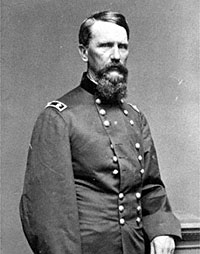

Francis P. Blair, Jr. was a Union general who served in Missouri and West. A Republican congressman from Missouri (1857-58, 1861, 1864) at the outset of the war, he organized pro-Union military units among German-Americans which were instrumental in keeping Missouri in Union. An early political backer of Edward Bates in 1860 and a military backer of John C. Frémont in 1861, he turned against Frémont’s military leadership in Missouri later in the year and was jailed. He was active in several campaigns in the West—including the battle of Chickasaw Bluffs and Sherman’s March to the Sea. In his memoirs, Ulysses S. Grant wrote of Frank Blair in July 1861: “There was no man braver than he, nor was there any who obeyed all orders of his superior in rank with more unquestioning alacrity.”1 One of the most irascible members of an irascible family, Frank was a leader of a moderate faction of the Missouri Republican Party called the “Claybanks,” who feuded with another radical group called the “Charcoals,” much to President Lincoln’s consternation.

When Congress convened in July 1961, Blair was defeated for the House speakership. He trailed Pennsylvania’Galusha Grow 71-40 on the first ballot and asked supporters to back Grow on the second ballot. In return Grow offered Blair the chairmanship of Ways and Means. Blair preferred to assume the chairmanship of the Military Affairs Committee. He took an active role in the special session that summer and declared on the House force that “the President [must] retain the confidence of the people of this country – all of who are in favor of preserving the Union.”2

“In early April [1862], Congress, with Frank’s support, voted for compensated emancipation for the District of Columbia. In the midst of this debate, Frank rose to make a spirited defense of the president on April 11,” wrote Blair biographer William E. Parrish. “To those who said that Lincoln had not policy, Frank argued that the president’s main concern lay in preserving the Union. Refusing to believe that the South had seceded strictly over the issue of slavery, Frank recalled those Southern leaders who had tried to pursue moderation, and then made it clear that he considered the real cause of the war to be the ‘negro question and not the slavery question.’” Blair argued against emancipation: “No wise man desires to increase the number of enemies to the State within the hostile regions, or divide its friend outside. Mr. Lincoln knew that a decree of emancipation simply would have this effect. Such an act he knew was calculated to make rebels of the whole of the non slaveholders of the South, and at the same time to weaken the sympathy of a large number of working men of the North, who are not ready to see their brethern in the South put on equality with manumitted negroes.”3

President Lincoln’s Secretary John Hay recalled that one night in early December 1863, he, John Nicolay, and Secretary of the Interior John Usher were in the president’s office discussing the Blairs when Mr. Lincoln came and observed: “The Blairs have to an unusual degree the spirit of clan. Their family is a close corporation. Frank is their hope and pride. They have a way of going with a rush for anything they undertake, especially have Montgomery and the Old Gentleman.”4

Mr. Lincoln wrote Montgomery Blair some advice for his brother on November 2, 1863: “I understood you to say that your brother, Gen. Frank Blair, desires to be guided by my wishes as to whether he will occupy his seat in Congress or remain in the field. My wish then is compounded of what I believe will be best for the country, and it is, that he will come here, put his military commission in my hands, take his seat, go into caucus with our friends, abide the nominations, help elect the nominees, and thus aid to organize a House of Representatives, which will really support the government in the war. If the result shall be the election of himself as speaker, let him serve in that position. If not let him retake his commission and return to the army for the country.”

Mr. Lincoln went on to write: “It will be a mistake if he shall allow the provocations offered him by insincere time-servers to drive him from the house of his own building. He is young yet. He has abundant talents—quite enough to occupy all his time without devoting any to temper. He is rising in military skill and usefulness. His recent appointment to the command of a corps by one so competent to judge as General Sherman proves this. In that line he can serve both the country and himself more profitably than he could as a member of Congress upon the floor.”5

Ramrod straight in physique and politics, Frank Blair was courageous and aggressive on the battlefield and political field. Blair abandoned Army to briefly serve in Congress in 1864 and twice vigorously attacked Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase on the House floor. One attack created a small crisis for Mr. Lincoln when the President—without knowing about the attack—immediately reappointed Blair to his old army rank without required Senate approval. In his diary entry of April 28, 1864, Gideon Welles described the aggressive way that the Blairs engaged in politics and war:

General Frank Blair has resigned his seat to the House, and the President has revoked the acceptance of his military resignation. This is a stretch of power and construction that I do not like. Much censure will fall on the President for this act, and it will have additional edge from the violent and injudicious speech of General Blair denouncing in unmeasured terms Mr. Chase. He also assails the appointees of Chase, and his general policy touching agent’s permits in the valley of the Mississippi as vicious and corrupt. I have an unfavorable opinion of the Treasury management there and on the coast, and there are some things in the conduct of Chase himself that I disapprove.

The Blairs are pugnacious, but their general views, especially those of Montgomery Blair, have seemed to me sound and judicious in the main. A forged requisition of General Blair has been much used against him. A committee of Congress has pronounced the document a forgery, having been altered so as to cover instead of $150 worth of stores some $8000 or $10,000. He charges the wrong the Treasury agents, and Chase’s friends, who certainly have actively used it. Whether Chase has given encouragement to the scandal is much to be doubted. I do not believe he would be implicated in it, though he has probably not discouraged, or discountenanced it. Chase is deficient in magnanimity and generosity. The Blairs have both, but they have strong resentments. Warfare with them is open, bold and unsparing. With Chase it is silent, persistent, but regulated with discretion. Blairs make no false professions. Chase avows no enmities.6

The Blairs, whose family owned slaves, represented the conservative wing of the Republican Party on emancipation. Frank Blair was the party’s “chief theoretician” for colonization of former slaves, according to historian Richard Sewell7 and the “best, most passionate, and most industrious proponent of a plan of gradual emancipation,” according to historian Allan Nevins.8 In Missouri, Blair had to battle the party’s more radical wing on slavery issues.

Before the war, he and brother Montgomery were law partners in St. Louis and he served as Attorney General for the New Mexico Territory. He ran unsuccessfully for Vice President on the Democratic ticket with Horatio Seymour in 1868 and served briefly in the Senate from Missouri in 1871. His strongly anti-Reconstruction views made him politically controversial in Missouri and across the country and doomed the family’s long-held dream to elect him President.

Footnotes

- William E. Parrish, Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative, p. 174.

- Parrish, Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative, p. 115.

- Parrish, Frank Blair: Lincoln’s Conservative, p. 138.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editors, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 123 (Diary entry of December 9, 1863).

- Roy M. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 555.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 20.

- Richard H. Sewell, Ballots for Freedom, p. 326.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln, Volume II, p. 163.

Visit

Montgomery Blair

Salmon P. Chase

Gideon Welles

Francis P. Blair, Sr.

Abraham Lincoln and Missouri

John A. McClernand (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Colonization (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)