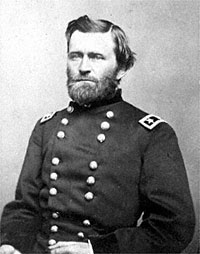

“Unconditional Surrender.” Union general who was a West Point graduate. He reentered the Army with difficulty in Civil War, but after capture of Fort Donelson, he swiftly rose to command Army of Mississippi, leading it to the capture of Vicksburg [in July 1863]. His occasional lapses into liquor were controlled by his wife and loyal lieutenants like John Rawlins and William T. Sherman. Loyal to his subordinates, straightforward and simple in his dealings with others, he was calm, stubborn and determined in battle.

Mr. Lincoln’s respect for Grant had grown during 1862 and 1863, On July 5, 1863 before he learned of the Union victory at Vicksburg, the President said of the western commander: “He doesn’t worry and bother me. He isn’t shrieking for reinforcements all the time….And if Grant only does thing down there—I don’t care much how, so long as he does it right—why, Grant is my man and I am his the rest of the war!”1 Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher “heard Mr. Lincoln say, on one occasion: ‘General Grant is the most extraordinary man in command that I know of. I heard nothing direct from him and wrote to him to know why, and whether I could do anything to promote this success, and Grant replied that he had tried to do the best he could with what he had: that he believed if he had more men and arms he could use them to good advantage and do more than he had done, but he supposed I had done and was doing all I could; that if I could do more he felt that I would do it.’ Lincoln said that Grant’s conduct was so different from other generals in command that he could scarcely comprehend it.'”2 The President’s attitude toward Grant was summed up in a letter he sent the Union commander on April 30, 1864:

“Not expecting to see you again before the Spring campaign opens, I wish to express, in this way, my entire satisfaction with what you have done up to this time, so far as I understand it. The particulars of your plans I neither know, or seek to know. You are vigilant and self-reliant; and, pleased with this, I wish not to obtrude any constraints or restraints upon you. While I am very anxious that any great disaster, or the capture of our men in great numbers, shall be avoided. I know that these points are less likely to escape your attention than they would be mine. If there is anything wanting which is within my power to give, do not fail to let me know it.

And now with a brave Army, and a just cause, may God sustain you.3

Against his wishes, Grant came to Washington and was named General-in-Chief of the Army in March 1864, in which capacity he served until 1869. “Word of his arrival having spread, he found on his return to Parlor 6 [of Willard’s Hotel] a special invitation to come by the White House, presumably for a conference with the Commander in Chief, whom he had never met although they both were from Illinois and were by now the two most famous men in the country,” wrote historian Shelby Foote. “If he had known that the President’s weekly receptions were held on Tuesday evenings he would perhaps have postponed his call, but by the time he completed the short walk up the avenue to the gates of the executive mansion it was too late. He found himself being ushered up the steps, through the foyer, down a corridor, and finally into the brightly lighted East Room, where the reception was in full swing. The crowd, enlarged beyond the norm tonight by the news that he would be there, fell silent as he entered, then parted before him to disclose at the far end of the room the tall form of Abraham Lincoln, who watched him approach, then put out a long arm for a handshake. ‘I’m glad to see you, General, he said.4

General Grant briefly visited the Army of the Potomac and then returned to the White House, where President Lincoln attempted to convince him to stay for dinner. When Grant asked to be excused, Mr. Lincoln responded: “But we can’t excuse you. Mrs. Lincoln’s dinner without you, would be Hamlet with Hamlet left out.” Responded Grant: “I appreciate the honor Mrs. Lincoln would do me, but time is very important now—and really—Mr. Lincoln, I have had enough of this show business.”5

Grant left town as soon as possible, returned to Nashville, and then came back to Washington to visit President Lincoln. At the White House again, he met privately with President Lincoln. Henry Halleck had told Grant not to brief Mr. Lincoln on his plans — and President Lincoln gave Grant a similar warning. Unlike previous generals, Grant had the President’s confidence—and Grant showed his confidence in the President by sharing his plans. Grant himself said later that Mr. Lincoln claimed “all he wanted or ever had wanted was someone who would take the responsibility and act, and call on him for all the assistance needed, pledging himself to use all the power of the government in rendering such assistance.”6

Grant moved his headquarters from the West to the East, where he and President Lincoln were in frequent contact. Calm and thoughtful, simple and direct, Grant collaborated with the nominal head of the Army of the Potomac, George Meade. Meade was as irritable as Grant was phlegmatic. Nevertheless, the two generals were a good team. Although Lincoln had confidence in Grant, he worried in 1864 that the general might harbor presidential ambitions and sent several emissaries to check on his political intentions.

Even before Grant was elevated to lieutenant general, President Lincoln attempted to gauge his political ambitions. He asked Congressman Elihu Washburne, who in turn referred him to Grant friend J. Russell Jones. Jones hurried to Washington with a letter he had received from Grant that stated: “Nothing could induce me to think of being a presidential candidate, particularly so long as there is a possibility of having Mr. Lincoln re-elected.” After reading the letter, Mr. Lincoln told Jones: “My son, you will never know how gratifying that is to me. No man knows, when that Presidential grub gets to gnawing at him, just how deep it will get until he has tried it; and I didn’t know but what there was one gnawing at Grant.”7

The President continued to test Grant’s presidential ambitions during 1864 through a variety of emissaries and informants, but he found that Grant lacked conflicting aspirations. When General Frank Blair, a Lincoln ally, wrote Grant about the election, Grant replied: “Everyone who knows me knows I have no political aspirations either now or for the future.” Grant instructed Blair to “Show this letter to no one unless it be the president himself.”8 According to historian David E. Long, “Certainly Grant had a preference in this election. The war and Lincoln had raised him from an insignificant officer to the highest rank and the most successful battlefield leader in U.S. history. He wrote Congressman Elihu B. Washburne on September 21, “I have no objection to the President using any thing I have ever written to him as he sees fit—I think however for him to attempt to answer all the charges the opposition will bring against him will be like setting a maiden to work to prove her chastity.'”9

Pennsylvania politician Alexander McClure found conflicting attitudes towards Grant when he visited the White House. Although the President worried about Grant’s political ambitions, President Lincoln also valued Grant’s fighting instincts: After the Battle of Shiloh, which Grant nearly lost on the first day, McClure visited the White House. Not always the most reliable witness, McClure later wrote:

So much was I impressed with the importance of prompt action on the part of the President after spending a day and evening in Washington that I called on Lincoln at eleven o’clock at night and sat with him alone until after one o’clock in the morning. He was, as usual, worn out with the day’s exacting duties, but he did not permit me to depart until the Grant matter had been gone over and many other things relating to the war that he wished to discuss. I pressed upon him with all the earnestness I could command the immediate removal of Grant as an imperious necessity to sustain himself. As was his custom, he said but little, only enough to make me continue the discussion until it was exhausted. He sat before the open fire in the old Cabinet room, most of the time with his feet up on the high marble mantel, and exhibited unusual distress at the complicated condition of military affairs. Nearly every day brought some new and perplexing military complication. He had gone through a long winter of terrible strain with McClellan and the Army of the Potomac; and from the day that Grant started on his Southern expedition until the battle of Shiloh he had had little else than jarring and confusion among his generals in the West. He knew that I had no ends to serve in urging Grant’s removal, beyond the single desire to make him be just to himself, and he listened patiently.

“I appealed to Lincoln for his own sake to remove Grant at once, and, in giving my reasons for it, I simply voiced the admittedly overwhelming protest from the loyal people of the land against Grant’s continuance in command. I could form no judgment during the conversation as to what effect my arguments had upon him beyond the fact that he was greatly distressed at this new complication. When I had said everything that could be said from my standpoint, we lapsed into silence. Lincoln remained silent for what seemed a very long time. He then gathered himself up in his chair and said in a tone of earnestness that I shall never forget: ‘I can’t spare this man; he fights.'”10

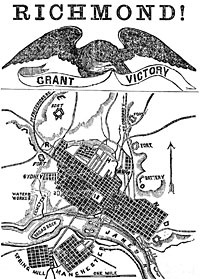

President Lincoln also had to worry about Grant’s military judgment on the way to Richmond in the spring of 1864 and the subsequent deadlock around Petersburg and Richmond. In the fall of 1864, President Lincoln summoned General Grenville Dodge to the White House and interrogated him over lunch. Mr. Lincoln “finally led up to the placed where he asked me the question of what I thought about Grant, and what I thought about his next campaign. Just as he asked the question, we got up from the table. I answered, ‘Mr. President, you know we western men have the greatest confidence in General Grant; I have no doubt, whatever, that in this next campaign he will defeat Lee—how, or when is to do it, I cannot tell, but I am sure of it.’ He took my hand in both of his and very solemnly said, ‘You don’t know how glad I am to hear you say that.'”11

Grant seldom visited the White House between the time he was appointed to head the Union armies in 1864 and the day President Lincoln was assassinated. One Sunday afternoon, a month after President Lincoln had named him a lieutenant general, William O. Stoddard came to the President’s office and asked Mr. Lincoln, who was resting on the sofa, what kind of man Grant was: “Well…I hardly know what to think of him, altogether. He’s the quietest little fellow you ever saw,” said the President. “Why, he makes the least fuss of any man you ever knew. I believe two or three times he has been in this room a minute or so before I knew he was here. It’s about so all around. The only evidence you have that he’s in any place in that he makes things git! Where he is, things move!” Unlike other generals, the President told Stoddard, Grant did not look for excuses to avoid an advance. “When Grant took hold I was waiting to see what his pet impossibility would be, and I reckoned it would be cavalry as a matter of course, for we hadn’t horses enough to mount even what men we had. There were fifteen thousand or thereabouts up near Harper’s Ferry, and no horses to put them on. Well, the other day, just as I expected, Grant sent to me about those very men; but what he wanted to know was whether he should disband them or turn ’em into infantry.”12

After the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5-6, President Lincoln awaited news from General Grant. A New York Tribune reporter brought a report and a personal message from General Grant: “He told me I was to tell you, Mr. President, that there would be no turning back.” President Lincoln was so frustrated by Union generals who had turned back that he kissed the Tribune reporter.13

Grant aide Horace Porter wrote ‘that the president did not pretend to thrust military advice upon his commander, but only modestly suggested his views.”14 Grant biographer Jean Edward Smith wrote: “Lincoln and Grant deserve the nation’s credit for saving the United States, eradicating slavery, and striving to provide equality for the freedman. One could not have succeeded without the other. And while Lincoln set the course, it was Grant who sailed the ship.”15

Grant had served in Mexican-American War and resigned from army in 1854 to try a series of farming and business ventures, all of which were failures. He was working as a clerk for his brother in Galena, Illinois at the outbreak of the Civil War.

Grant was subsequently elected to two corruption-plagued terms as President (1869-1877) before embarking again on a series of disastrous business ventures. He never did have any luck in business. He was a far better general and writer than he was a politician, president, or public speaker.

Footnotes

- Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865, p. 215.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 393.

- Roy M. Basler, editor, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 324.

- Shelby Foote, Civil War, Volume III, p. 6.

- Isaac Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 371.

- Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command, p. 143.

- Harry J. Maihafer, The General and the Journalists: Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley, and Charles A. Dana, p. 184.

- Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865, p. 257.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, pp. 227-228.

- Alexander McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 193-194.

- Grenville M. Dodge, Personal Recollections of President Abraham Lincoln, General Ulysses S. Grant and General William T. Sherman, p. 20.

- William O. Stoddard, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, pp. 197-199.

- Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865, p. 301.

- Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant, pp. 302-303.

- John Y. Simon, Harold Holzer, and Dawn Vogel, editors, Lincoln Revisited, p. 180 (Jean Edward Smith, “Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant”).

Visit

John A. McClernand

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

East Room

Alexander McClure

Charles A. Dana

Edwin M. Stanton

George Meade

The War Department

Willard’s Hotel

William O. Stoddard

Elihu Washburne

William T. Sherman

David Dixon Porter

Benjamin Butler

Biography

Biography (Link 2)

Appomattox Courthouse National Historic Park

National Historic Site

Battle of Shiloh

Abraham Lincoln and Cotton

Ulysses S. Grant (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief