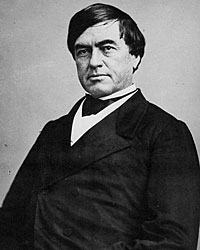

Nicknamed “Cash”, Cassius M. Clay was a Kentucky Republican leader and fervent abolitionist newspaper editor. He sought to maneuver the Republican presidential nomination for himself in 1860 and later a Cabinet post for himself in 1861. He lost Republican Vice Presidential nomination to Hannibal Hamlin in 1860 because as a former Whig he would not have balanced the ticket.

Historian William Ritchie wrote: ”After the election of Lincoln, Clay hoped that the portfolio of war was assured him. When strong opposition developed against him, Clay sought the assistance of other men of influence, such as Chase and Schurz. Clay failed to secure the appointment to the cabinet. He blamed William Seward, who said that Clay’s appointment to the cabinet would constitute a declaration of war on the South.”1 But there is little evidence that Clay was seriously considered for that post.

“My first interview with Mr. Lincoln was in company with some of his intimate personal friends, who called informally to pay their respects to him as the President of the United States. When the salutations and congratulations were being made to Mr. Lincoln, one of his secretaries placed some papers on his table for signature,” recalled Clay. “Mr. Lincoln excused himself for the moment by this remarks: ‘Just wait now until I sign some papers, that this government may go on.’”2

Pugnacious and pugilistic, sharp-tongued and sharp-penned, he organized the Strangers’ Guard in Washington at the beginning of the Civil War. It has special responsibility for guarding the White House, a residence that Clay had long desired to occupy on an elected basis. “As commander, Clay enlivened the atmosphere at his headquarters in Willard’s Hotel with his braggadocio. With three pistols strapped to his waist, and an elegant sword hanging at his side, he talked to anyone who would listen about his Mexican War exploits and his political battles,” wrote Clay biographer David L. Smiley. “John Hay, private secretary to President Lincoln, could hardly suppress his laughter at the droll picture Clay presented., Hay remarked that clay ran up and down the White House steps ‘like an admirable vignette to 25-cents worth of yellow-covered romance.’ At Willard’s, Hay declared, Clay spent his time talking and drinking coffee…”3

Biographer H. Edward Richardson wrote: “As commander of the Clay Battalion, Clay guarded the Navy Yard, cleared the city of masses of southern sympathizers, and protected the White House until the Federal regiments arrived on the scene.”4 Clay had offered his services to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. Cameron protested : “I don’t believe I ever heard of where a foreign minister volunteered in the ranks.” Clay replied: “Then let’s make history.”5

Clay was appointed Minister to Russia in April 1861 after he objected to appointment as Minister to Spain and was rejected for the positions he preferred in either England or France. He returned to America to accept a commission as a general. He resigned his army post in protest against failure to proclaim emancipation of slaves in the South. Despite his notable lack of common sense, humility or diplomatic skills, he sought reappointment Minister to Russia as Simon Cameron tired of the job. “Although you may not always represent my special views, you have always my confidence and support to carry out your own—for you are the Chief of the Nation—not I,” Clay told Mr. Lincoln.6 President Lincoln reappointed Clay despite Senate opposition. This time, Clay remained in Russia until 1869. Without slavery as an issue, Clay had no political agenda.

But first, Mr. Lincoln had to deal with Clay’s complaints and lectures. In August 1862, Clay had an interview with the President in which he pressed his claims to be secretary of war. Mr. Lincoln was quick to reject his claim: “Who ever heard of a reformer reaping the rewards of his work in his lifetime? I was advised that your appointment as secretary of war would have been considered a declaration of war upon the South. I have no objection to your return to St. Petersburg. I thought that you had desired to return home; at least, [Secretary of State William H. Seward] so stated to me.”7 Shortly before his reappointment, Senator Orville Browning spent an evening with Mr. Lincoln on December 12, 1862:

Went to the Presidents at 6 P.M. and had a talk with him. Among other things he said there was never an army in the world, so far as he could learn, of which so small a percentage could be got into battle as ours—That 80 pr cent was what was usual, but that we could never get to exceed 60. That when he visited the army after the battles of South Mountain and Antietam he made a count of the troops, and there were only 93,000 present when the muster rolls showed there should be 180,00. Whilst I was with him Cassius M. Clay & some other gentlemen sent in their cards. He was much annoyed—said to me he did not wish to see them, and finally told the servant to tell them he was engaged and could not see them to-night.

I asked him what he thought of Clay. He answered that he had a great deal of conceit and very little sense, and that he did not know what to do with him, for he could not give him a command—he was not fit for it.

He had asked to be permitted to come home from Russia to take part in the war. Since he wanted some place to put Cameron to get him out of the War Department he consented, and appointed Clay a Majr Genl hoping the war would be over before he got home. That when he came he was dissatisfied and wanted to go back, and was not willing to take a command unless he could control every thing—conduct the war on his own plan, and run the entire machine of Government—That could not be allowed, and he was now urging to be sent back to Russia. What embarrassed him was that he had given him his promise to send him back if Cameron resigned.8

Historian Michael Burlingame described Clay as “vain, melodramatic.” Burlingame wrote: “Lincoln came to regret offering a commission [in the army] to Clay. In December 1862, the ‘much annoyed’ president refused to see that general, saying Clay had ‘a great deal of conceit and very little sense and that he did not know what to do with him, for he could not give him a command – he was not fit for it.”9

In 1854 during the campaign against the Kansas-Nebraska, Clay visited Springfield and spoke there. Lincoln scholar Daniel Mark Epstein wrote: “On July 8, the Lincolns read in the paper that Mary’s childhood friend from Lexington, the forty-three-year-old abolitionist Cassius Clay, was coming to Springfield on Monday, July 10, to give a speech in the state house rotunda in the afternoon. She remembered him as a muscular, short-necked man with a handsome, large head and furious eyes.” Clay was denied use of the State Capitol so his meeting was held outdoors. Epstein wrote: “The day was clear and cool, as the temperature, which had been in the nineties, had dropped over the weekend into the low seventies. The crowd that gathered outside the statehouse to hear the charismatic orator at 1:30 was directed by the organizers – Lincoln’s friend Orville Browning and Judge Thomas Moffett – to reconvene in a grove five blocks away, southwest of the square.” Clay that “The Declaration of Independence asserted an immortal truth. It declared a political equality – equality as to personal, civil and religious rights.”10

Clay broke with Republicans in 1872 and was beset by mental illness before his death. Clay had been born to wealth, but squandered much of it on ill-advised business ventures, including proprietorship of the anti-slavery newspaper, The True American. He was an ardent emancipationist with fundamentally racist beliefs. Because of his political beliefs, he was subject to political and physical attacks—which he countered with his bowie knife expertise. In 1878, Clay divorced his wife of 45 years and briefly married a 15-year-old girl.

Footnotes

- William Ritchie, The Public Career of Cassius M. Clay, p. 9.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 316.

- David L. Smiley, Lion of White Hall: The Life of Cassius M. Clay, p. 176.

- H. Edward Richardson, Cassius Marcellus Clay: Firebrand of Freedom, p. 83.

- Robert Baughhman Carlée, The Last Gladiator, p. 133.

- Smiley, Lion of White Hall: The Life of Cassius M. Clay, p. 187.

- Don E. and Virginia Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 107.

- Theodore Pease, editor, Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Volume II, pp. 598-599.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, pp. 140, 290.

- Daniel Mark Epstein, The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage, p. 169.

Visit

David Hunter

James Lane

Simon Cameron

John Hay

East Room

Willard’s Hotel

Biography

Abraham Lincoln and Kentucky

White Hall (Clay home)