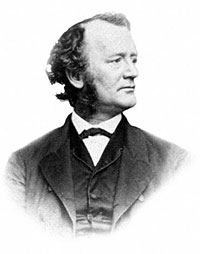

John W. Forney was the Editor of the Philadelphia Press (started in 1857) and the Washington Chronicle (started in 1861). Originally a War Democrat, Forney was appointed as Secretary of the Senate in 1861 with the support of President Lincoln. Forney was a political chameleon and rumor-monger who liked liquor too much for his own good.

As a Democrat, he had been an early promoter and ally of President James Buchanan in Pennsylvania, but Buchanan’s failure to deliver on expected patronage and newspaper appointments led Forney to become a Douglas Democrat. This, in turn, led to his appointment as Clerk of the House in 1858 in a deal between Douglas Democrats and Republicans. (It was Forney’s second stint in that office; he had served from 1851-1856.) Forney, according to historian James G. Randall, “took pleasure after the [1860] election in claiming that by supporting Douglas instead of going along with fusion he had done much to assist Lincoln’s victory.” Randall maintained Forney’s claims lacked validity because of the strength of both Mr. Lincoln and the tariff issue in Pennsylvania.1

As Secretary of the Senate, he frequently visited the President: “He delighted in parables and stories. His treasures of memory were inexhaustible. He never failed for an illustration. He liked the short farce better than the five-act tragedy. He would shout with laughter over a French, German, or negro anecdote, and he was always ready to match the best with a better. More than once, when I bore a message to him from the Senate, he detained me with some amusing sketch of Western life. He seemed to have read the character, and to know the peculiarities of every leading man in Congress and the country, and would play off many an innocent joke upon them.”2 But, noted Forney, Mr. Lincoln’s interests were not confined to humor: “He was, withal, a man of sentiment, reading Shakespeare like a philosopher, and remembering the best passages. A little poem written by Francis De Haes Janvier, of Philadelphia, called ‘The Sleeping Sentinel,’ was an especial favorite; and ‘The Patriot’s Oath’ and ‘Sheridan’s Ride,’ by Thomas Buchanan Read, were always recited at his request by Mr. Murdoch, whenever that loyal actor visited the metropolis.”3 In a speech after the Civil War, Forney told of an 1863 incident that recalled Mr. Lincoln’s ability to put people at ease:

Some two years ago, a deputation of colored people came from Louisiana, for the purpose of laying before the President a petition asking certain rights, not including the right of universal suffrage. The interview took place in the presence of a number of distinguished gentlemen. After reading their memorial, he turned to them and said: ‘I regret, gentlemen, that you are not able to secure all your rights, and that circumstances will not permit the government to confer them upon you. I wish you would amend your petition, so as to include several suggestions which I think will give more effect to your prayer, and after having done so please hand it to me.’ The leading colored man said: ‘If you will permit me, I will do so here.’ ‘Are you, then, the author of this eloquent production?’ asked Mr. Lincoln. ‘Whether eloquent or not,’ was the reply, ‘it is my work;’ and the Louisiana negro sat down at the President’s side and rapidly and intelligently carried out the suggestions that had been made to him. The Southern gentlemen who were present at this scene did not hesitate to admit that their prejudices had just received another shock.4

Civil War writer Ernest B. Furgurson wrote: “To evenings at his apartment on Capitol Hill, he invited great men not only of politics, but of the arts and sciences. The photographer Mathew Brady, the actors Joe Jefferson and Edwin Forrest and the portraitist Charles Loring Elliott were among the eminences who drank deep and talked long.”5

Forney starred in another capitol production: Andrew Johnson’s drunken inauguration as Vice President in March 1865. On March 3, Johnson attended a party at Forney’s home. Sick and perhaps hung-over the next morning, Johnson was given some liquor to fortify himself. It was the responsibility of Secretary of the Senate Forney to escort the inebriated Johnson into the Senate chamber, where the new Vice President delivered a speech that embarrassed Mr. Lincoln and other on-lookers.

Forney had supported Douglas in 1860, he said, in order to help Lincoln carry Pennsylvania. He helped arrange publication of some Lincoln speeches and helped printing contracts for Lincoln Administration. Forney was a political weathervane. He remained as Secretary of the Senate until 1868, first supporting President Andrew Johnson and then vociferously opposing him. He moved back to Philadelphia in 1868 and subsequently returned to the Democratic Party. Forney sought Senate seat from Pennsylvania (1866), opposed the policies of the Johnson Administration, and pushed for the presidential election of Ulysses S Grant in 1868. Throughout this period, he kept a hand in Pennsylvania politics—unsuccessfully opposing the election to the Senate in 1857 and 1867 of Simon Cameron, with whom he periodically fought and then was reconciled. Eventually, after serving as a Ulysses Grant appointee as Collector of the Port of Philadelphia, Forney returned to the Democratic Party.

Footnotes

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 198.

- John Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, p. 38-39.

- Forney, Anecdotes of Public Men, p. 167.

- Francis Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, pp. 267-268.

- Ernest B. Furgurson, Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War, p. 269.

Visit

Simon Cameron

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania

Stephen A. Douglas

Abraham Lincoln and Journalists

John W. Forney (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

The Journalists (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

President Lincoln at Gettysburg