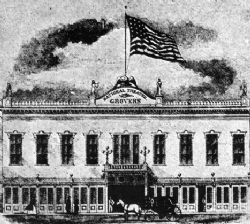

Grover’s on E Street between 13th and 14th Streets was one of two theaters favored by President and Mrs. Lincoln for small theater parties. They made scores of visits to Grover’s. “The proprietors of Grover’s Theatre fitted up a handsome and commodious box for his especial use,” wrote Lincoln aide William O. Stoddard.1 Mrs. Lincoln particularly loved the German and Italian opera groups that played here. John W. Forney, however maintained that though Mr. Lincoln “frequently accompanied Mrs. Lincoln to the opera, it was rather in obedience to a social demand or an eagerness for rest in the corner of his box than a taste for scientific music.”2

On one trip the Lincolns made to the theater with Congressman Schuyler Colfax in late 1862, owner Leonard Grover saved President Lincoln from an unpleasant incident. According to Historian Margaret Leech, “Grover’s was in a neighborhood of saloons and disorderly houses, frequented by secessionist roughs whose antipathy to the administration had been increased by the Emancipation Proclamation. A jeering crowd gathered around the President’s carriage. The coachman, Grover said, was drunk, and fell sprawling on the sidewalk, as Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln entered the carriage. The crowd gave a threatening shout. There was only a one-armed drummer boy on the box, and Grover was frightened. He sprang to the box himself, took up the reins, and drove to Colfax’s residence and then to the White House. Both the President and Mrs. Lincoln warmly thanked him for a very great service.”3

Proprietor Leonard Grover recalled that one night Edwin Stanton came to the theater to discuss policy while the President watched the play. Finally, in an attempt to get his boss’s full attention, the Secretary of War “grasped Mr. Lincoln by the lapel of his coat, slowly pulled him round face to face, and continued the conversation. Mr. Lincoln responded to this brusque at with all the smiling geniality that one might bestow on a similar act from a favorite child, but soon again turned his eyes to the stage.’” Tacitly admitting defeat, Stanton “said good night, and withdrew.”4

Tad Lincoln and Bobby Grover were playmates, who enjoyed adventures at both the theater and the White House. Historian Catherine Clinton wrote: “Tad became friends with Grover’s son Bobby, several years younger, and the boys spent time trawling for goldfish in the White House ponds, and on other escapades.”5 Tad also occasionally participate in the on-stage entertainment at Grover’s. According to historian Ruth Painter Randall:

One incident was told by the comedian John T. Raymond, who took park in the play involved, a burlesque called Pocahontas. In those days, when the soldiers caught a pickpocket, they would placard him – ‘This is a pickpocket’–and make him walk along the streets of Washington to the tune of the ‘Rogue’s March.’ The play burlesqued such a scene. Tad had come with his father to see Pocahontas and went backstage as usual. The actor said he was a jolly little fellow; everybody liked him,’ and someone had the bright idea of dressing him in a very ragged outfit and sending him on the stage with a mob in one of the scenes. Mr. Lincoln, sitting unnoticed in his box, suddenly saw Tad and broke into a hearty laugh. He threw up his hands in a mock gesture of dismay and then let one hand drop over the side of the box. The audience, hitherto unaware of the President’s presence, recognized that long, bony hand, for ‘there was no hand in the world like Mr. Lincoln’s.’ They set up a shout for him and he had to come to the front of the box and make a bow. When Tad returned, his father threw his arms around him in delight. ‘The pleasure, the affection of the father was so intense, so spontaneous…it was glorious to see him.’6

In late February and early March, 1864, the President attended several Shakespeare plays at Grover’s Theater starring Edwin Booth, brother of John Wilkes Booth. On February 20, proprietor Leonard Grover urged the President to attend a special “performance of Shylock and Don Caesar de Bazin [sic] by Mr. Edwin Booth. Your favorable answer will be taken as a great Compliment to the artist…” On March 15, 1865 the Lincolns were accompanied to a performance of the Magic Flute at Grover’s Theater by General James Grant Wilson and Clara Harris (who was also present the night of President Lincoln’s assassination). Wilson recalled that Mr. Lincoln “sat in the rear of the box leaning his head against the partition paying no attention to the play and looking so worn and weary that it would not have been surprising had his soul and body separated that very night. When the curtain fell after the first act, turning to him, I said: ‘Mr. President you are not apparently interested in the play.’ ‘Oh, no, Colonel,’ he replied; ‘I have not come for the play, but for the rest. I am hounded to death by office-seekers, who pursue me early and late, and it is simply to get two or three hours’ relief that I am here.’ After a slight pause he added: ‘I wonder if we shall be tormented in heaven with them, as well as with bores and fools?’ He then closed his eyes and I turned to the ladies.”7

As Leonard Grover remembered Lincoln’s theater habits and his rival: “Mr Lincoln had reserved a box at my theatre that night [April 14, 1865] and it should be noted that up to that time he had never attended Mr. Ford’s Theater,” According to Grover, “John T. Ford was an amiable gentleman, whose political proclivities differed little from mine. He was a stanch member of the Union party, which elected to office as President of the Board of Aldermen, and acting Mayor of the City of Baltimore. Doubtless his personal sympathies were with his State and with that portion of the country in which he was born and reared.”8

On the night that President Lincoln was assassinated in 1865 at Ford’s Theater, his son Tad was watching “Aladdin! or His Wonderful Lamp’ at Grover’s Theater. During the performance, the shooting of his father was announced on stage and Tad was taken back to the White House by Alphonso Dunn, the White House doorkeeper who had accompanied him. “They killed papa dead!” Tad cried.9

James Tanner, a clerk in the War Department who had learned shorthand after he lost in his from a war injury, was attending the theater at Grover’s that night. Later that night, he took notes for Secretary of War Edwin Stanton at the Peterson House where Mr. Lincoln lay dying. As he later recorded the night’s event:

“Last Friday night, a friend invited me to attend the Theatre with him, which I did, I would have preferred the play at Ford’s Theatre where the President was shot, but my friend chose the play at Grover’s which was ‘Aladdin, or the wonderful lamp.’ While sitting there, witnessing the play, about ten o’clock, or rather a little after, the entrance door was thrown open, and a man exclaimed, ‘President Lincoln is assassinated in his private box at Ford’s. Turn out!’ Instantly all was excitement, and a terrible rush commenced, and some one cried out, ‘Sit down, it is a ruse of the pickpockets.’ The audience generally agreed to this, for most of them sat down, and the play went on; soon however a gentleman came out from behind the scenes, and informed us that the sad news was too true. We instantly dispersed.”10

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame Editor, Inside the White House in War Times: Memoirs and Report of Lincoln’s Secretary: William O. Stoddard, p. 191.

- John W. Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, p. 168.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 309.

- Leonard Grover, “Lincoln’s Interest in the Theater,” Century, 1909, pp. 944-946.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Lincoln’s Sons, p. 145.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, pp. 424-425.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 261.

- Catherine Clinton, Mrs. Lincoln: A Life, p. 231.

- Thomas F. Pendel, Thirty Years in the White House, p. 44.

- Howard H. Peckham, “James Tanner’s Account of Lincoln’s Death,” Lincoln Quarterly, p. 177.

Visit

Thomas D. Lincoln

Ford’s Theater

Schuyler Colfax

Edwin M. Stanton

Abraham Lincoln and Literature