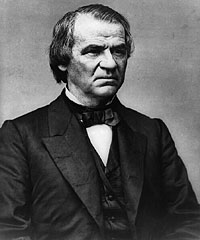

Andrew Johnson was the war Democrat who became Lincoln’s second vice presidential running mate in 1864 after being offered the Democratic vice presidential nomination by Stephen A. Douglas in 1860. Johnson supported John Breckinridge in the 1860 general election, but broke with Southern Democrats on the issue of secession in 1861 for which he was widely vilified in the South. A tailor by trade, he served as a state legislator (1836-37, 1842-43), Congressman (1843-53), Governor (1853-57) and Senator (1857-62). He served on the congressional Committee on the Conduct of War. He resigned from the Senate when he was appointed military governor of Tennessee by President Lincoln in early 1862.

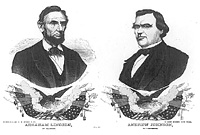

Johnson was selected as a logical War Democrat to place on the ticket of the Union presidential convention in Baltimore in 1864. Hannibal Hamlin’s replacement on the ticket came as a public surprise. There has always been a question about how much or whether President Lincoln intervened in Johnson’s selection. New York Republican Chauncey M. Depew, for one, recalled that in a meeting with fellow New Yorker Seward before the Convention, “Mr. Seward said that the situation demanded the nomination for vice-president of a representative from the border states, and whose loyalty had been demonstrated during the war…’You can quote me to the delegates, and they will believe I express the opinion of the President. While the president wishes to take no part in the nomination for vice-president, yet he favors Mr. Johnson.’”1

Johnson surprised Mr. Lincoln himself when he asked if his presence was necessary for the inauguration; “This Johnson is a queer man,” Mr. Lincoln told Shelby M. Cullom.2 The public was also surprised when a sick Johnson fortified himself with liquor in order to prepare for his swearing-in as Vice President on March 5, 1865. His subsequent speech in the Senate chamber was a strange humiliation of himself and everyone else present. “I am a-goin’ for to tell you here to-day; yes, I’m a-goin for to tell you all, that I’m a plebian! I glory in it; I am a plebian! The people—yes, the people of the United States have made me what I am; and I am a-goin’ for to tell you here to-day—yes, to-day, in this place—that the people are everything.”

Afterward, according to Senate aide John W. Forney, “Johnson was under a state of great excitement, and was in my immediate charge. I was confident, however, that he would be subdued before the President finished his inaugural. To the surprise of everybody however, except, perhaps, the Cabinet, Mr. Lincoln did not consume five minutes in repeating it. As soon as the people outside saw that he was done, loud cries were raised for Johnson, upon which we hastily retreated to the Senate chamber, and closed the unhappy and inauspicious day.”3 The President later said: “I have known Andy for many years…he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared. Andy ain’t a drunkard.”4 Forney quoted the President as observing: “It has been a severe lesson for Andy, but I do not think he will do it again.”5 Forney was well versed on the situation since, according to Johnson biographer Hans Trefousee, “…on the night before the inauguration, he celebrated with his friend Forney, with whom he shared many glasses of whiskey.”7 Trefousse noted that Johnson had had at least three glasses of whiskey before he went to the Senate, going back to Hamlin’s Senate office to drink the third. Although Johnson was occasionally a heavy drinker, Trefousse determined that there was no evidence that Johnson was an alcoholic—unlike his two oldest sons, both of whom were alcoholics.

Frederick Douglass later contended that Johnson revealed another aspect of his character that day: “On this inauguration day, while waiting for the opening of the ceremonies, I made a discovery in regard to the vice president—Andrew Johnson. There are moments in the lives of most men, when the doors of their souls are open, and unconsciously to themselves, their true characters may be read by the observant eye. It was at such an instant I caught a glimpse of the real nature of this man, which all subsequent developments proved true. I was standing in the crowd by the side of Mrs. Thomas J. Dorsey, when Mr. Lincoln touched Mr. Johnson, and pointed me out to him. The first expression which came to his face, and which I think was the true index of his heart, was one of bitter contempt and aversion. Seeing that I observed him, he tried to assume a more friendly appearance; but it was too late; it was useless to close the door when al within had been seen. His first glance was the frown of the man, the second was the bland and sickly smile of the demagogue. I turned to Mrs. Dorsey and said, ‘Whatever Andrew Johnson may be, he certainly is no friend of our race.’7

Johnson became President on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, with whom he had served in Congress in the late 1840s and whom he visited on the afternoon of Mr. Lincoln’s assassination. Johnson himself lost one son and one son-in-law in the war. He had been a strong proponent of slavery before the War and a strong supporter of the Union once the war began. Johnson was unique among Southerner senators at the outbreak of the war in retaining his seat rather than supporting the Confederacy. He supported emancipation, but opposed the application of the Emancipation Proclamation to Tennessee and opposed the extension of rights and assistance to blacks after the war.

Obstinate and opinionated, insecure and class-conscious, well-dressed but frequently ill-tempered, Johnson as President quarreled with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and with Congress over Reconstruction and the Tenure of Office Act. He was impeached on February 24, 1868. Conviction failed by one vote—in part because of the weakness of the case and in part because of opposition to Senator Benjamin Wade succeeding Johnson as President. He sought vindication of his record and was reelected to Senate in 1875 shortly before his death—after losing elections for Senate in 1870 and Congress in 1872.

President Johnson was unable to move into the White House directly after President Lincoln’s assassination because Mrs. Lincoln was in no condition to move out. Robert Lincoln reported to the new President: “My mother and myself are aware of the great inconvenience to which you are subjected by the transaction of business in your present quarters but my mother is so prostrated that I must beg your indulgence. Mother tells me that she cannot possibly be ready to leave here for 2 1/2 weeks.”7 Although Johnson waited patiently to occupy the presidential quarters, his failure to pay the customary acts of condolence infuriated Mrs. Lincoln, who was sensitive to any slight of her husband or herself . She later wrote that “My own intense misery, has been augmented by the same thought—that, that miserable inebriate Johnson, had cognizance of my husband’s death…”9

Footnotes

- Samuel C. Williams, The Lincolns and Tennessee, p. 28.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Walter B. Stevens, A Reporter’s Lincoln, p. 156.

- John W. Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, pp. 39-40.

- H. Draper Hunt, Hannibal Hamlin: Lincoln’s First Vice President, pp. 197-198.

- John Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, p. 177.

- Hans Trefousse, Andrew Johnson, p. 188.

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p. 355.

- Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln, p. 249.

- William Hanchett, The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies, p. 83.

Visit

The Capitol

Hannibal Hamlin

Benjamin F. Wade

John W. Forney

Edwin M. Stanton

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Abraham Lincoln and Tennessee

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination