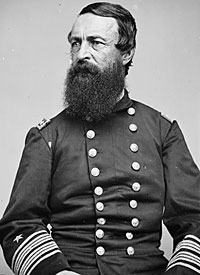

David Dixon Porter was a Union Navy admiral and son of War of 1812 naval hero David Porter. At the beginning of the war, Porter’s loyalty was questioned, given his close association with southerners like Jefferson Davis. Porter himself said he was headed to California to captain a mail boat and wait out the war. Instead, he commanded federal warship Powhatan that was sent by President Lincoln to relieve Fort Sumter in April 1861, but he was diverted to Fort Pickens in Florida by a mix-up in orders caused by Secretary of State William H. Seward and abetted by Porter. Porter was in the thick of the diversion, working closely with Army Captain Montgomery Meigs to devise the operation in conjunction with Secretary Seward, Porter continued the diversion even after Seward had reversed his position.

Porter’s determination to take the Powhatan to Fort Pickens led him to overcome all obstacles—including a last-minute message from Secretary Seward recalling him. He was especially persuasive in having Commander Andrew Foote desist from wiring Navy Secretary Gideon Welles for further orders. Porter himself quoted another naval commander on Porter’s devious conduct: “You ought to have been tried and shot; no one but yourself would ever have been so impudent.”1

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary: “Although Lieutenant Porter had gone with the Powhatan to Pensacola, there was no order or record in the Navy Department. He was absent without leave; the last sailing orders to the Powhatan were to Mercer. The whole proceeding was irregular anc could admit of no justification without impeaching the integrity or ability of the Secretaries of War and the Navy.”2 Welles wrote: “Porter had some of the qualities of Barron with more dash and energy, was less plausible, more audacious and careless in his statements, but like him was given to intrigues.”3

Historian Craig L. Symonds wrote: “Porter was something of a free spirit in the navy, a confident, even brash individual who was not averse to self-promotion. Lincoln’s secretary John Hay described him as ‘a ready offhand talker [with] a slight dash of the rowdy.’ For his part, Welles acknowledged that Porter had ‘dash and energy,’ but he was concerned that…he was ‘given to intrigues.’”4 Symonds wrote that “Porter was talented and energetic but he was also self-promoting, boastful, casual with the truth, and lacking in what Welles called ‘high moral qualities.’”5

On one of his frequent visits to the White House later in 1862, Porter recorded the aftermath of the Fort Sumter episode and how he came to be appointed to head a Mississippi River squadron:

I thought I would call, before leaving Washington, and pay my respects to the President. I found him in company with Mr. Seward, and both gentlemen seemed glad to see me.

‘What can I do for you, Captain,’ said the president.

‘Sir,’ I said, ‘I think of resigning from the navy and getting the merchants of New York to give me a suitable steamer, so that I may show the Navy Department how to catch the Alabama. That would suit my disposition better than superintending ironclads at St. Louis under Commodore Hull. I should fret my heart out there in a week suffering such an indignity; yet that’s what the Navy Department proposes doing with me.’

‘They shall not do it,’ said Mr. Seward, jumping up. ‘I have not forgotten how you helped me to save Fort Pickens to the Union.’

‘Yes,’ said the President, ‘and got me into hot water with Mr. Welles, for which I think he has never forgiven me. I believe he would forget it, but, Seward, you won’t let him. You are always flaunting your claimed success in his face, and deprecating the Fort Sumter expedition; it’s like shaking a red rag at a bull. If it hadn’t been for Seward, Captain, Mr. Welles would have tried you by court-martial for disobeying Seward’s telegram, although you were simply carrying out my written orders—a fact which none of us remembered until you were beyond our reach.’

‘You were right,’ said Mr. Seward, ‘in disobeying my orders,’ as it saved us Fort Pickens.’

‘Well,’ said Mr. Lincoln, ‘if the navy hasn’t broken the back-bone of the Rebellion I think it has come pretty near doing it, though, after all, Vicksburg slipped through our fingers, which was a great disappointment to me, realizing as I do, its great importance as a depot of supplies to the Confederates; however, if I live, you shall be at the take of the place.’

The President then made me describe the battle at the passage of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, making his usual shrewd comments on the matter.

‘I read all about it,’ he said; how the ships went up in line, firing their broadsides; how the mortars pitched into the forts; how the forts pitched into the ships, and the ships into the rams, and the rams into the gun-boat, and the gun-boats into the fire-rafts, and the fire-rafts into the ships. Of course I couldn’t understand it all, but enough to know that it was a great victory. I reminds me,’ continued the President, ‘of a fight in a bar-room at Natchez, but I won’t tell that now.

‘It struck me,’ continued the President, ‘that the fight at the forts was something like the Natchez scrimmage, only a little more so,’

‘Mr. President,’ I said, ‘that achievement of Farragut’s is the most important event of the war, and all that he has received for it is a vote of thanks of Congress. The British Government would have loaded him with honors and emoluments.’

‘How is that, Seward?’ said the President.

‘I don’t know anything about it,’ said the Secretary of State. ‘I am not the head of the Navy Department.’

‘No,’ replied the President, ‘but you don’t mind running off with a navy-ship when it suits your purposes.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Mr. Seward, ‘when I know it is the only way to save the honor of the nation; but Farragut will not be forgotten.’

The President then summoned a messenger and said, ‘Go tell the Assistant Secretary of the Navy that I wish to see him at once.’

I took my leave on the plea that I had to catch the train for Newport.

‘Good-by,’ said the President; ‘you sha’n’t go to St. Louis, you sha’n’t resign, and you shall be at Vicksburg when it falls.’6

Under Flag Officer David Farragut, Porter helped return New Orleans to Union control in April 1862. Smart and loyal but brash and impulsive, he was often at odds with superiors in the Navy, especially Secretary Gideon Welles and all Union generals like Benjamin Butler and Nathaniel Banks. However, working with Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, he had a key role in recapture of Union control of Mississippi River. The three military officials held a strategy conference with President Lincoln in Virginia in March 1865, shortly before the end of the war.

Porter later recalled that he “knew the President as an honest, faithful worker in his country’s cause, who did the best he could to bring the war to a speedy close, while at the same time he showed a determined spirit to yield nothing that would militate against the Republic of which he was the head. Although painted by his enemies in the blackest colors, President Lincoln had a heart capable of the greatest sympathy and the keenest emotions for the carnage and destruction he saw going on in every direction, and if necessary he would have sacrificed his life to avert these horrors. If Mr. Lincoln had never done more than the one act of abolishing slavery and wiping out that blot on our civilization, it would have been enough to immortalize him but if his biography is publicly written when prejudices are laid aside, so that the man can be seen in his greatness and integrity, no nobler character will adorn the pages of American history. The last days of President Lincoln’s life, except the two final ones, were passed in my company and mostly on board my flag-ship, and I take great satisfaction in the knowledge that he considered them the happiest days of his administration. He came to City Point, unaccompanied by any of his Cabinet, to witness what he knew was about to take place in the downfall of the Confederate stronghold. He was anxious for peace and was willing to extend the most liberal terms to those who had made war upon us. I kept from the President all those who would have annoyed him or disturbed the tranquillity he enjoyed on ship-board, and I think he was grateful for- my consideration.”7

After the war, Porter served as superintendent of the Naval Academy (1865-1868).

Footnotes

- David Dixon Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War, p. 22.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 25.

- Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 19.

- Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p. 19.

- Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals, p. 188.

- Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War, pp. 221-222.

- Osborn H. Oldroyd, editor, The Lincoln Memorial: Album-immortelles, pp. 399-400.

Visit

William H. Seward

Gustavus V. Fox

Montgomery Meigs

Benjamin Butler

Nathaniel Banks

William T. Sherman

Biography

The Officers (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)