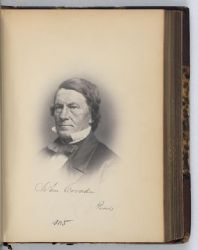

“Honest John” Covode was a Congressman from Pennsylvania (Republican, 1855-1871) who served on the Committee on the Conduct of the War. He was a radical on the topics of race and the war.

Covode was aggressive in personal relations and in his defense of the Union. He visited President-elect Lincoln in Springfield and urged that Simon Cameron not be appointed to the Cabinet – even signing a petition to that effect. He also pushed his own list of patronage appointments for Philadelphia on the President in April 1861. But after the fall of Fort Sumter in 1861. Covode’s focus shifted. “Pennsylvania is on the war-path,” wrote Lincoln aide John Hay. “John Covode offers to take $50,000…to arm the militia.”1

Covode was also aggressive in investigating government abuse. According to historian Bruce Tap, “Covode was already experienced in congressional investigations. As a member of the 36th Congress, he chaired a committee charged with investigating the alleged frauds in the James Buchanan administration.”2 The 1860 report of his Committee of Public Expenditures was a great embarrassment to Buchanan. Hay wrote of Covode’s inquiries as the days “when you could not beat an official thicket without scaring up a lively covey of frauds and thefts, and when patriots in the minority might cry aloud and spare not against the minions of a pampered despotism, and put the galleries to sleep, while rousing the hoarse murmurs of the rural districts.”3

Covode’s inquiries extended into the Lincoln administration. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote in early 1863: “On my way to Cabinet-meeting this A.M. met [John] Covode and Judge Lewis of Pennsylvania. The two had just left the President and presented me with a card from him to the effect that Covode had investigated the case of Chambers, Navy Agent at Philadelphia, and that if I saw no objection he should be removed. Told them I was going to the President and the subject should have attention. When I mentioned the subject, the President wished me to look into the case and see that all was right. He had not, he said, examined it, but passed it over to me, who he knew would.”4

Covode ran for the GOP nomination for governor of Pennsylvania in 1863. He lost and was replaced on the committee by Benjamin F. Loan of Missouri. John Hay wrote in his diary in October 1863: “Dining in company with [Assistant Attorney General] T. J. Coffey today he says Covode is still in a bewildered sate trying to understand why he was beaten for the nomination for Governor & why Bill Mann did not make a better use of the $1000 dollars [sic] he gave him to buy delegates. Coffey claims a sort of proprietorship in Covode as he sent him to Congress first.”5

About this time, Congressman Covode told Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase that he “thought Gov. Curtin and his friends designed that he should be brought forward as a candidate for the Presidency, and that, if elected Governor he would shape matters in Pennsylvania so as to secure its delegates in the Convention, while a majority of the loyal men of Pennsylvania preferred me, and that the vote of the State controlled by Curtin would not be given to me unless under some arrangement which would pledge to Gov. Curtin and his friends the patronage in Pennsylvania.” Writing in his diary, Chase continued: “To this I replied that no speculations as to Gov. Curtin’s future course could excuse the loyal men from supporting him now; that the future must take care of itself; that I was not anxious for the Presidency; that there was but one position in the Government which I really we’d like to have, if it were possible to have it without any sacrifice of principle or public interest, and that was the Chief Justiceship, and that should the wishes of our political friends incline to me as a nominee for the Presidency, those wishes be entirely of a public nature, for I certainly would never consent under any circumstances to make pledges as to appointments to office, but would insist upon being left entirely free to avail myself of the services of the best men in the country.”6

“Covode was not a man who paid any attention to the rules of etiquette,” recalled General Herman Haupt, the railroad engineer who was introduced to the President by Covode. “He took me to the White House, and without sending a card, walked up stairs, then along the hall to a room, opened the door without knocking, and ushered me into the August presence of Abraham Lincoln. The President was alone, seated in a chair, tilted back, with his heels upon the sill of an open window, clad in a linen duster, for the weather was warm.

Covode was greeted very cordially, and then I was introduced with some rather extravagant words of commendation, when Covode remarked: ‘Mr. President, I always thought it strange that the first time we met we seemed to know each other, and I think I have discovered the reason. You are called ‘Honest Abe’ and I ‘Honest John,’ and honest men are so might scarce in Washington that, of course, we knew each other at sight.7

The President laughed, but his response to Covode was not always so agreeable. He probably chafed under Covode’s alleged demands in late1863 that he dismiss Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and Attorney General Edward Bates. As a leader of the National Union League Committee, Covode’s opinions carried additional weight. Earlier, Covode had been frequently critical of General George B. McClellan. According to Haupt, Covode said: “McClellan has been raised to so high a pinnacle that he is afraid to move in any direction for fear that he will fall and break his neck.”8 After the Battle of Fredericksburg, Haupt reported on the situation to Covode, who took him to the White House. President Lincoln in turn took the Congressman and the General to see General Henry W. Halleck.

Covode often complained to President and one day his criticism caused Mr. Lincoln to snap. Haupt had once again accompanied Covode to the White House: “It was a period of gloom. We found the President much depressed. Covode reported the dissatisfaction in the army and the criticisms on his policy, and had proceeded for some time, when the President suddenly turned, placed his hand upon his knee and said: ”Covode, stop! Stop right there! Not another word! I am full, brim full up to here.”9 The President concluded by pulling his hand in front of his throat.

Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg reported that Covode visited the White House a few days later “to find the President in his office walking back and forth with a troubled face. As to whether he would issue the [Emancipation] Proclamation, said the President: ‘I have studied that matter well; my mind is made up….It must be done. I am driven to it. There is no other way out of our troubles. But although my duty is plain, it is in some respects painful, and I trust the people will understand that I act not in anger but in expectation of a greater good.”10

Covode’s own expectations were wide-ranging. After General Hiram G. Battle was killed at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Covode wired the President: “The death of Genl Berry makes room for Genl [David B.] Birney’s promotion. I do hope it will be made.”11 The same day, he joined a Kansas Senator and Representative to urge the retention of a general who had fallen afoul of the state’s governor.

Covode was businessman whose wealth was largely based on coal, wool and railroads. After an absence of two terms, Covode rejoined Congress in 1867 and served until his death.

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, p. 57 (April 16, 1861).

- Bruce Tap, “Amateurs at War: Abraham Lincoln and the Committee on the Conduct of the War,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Volume 23, Number 2, Summer 2002, p. 3.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864, p. 184 (December 28, 1861).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 218 (January 8, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 95 (October 19, 1863).

- David H. Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet, p. 180 (August 30, 1863).

- Herman Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt, pp. 297-298.

- Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt, p. 306.

- Haupt, Reminiscences of General Herman Haupt, p. 298.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln, The War Years, Volume II, p. 14.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois (Letter from John Covode to Abraham Lincoln, May 12, 1863).

Visit

Herman Haupt

Salmon P. Chase

Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania