The Lincoln’s White House entertainments were largely free of either real entertainment or extensive refreshments. Some small dinner parties were held mid-week in the State Dining Room. It may have been in the State Dining room where the Lincoln family and their guests sat down to their first meal on March 4, 1861. It had been thoughtfully planned by the niece of outgoing President James Buchanan, who had acted as her uncle’s official hostess. According to Elizabeth Grimsley, it was “most thoroughly appreciated.”1

The first formal use of the State Dining Room came on March 28, 1861 when the President hosted a dinner honoring his new Cabinet — an occasion marked by both political and social tension. “Every detail was formal, the men in black, the ladies in ball gowns, with jewelry and flowers in their hair. At seven the party gathered in the Blue Room; they were joined by the President and Mrs. Lincoln. [John Nicolay] made the necessary introductions,” wrote White House historian William Seale. “The Marine Band played as they marched to the State Dining Room, where they took their prescribed places, according to Nicolay’s seating chart, composed very carefully in conference with Secretary of State [William Seward.] Flowers and ferns were massed on the great gilded plateau. Gas and candle light illuminated the textures of mirrors, gilt, silver, and crimson and white damask.”2

“Lincoln’s seating charts survive, showing about forty at a long, rectangular table, with the president and Mrs. Lincoln facing each other halfway down the table and the president’s secretaries at each end. The president was always served first. No one was to rise from the table before the president, and guests were not free to depart from the house before the president retired,” Seale wrote in The White House: The History of an American Idea.3 Nicolay himself detested this part of his job, according to his daughter Helen, because of the difficulty of anticipating personal and political animosities: “Worst of all, some last-minute illness or caprice might cause an expected guest to send a ‘regret,’ which of course upset the whole apple cart, and the work had to be done over again. This was a hard assignment for a young man who had come to America in an emigrant ship and had grown up in the woods and in a country printing office. How painstakingly he solved such problems is shown by his neat diagrams of the banquet table, the ladies’ names in decorative red ink, the gentleman’s in black…”4

At that first state dinner after post-prandial cigars in the Red Room President Lincoln explained to the Cabinet about General Scott’s startling recommendation that Forts Sumner and Pickens should be evacuated. The dinner party ended even more somberly than it had begun. But William Howard Russell noted that the President tried to break the pre-dinner conversation:

“In the conversation which occurred before dinner, I was amused to observe the manner in which Mr. Lincoln used the anecdotes for which he is famous. Where men bred in courts, accustomed to the world, or versed in diplomacy, would use some subterfuge, or would make a polite speech, or give a shrug of the shoulders as the means of getting out of an embarrassing position, Mr. Lincoln raises a laugh by some bold west-country anecdote, and moves off in the cloud of merriment produced by his joke. Thus, when Mr. Bates was remonstrating apparently against the appointment of some indifferent lawyer to a place of judicial importance, the President interposed with, ‘Come, now Bates, he’s not half as bad as you think. Besides that, I must tell you, he did me a good turn long ago. When I took to the law, I was going to court one morning, with some ten or twelve miles of bad road before me, and I had no horse. The judge overtook me in his wagon. ‘Hollo, Lincoln! Are you not going to the courthouse? Come in and I’ll give you a seat.’ Well, I got in, and the judge went on reading his papers. Presently the wagon struck a stump on one side of the road; then it hopped off to the other. I looked out, and I saw the driver was jerking from side to side in his seat; so says I, ‘Judge, I think your coachman has been taking a little drop too much this morning.’ ‘Well I declare, Lincoln,’ said he, ‘I should not much wonder if you are right, for he has nearly upset me half-a-dozen times since starting.’ So, putting his head out of the window, he shouted, ‘Why, you infernal scoundrel, you are drunk!’ Upon which, pulling up his horses, and turning round with great gravity, the coachman said, ‘By gorra! That’s the first rightful decision you have given for the last twelve-month.” Whilst the company were laughing, the President beat a quiet retreat from the neighborhood of the Attorney-General.

It was at last announced that General Scott was unable to be present, and that, although actually in the house, he had been compelled to retire from indisposition, and we moved in to the banqueting-hall. The first ‘state dinner,’ as it is called, of the President was not remarkable for ostentation. No liveried servants, no Persic splendour of ancient plate, or chefs d’oeuvre of art glittered round the board. Vases of flowers decorated the table, combined with dishes in what may be called the ‘Gallo-American’ style, with wines which owed their parentage to France, and their rearing and education to the United States, which abound in cunning nurses for such productions. The conversation was suited to the state dinner of a cabinet at which women and strangers were present. I was seated next Mr. Bates and the very agreeable and lively Secretary of the President, Mr. Hay, and except when there was an attentive silence caused by one of the President’s stories, there was a Babel of small talk round the table, in which I was surprised to find a diversity of accent almost as great as if a number of foreigners had been speaking English.

After dinner the ladies and gentlemen retired to the drawing room, and the circle was increased by the addition of several politicians.

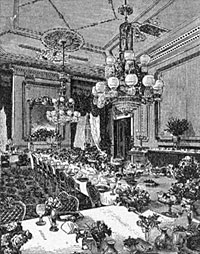

A dinner for 34 members of the diplomatic corps was held on June 4, 1861. The Washington Star described it “in many respects, the most brilliant affair of the sort that has ever taken place in the Executive Mansion. Through the good taste of Mrs. Lincoln, the stiff, artificial flowers heretofore ornamenting the Presidential tables were wholy discarded and their places delightfully supplied by fragrant, natural flower. The blue room was decorated with cut flowers; and the chandeliers gracefully festooned with wreaths and flowers, indeed the senses of sight and smell were delighted at every turn by beautiful and fragrant pyramids and wreaths from the floral riches of the White House conservatories and grounds. The dinner was served in a style to indicate that Mrs. Lincoln’s good taste and good judgment had exercised supervision in this department.”5

On August 3, 1861, a special reception was held in honor of France’s Prince Napoleon. “Today, Mary has a large dinner-party for the Prince Napoleon and suite. There will be no ladies except Mary and myself. I wish it was over,” White House guest Elizabeth Grimsley wrote her family. “Tell Cousin Mary she could scarcely realize there was to be a dinner-company of 30 in the house today. What a comfort to be able to entertain and feel no care over it.” 6 The visiting Frenchmen were clearly more impressed with General Winfield Scott and General George B. McClellan than with the President. Lieutenant-Colonel Camille Ferri Pisani, one of Napoleon’s aides, described an unimpressive meeting between Mr. Lincoln and the French party earlier in the afternoon. He wrote:

“That same evening the Prince dined with the President. We met, gathered in the White House, with the ministers and the leading members of Congress. But, for us at least, the main attraction of our presidential dinner was the presence of a new element, contrasting in all respects with the governmental element, and overshadowing it today in importance – I mean the military. This group was represented by General Scott and General McClellan.

“General Scott is a man of huge stature. Seventy-five years old, he is afflicted with gout and walks painfully, so he entered the room leaning on the arm of the young General on whose shoulders rest the hopes of the Union, General McClellan. Furthermore, it is easy to realize that General Scott belongs to another generation, as much as by his manners as by his age. He is a real gentleman, a type of old British general, well educated and well bred, and perfectly acquainted with the military history of Europe – that of First Empire principally, in which he has too often the weakness of looking for points of comparison with his own career.7

There were more intimate evenings as well. On Christmas evening, 1861, the Lincolns hosted a group of friends and Administration officials for dinner – including eight members of the extended Blair family — Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and his wife, Blair’s wife Francis P. Blair and sister Elizabeth Lee, his brother General Frank Blair and his wife, Assistant Secretary of the Nav Gustavus Fox. Other guests that night were Illinois Secretary of State Jesse Dubois, Illinois Senator Orville H. Browning, Kentucky Congressman Charles A. Wickliffe and his wife, as well as the pastor of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, Dr. Phineas Gurley, and his wife. Earlier in the day, the President had met with his Cabinet and decided to relinquish two Confederate officials held in a Boston jail in order to end a diplomatic crisis with England.

On at least one occasion in 1861, Willie and Tad Lincoln were permitted to attend a state dinner along with their playmates, Holly and Bud Taft, sitting near the foot of the dining table. “I tell you those ‘bassadors were all tied up with gold cords; they glittered grand,” Tad later told Julia Taft. “Pa looked pretty plain with his black suit, but Ma was dressed up, you bet,” added Willie.8

The height of 1862 social season was to be a massive party on February 5 to show off the redecoration of the White House which Mrs. Lincoln had supervised. Dinner got off to a late start at 11 P.M., but when the guests were ready to enter, the key to the door to the dining room could not be found. When the guests finally entered, according to historian Margaret Leech : “Costly wines and liquors flowed freely, and the immense Japanese punch bowl was filled with ten gallons of champagne punch. There was nearly a ton of turkeys, ducks, venison, pheasants, partridges and hams, and the tables were loaded with the confectionery inspirations of Maillard. A fountain was held aloft by nougat water nymphs. Hives, swarming with lifelike bees, were filled with charlotte russe. War was gently hinted by a helmet, with waving plumes of spun sugar. The good American frigate, ‘Union,’ with forty guns and all sails set, was supported by cherubs draped in the Stars and Stripes. Fort Pickens sat in sugar on a side table, surmounted by deliciously prepared birds. At two o’clock the party was still going on, and Mrs. Lincoln’s triumph had only one flaw. Her two little boys had taken cold, and Willie had a worrisome fever. Several times during the evening, both the mother and father went upstairs to bend over his bed, where Mrs. Keckley was in attendance. Lincoln’s face was grieved and anxious, and in greeting General Frémont he spoke of Willie’s illness.”9 By 3 a.m., virtually all of the 1000 guests had left and the Lincolns were left to their private trials.

Willie’s death combined with etiquette of war to limit such events. Representatives of 11 seceded states would have been missing. Representatives of some European states which hoped for Confederate success were not much more welcome. There were plenty of generals in the Washington neighborhood available for social occasions but regulations barred them from Washington without special permission. As a result, Mrs. Lincoln’s purchase of a set of formal Haviland china for the State Dining Room got little formal use. But at the end of the President’s first term, a “cabinet dinner had been planned, and Nicolay, who addressed the invitations, discovered that Mrs. Lincoln had omitted the names of [Salmon Chase] and his son-in-law and daughter, Governor and Mrs. William Sprague,” wrote historian Benjamin P. Thomas. “Foreseeing the social crisis that was certain to result, Nicolay took up the matter with Lincoln, who declared that Chase and the Spragues must be invited. ‘Whereat,’ wrote Nicolay, ‘there rose such a rampage as the House hasn’t seen in a year,’ Young [William Stoddard] ‘fairly cowered at the volume of the storm, and I think for the first time begins to appreciate the awful sublimities of nature.'”10

For state dinners the regular staff was entirely inadequate; a French caterer was called in, who furnished everything, including waiters,” wrote Guard William Crook. ” It fell to Mrs. Lincoln to choose the set of china which the White House needed at this stage. It was, in my opinion, the handsomest that has ever been used there. In the centre was an eagle surrounded by clouds; the rim was a solid band of maroon. The coloring was soft and pretty, and the design patriotic.”11

The State Dining Room was also used as a classroom for Willie, Tad, Bud and Holly Taft in late 1861 before Willie’s death broke up the quartet of play and school mates. Julia Taft recalled: “In the fall of 1861, Mrs. Lincoln had a desk and blackboard put into the end of the state dining room and secured a tutor for the boys. She asked my brothers to share his instruction as there were no schools open in Washington at this time. My father insisted on paying half the tutor’s salary but Mrs. Lincoln said she had secured a placed for him in one of the departments and he would spend his mornings there and teach the boys in the afternoon. The boys were doing well, thought the younger pair were a little unruly….”12 Later, Alexander Williamson tutored Tad here alone.

Painter Francis Carpenter finished and displayed his painting of the Emancipation Proclamation here in 1864 before its presentation in the East Room: “At the end of six months’ incessant labor, my task at the White House drew near completion,” recalled Carpenter. On the 22nd of July, the President and Cabinet, at the close of the regular session, adjourned in a body to the State Dining-room, to view the work at last in a condition to receive criticism. Sitting in the midst of the group, the President expressed his ‘unschooled’ opinion, as he called it, of the result, in terms which could not but have afford the deepest gratification to any artist.”13

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, “Six Months in the White House,,Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society19 (Oct.-Jan., 1926-27) p. 46.

- William Seale,History of the White House, p. 367.

- Seale,The White House: The History of an American Idea, p. 108.

- Helen Nicolay,Lincoln’s Secretary, p. 79.

- Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, “Six Months in the White House,,Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society19 (Oct.-Jan., 1926-27) p. 57.

- Harry E. Pratt, editor,Concerning Mr. Lincoln, p. 87.

- Camille Ferri Pisani,Prince Napoleon in America, 1861, p. 103.

- Julia Taft Bayne,Tad Lincoln’s Father, pp. 168-169.

- Margaret Leech,Reveille in Washington, p. 297.

- David Herbert Donald,We Are All Lincoln Men, p. 196.

- Margarita Spalding Gerry, editor,Through Five Administrations: Reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook, pp. 17-18.

- Julia Taft Bayne,Tad Lincoln’s Father, p. 153.

- Francis Carpenter,Six Months at the White House, p. 350.

Visit

Thomas Lincoln

William Wallace Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln

John G. Nicolay

Francis Carpenter

Winfield Scott

William O. Stoddard

Julia Taft

Red Room