times entered the mansion, and walked up to the rooms of the two private secretaries, as late as nine or ten o’clock at night, without seeing or being challenged by a single soul. There were, indeed, two attendants, — one for the outer door, and the other for the door of the official chamber; but these — thinking, I suppose that none would call after office hours save persons who were personally acquainted, or had the right of official entry — were, not unfrequently, somewhat remiss in their duties.” 7 Doorkeeper Thomas Pendel recalled:

Almost every day about ten o’clock I would accompany Mr. Lincoln to the War Department. I used to try to expedite his leaving the White House as much as possible, because people would always hang around and wait to see Mr. Lincoln and would thrust notes into his hands as he passed and in many ways annoy him. One day just as we got to the front door, after going out of the private corridor, there was a nurse who had been in the East Room with an infant in her arms and a little tot walking by her side. Just as we were about to pass out of the door, she got in front of us. I took hold of the little tot gently, and moved her to one side so that we could get out. The President noticed this action, and rather disapproved of my moving the child to let him pass and said, ‘That’s all right; that’s all right’. The interpretation I put upon his words was that he would sooner have been annoyed by people thrusting letters into his hands than make a little child move aside for him to pass.8

Those entering the White House for the President’s semiweekly receptions came through the main entrance. On one occasion, according to army Sergeant Smith Stimmel, several members of the presidential bodyguard decided to “slick up” and attend a reception. “We stood in the anteroom quite a while watching the dignitaries pass in before we could make up our minds to venture into the presence of the President,” wrote Stimmel later. “The Cabinet Ministers, the Judges of the Supreme Court, Senators and Congressmen, foreign Ambassadors in their dazzling uniforms, all accompanied by their wives, Army and Navy officers of high rank, and the wealth and aristocracy of the city, all in full evening dress, were there. Naturally we boys in the garb of the common soldier felt a little timid in the presence of such an assemblage. We stood talking for a while with the doorkeeper, whom we had come to know. When one of the boys expressed some reluctance about going in, the doorkeeper said, ‘Go on in; he would sooner see you boys than all the rest of these people.’”9

On the last day of President Lincoln’s life — April 14, 1865 — he went for a carriage drive with his wife Mary. “It was late in the afternoon when he returned from his drive, and as he left his carriage he saw going across the lawn toward the Treasury a group of friends, among them Richard Oglesby, then Governor of Illinois. ‘Come back, boys, come back,’ he shouted. The party turned, joined the President on the portico, and went up to his office with him,” wrote biographer Ida Tarbell. “‘How long we remained there I do not remember,’ says Governor Oglesby. ‘Lincoln got to reading some humorous book; I think it was by ‘John Phoenix.’ They kept sending for him to come to dinner. He promised each time to go, but would continue reading the book. Finally he got a sort of peremptory order that he must come to dinner at once. It was explained to me by the old man at the door that they were going to have dinner and then go to the theater.’” 10

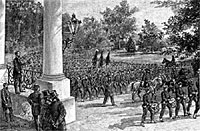

Near the portico, President Lincoln frequently reviewed troops who either recently had joined the Union Army or who were completing their tours of duty. Journalist Ben Perley Poore wrote that “by the middle of August, 1862, they were pouring into Washington at the rate of a brigade a day. The regiments, on their arrival, were marched past the White House, singing, ‘We are coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand more.’ And ‘Father Abraham’ often kindled their highest enthusiasm by coming to the front entrance and in person reviewing the passing hosts.”11 He greeted the 42nd Massachusetts Regiment on October 31, 1864: “You have completed a term of service in the cause of your country, and on behalf of the nation and myself I thank you. You are going home; I hope you will find all your friends well. I never see a Massachusetts regiment but it reminds me of the difficulty a regiment from that State met with on its passage through Baltimore; but the world has moved since then, and I congratulate you upon having a better time to-day in Baltimore than that regiment had. To-night, midnight, slavery ceases in Maryland, and this state of things in Maryland is due greatly to the soldiers. Again I thank you for the services you have rendered the country.”12

Early in the war, President Lincoln came down to the portico entrance to visit with Winfield Scott and spared the nearly invalid general the White House stairs. One night in February 1862, William O. Stoddard returned with the President from a visit to Secretary of State William H. Seward’s House. Old Edward met them at the door and gravely informed Mr. Lincoln: “The doctor has been here, sir…..The Madam would like to see you right away, sir. Soon as you come in.” The President immediately climbed the private staircase to the second floor. Old Edward admitted to Stoddard that he thought Willie was very sick, but Mrs. Lincoln “told me not to alarm the President.” 13

President Lincoln also used this entrance when he went for a drive or spent the evening at the Soldiers Home in north Washington. Soldier Thomas Hopkins encountered him there:

After fourteen months at the front, I was sent to a hospital in Washington. The next time I saw Mr. Lincoln was on the steps of the White House, one evening late in 1863. Mr. Lincoln came out of the front entrance and entered a carriage to be driven to his summer cottage at the Solders’ Home outside of the city. This was a close-range view.

My father, in eating an apple, had the rather unusual habit of holding it in both hands. Mr. Lincoln, as he stepped out on the portico of the White House, was eating an apple which he was holding in both hands! He had on the inevitable high hat, which he wore summer and winter. Still eating the apple, he passed down the steps, bowing and smiling, and entered the closed carriage. He had to bend his tall body very much before he could enter.

The thing that I remember best and care most to remember was the smile that flitted across Mr. Lincoln’s plain and rugged face. It was not forced. It was as spontaneous as the smile of a mother looking down into the face of the child in her arms….But there was nothing about him that was imposing or awesome; no exhibition of the pride or arrogance, or even the reserve, that sometimes characterizes the attitudes of rulers of great nations. The world now knows that he loved not himself but his fellow man. My boy’s heart warmed toward him, and I longed to hear him speak. 14

Outside this entrance, Washingtonians often gathered at important moments in the War to “serenade” the President. Here they gathered during the last week of the war in April 1865 to hear President Lincoln’s reactions to victory and ideas about reconstruction. On November 11, 1864, journalist Noah Brooks reported how the President responded to his reelection.

“Last night an impromptu procession, gay with banners and respondent with lanterns and transparencies, marched up to the White House, the vast crowd surging around the great entrance, block up all of the semicircular avenue thereto as far as the eye could reach. Bands brayed martial music on the air, enthusiastic sovereigns cheered to the echo, and the roar of cannon shook the sky, even to the breaking of the President’s windows, greatly to the delight of the crowd and Master ‘Tad’ Lincoln, who was flying about window to window, arranging a small illumination on his own private account. The President had written out his speech, being well aware that the importance of the occasion would give it significance, and he was not willing to run the risk of being betrayed by the excitement of the occasion into saying anything which would make him sorry when he saw it in print. His appearance at the window was the signal for a tremendous yell, and it was some time before the deafening cheers would permit him to proceed….” 15

Footnotes

- William Stoddard,Inside the White House in War Times, p. 24.

- Robert V. Bruce,Lincoln and the Tools of War, p. 142.

- Camille Ferri Pisani,Prince Napoleon in America, 1861, p. 95.

- Francis Carpenter,Six Months at the White House, p. 36.

- Michael Burlingame, editor,Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 207.

- Michael Burlingame, editor,At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, pp. 112-113.

- Carpenter, pp. 65-66.

- Thomas Pendel,Thirty Six Years at the White House, p. 16.

- Smith Stimmel,Personal Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 45-46.

- Ida Tarbell,Life of Lincoln, Volume II, p. 235.

- Ben Perley Poore,Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, p. 130

- Roy P. Basler, editor,Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 84.

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor,Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 146.

- From Thomas S. Hopkins, “A Boy’s Recollections of Mr. Lincoln”,St. Nicholas, May 1922 in Rufus Wilson,Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 486.

- Michael Burlingame, editor,Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 145.

Visit