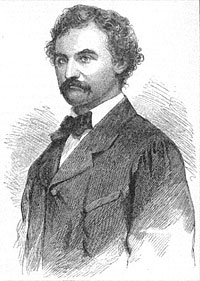

An attorney and Congressman from Maryland (Know-Nothing, Republican, 1854-61, 63-64), Henry Winter Davis was considered for Lincoln’s first cabinet and had heavy support from New England, his cousin David Davis, Thurlow Weed and William Seward, but lost out to his enemy, Montgomery Blair, who had more favorably impressed Lincoln. Indeed, he had not publicly supported Mr. Lincoln during the 1860 election and was not even a Republican at the time.

“Naturally, the congressman’s initial enthusiasm for Lincoln was damaged [as a result of his failed cabinet bid], but there is no indication from the available evidence that he was tremendously hostile toward him as a result of the episode. In fact, much of the bitterness Davis felt over his failure to obtain a cabinet portfolio was directed toward Montgomery Blair,” wrote Davis biographer Gerald S. Henig.1 Critics within the party also deprived him of an opportunity to move to the Senate a year later in March 1862.

Davis’ political philosophy was largely based on opposition to the Democrats; he was a fervent Whig and Know-Nothing before he finally became a Republican. A combative, volatile and brash chameleon who changed religion with the philosophical winds and parties with the political seasons, Davis became a thorn in President Lincoln’s side and a continual antagonist to the Blair family. He began the war as a critic of the Lincoln Administration’s abuse of civil liberties of suspected traitors and became an advocate for such policies. Although he had always been anti-slavery, the war also converted him into a fervent radical on slavery questions and advocate of immediate emancipation. He objected to the Emancipation Proclamation because he believed emancipation was a congressional prerogatives and because it failed to guarantee the rights of freedmen. As a border state Congressman, however, his pro-Republican votes and anti-Administration politics cost him his seat for two years. He was reelected in 1863 and sided with Radical Republicans. Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “To placate Henry Winter Davis, Lincoln gave him control of the Maryland patronage.”2

Congressman Davis and President Lincoln came into conflict over the appointment of a replacement for General Robert Schenck as commander of the Middle Department headquartered in Baltimore. According to historian Gerard S. Henig, “”Davis was unwilling to back down. Deeply fearful that Lockwood would side with the Blair faction, the congressman went to see Lincoln in late January [1864] to renew his request that Piatt, or at least Brigadier William Birney, the son of the famous abolitionist James G. Birney, be assigned the command. Lincoln refused ‘with more than usual bluntness.’ He said that he regarded Maryland affairs as ‘a personal quarrel & would do nothing to aid one set to vent their spite on another.’ Davis ‘instantly took his hat and left the room. ‘Of course,’ he later told Du Pont, ‘no retort was proper. The President’s remarks was of such a nature as to prevent further conversation.’ Moreover, Davis angrily noted, it was now apparent that Lincoln had become ‘thoroughly Blairized.'”3

Historian John Niven wrote that House Speaker Schuyler “Colfax had more than compensated for keeping Davis off the Committee on Naval Affairs by making him chairman of the foreign affairs committee. The Speaker was persuaded also to appoint Davis chairman of a select committee which would consider and report on reconstruction.”4 Davis was appointed chairman of the Select Committee on Rebellious States. Historian Herman Belz wrote: “In a speech at Philadelphia in September 1863 in which he considered the grounds on which Congress could legislate concerning the rebel states, [Congressman Henry Winter] Davis chose a middle position based on the clause of the Constitution guaranteeing to each state in the Union a republican form of government – the same position taken by Senator Harris in his reconstruction bill of February 1863.””5

Herman Belz wrote: “The measure which Henry Winter Davis reported in February 1864 from the Select Committee on the Rebellious States proposed to create provisional civil governments in the seceded states until new state governments could be organized….Besides proscribing former rebels and repudiating the Confederate debt, the most important provisions of the Davis bill sought to secure the Emancipation Proclamation and guarantee freedmen’s liberty and rights.”6

In 1864, Davis co-sponsored the Wade-Davis bill on reconstruction that was much tougher on allowing individuals and states to be reunited with the Union than President Lincoln desired. After Mr. Lincoln pocket vetoed the bill, Davis was enraged. He authored Wade-Davis Manifesto against lenient reconstruction policy and searched for an alternative candidate to Lincoln in 1864. The manifesto accused Mr. Lincoln of a “studied outrage on the legislative authority of the people” and “a rash and fatal act…a blow at the friends of his administration, at the rights of humanity, and at the principles of republican government.”7 The manifesto boomeranged—reinforcing support for the President and creating opposition in Maryland to Davis.

Davis’s propensity for vindictiveness did not serve him well. When Republicans planned a Union convention for Baltimore in June, noted historian Charles Bracelen Flood, Congressman Davis, in “a singularly spiteful act” had rented a more spacious hall for the convention “so it stood empty and unused.”8

Davis was defeated for reelection in 1864. “I’ve been told that insanity is hereditary in his family, and I think we will admit the plea in his case,” President Lincoln once said of him.9 When Mr. Lincoln was told Gustavus Fox on election night that Davis had been defeated, Fox added, “It served him right.” The President’s response was much more temperate: “You have more of that feeling of personal resentment than I. Perhaps I have too little of it; but I never thought it paid. A man has no time to spend half his life in quarrels. If any man ceases to attack me, I never remember the past against him.”10 Davis himself was much less magnanimous, writing a friend about Mr. Lincoln’s reelection, “We must for four years more rely on the forcing process of Congress to wring from that old fool what can be gotten for the nation.”11

Defeat did not demoralize Davis, who continued to press his own views of reconstruction in opposition to the President’s plans on Louisiana. But Davis’s opposition was tinged with reality. Davis responded to subsequent congressional criticism of his reconstruction bill by saying “That these discoveries have been made since the vote of last session is quite as remarkable as that they should have been overlooked before that vote. But they were neither overlooked before nor discovered sine…..It is the will of the President which as been discovered since.”12

Footnotes

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis, p. 153.

- Henig, Henry Winter Davis, pp. 196-197.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 55.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 475.

- Herman Belz, Reconstructing the Union: Theory and Policy During the Civil War, p. 134.

- Herman Belz, A New Birth of Freedom, p. 59.

- Henig, Henry Winter Davis, p. 216.

- Charles Bracelen Flood, 1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History, p. 131.

- Noah Brooks, Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, p. 208.

- John Nicolay and John Hay, Lincoln, Volume X, p. 377.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher, Lincoln in Text and Context, p. 201.

- Michael Les Benedict, A Compromise of Principle: Congressional Republicans and Reconstruction 1863-1869, p. 85.

Visit

Montgomery Blair

Frank P. Blair

David Davis

Benjamin Wade

Gustavus Fox

Biography (Link 2)

Abraham Lincoln and Maryland

Wade-Davis Bill (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)