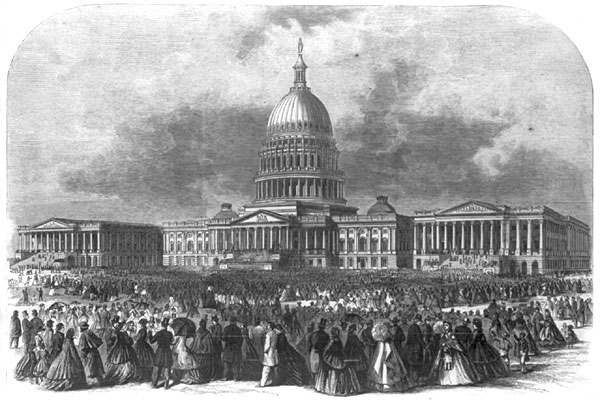

Mr. Lincoln’s Second Inauguration on March 4, 1865 was drizzling at first, but a burst of sun during his oath of office was interpreted by Mr. Lincoln as a good omen. Lincoln aide John Nicolay later wrote in a letter to his fiancée: “The ceremonies passed off yesterday in as pleasant a manner as was possible. The morning was dark and rainy, and the streets were very muddy; nevertheless large crowds were out in the procession and at the Capitol. I think there were at least twice as many at the [Capitol] as four years ago. Just at the time when the President appeared on the East Portico to be sworn in, the clouds disappeared and the sun shone out beautifully all the rest of the day.1

“There was a fall of rain with hail on the 4th of March, 1865, recalled journalist L.A. Gobright. An hour before noon, the inaugural procession left from the War Department for the Capitol without a key participant. According to Gobright, “Mr. Lincoln did not occupy the position assigned to him in the carriage, (Third in the procession,) as he had been at the Capitol during the entire morning, engaged in signing bills. Mrs. Lincoln, accompanied by Senators [James] Harlan and [Henry B.] Anthony, was driven to the head of the line, and preceded the procession to the Capitol. A platoon of marshals pioneered the carriage of Mrs. Lincoln, the escort being composed of the Union Light Guard. The crowd generally mistook the carriage of the President’s wife for that of the President, and under this delusion cheered it all along the route.” Gobright reported: “In the Senate chamber were members of Congress, Vice-Admiral Farragut, Major-Generals Banks and Hooker, the diplomatic corps, governors, and ex-governors of States and Territories, the mayors of Washington and Georgetown, Heads of Departments, officers who had received the thanks of Congress, Judges of the Supreme Court, and many others of prominence.”2

President Lincoln had arrived early in order to sign congressional legislation before the outdoors ceremony and the preceding indoors swearing of Vice President Andrew Johnson. Johnson, who had been sick with typhoid and usually did not drink, took liquor to fortify himself before delivering his inaugural speech. Clearly, he was drunk when he got up. “For twenty minutes did he run on about Tennessee, adjuring Senators to do their duty when she sent two Senators here, urging that she never was out of the Union, etc. In vain did [outgoing Vice President Hannibal] Hamlin nudge him from behind, audibly reminding him that the hour for the inauguration ceremony had passed; he kept on, though the President of the United States sat before him patiently waiting for his tirade to be over,” wrote Noah Brooks for the Sacramento Daily Union.3 One member of the Senate, Zachariah Chandler, wrote his wife: “The inauguration went off very well except that the Vice President Elect was too drunk to perform his duties and disgraced himself and the Senate by making a drunken foolish speech. I was never so mortified in my life, had I been able to find a hole I would have dropped through in out of sight.”4

In the inauguration audience was John Wilkes Booth, who later told a fellow actor: “What a splendid chance I had to kill the President on the 4th of March.”5 Brooks continued in his dispatch to California:

When the cortege of the President filed out upon the platform from the rotunda it was followed by a host of spectators from the Senate and passages. Instantly the bases of the columns, the statuary groups and every ‘coigne of vantage’ swarmed with people. The crush of crinolines was terrific, but vast crowds saw the sight to a good advantage from the great steps of the Capitol, which rose behind the platform and from the wings on either side. Before was a literal sea of heads, tossing and surging, as far as the eye could reach, among the budding foliage of the park opposite. Cheer upon cheer arose, bands b[e]lated upon the air and flags waved over all the scene. The Sergeant-at-Arms of the Senate, Brown by name, arose and bowed with his shiny black hat in dumb show before the crowd, where thereupon became still, and Abraham Lincoln, rising, tall and gaunt, over the crowd about him, stepped forward to read his Inaugural Address, printed in two broad columns upon a half-sheet of foolscap. As he rose, a great burst of applause shook the air, and died far away on the outer fringes of the crowd like a sweeping wave upon the shore. Just then the sun, which had been obscured all day, burst forth in its unclouded meridian splendor and flooded the spectacle with glory and light. Every heart beat quicker at the unexpected omen…

The inaugural…was well received and well pronounced, every word apparently being audible as the clear, light tones of the President rang out over that vast throng. There was applause at the words: ‘Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish;’ and the cheer was injected long enough to make a pause before he said, ‘And the war came.’ There was applause at other points, and a long burst when the crowd, with moist eyes, had listened to these words, which might be printed in letters of gold:

‘With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.’

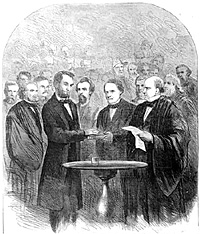

Silence restored, the President turned toward Chief Justice Chase, who held up his right hand, with his left upon the Book, held up by the Clerk of the Supreme Court, and administered the oath of office, the President laying his right hand upon the open page; then solemnly repeated ‘So help me God!’ he bent forward and reverently kissed the Book, and rose inaugurated President of the United States for four years from March 4, 1865. A salvo of artillery boomed upon the air, cheer upon cheer arose below, and, after bowing to the assembled host, the President retired within, resumed his carriage, and the procession escorted him back to the White House.6

Historian Phillip Shaw Paludan wrote: “In the greatest of his speeches, Lincoln never once mentioned the people, nor democracy, nor the triumph of a free people’s government over its enemies. What he did focus upon is a worldview, a frame of mind and heart that is probably fundamental to any democracy.”7

Poet Walt Whitman observed President Lincoln from a distance – never actually meeting Mr. Lincoln. Typically, he watched the President’s passage to and from his second inauguration:

The President very quietly rode down to the Capitol in his own carriage by himself, on a sharp trot, about noon, either because he wished to be on hand to sign bills, or to get rid of marching in line with the absurd procession – the muslin temple of liberty and pasteboard monitor.

I saw him on his return, at three o’clock, after the performance was over. He was in his plain two-horse barouche, and looked very much worn and tired; the lines, indeed, of vast responsibilities, intricate questions, and demands of life and death cut deeper than ever upon his dark brown face; yet all the old goodness, tenderness, sadness, and canny shrewdness underneath the furrows. (I never see that man without feeling that he is one to be become personally attached to for his combination of purest, heartiest tenderness, and native Western form of manliness.)

By his side sat his little boy of ten years. There were no soldiers, only a lot of civilians on horseback, with huge yellow scarves over their shoulders, riding around the carriage. (At the inauguration four years ago he rode down and back again surrounded by a dense mass of armed cavalrymen eight deep, with drawn sabres; and there were sharpshooters stationed at every corner on the route.)8

Sergeant Smith Stimmel was part of the President’s bodyguard that day. He later wrote: “Soon after the President concluded his address, he entered his carriage, and the procession started up Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, the escort from our Company following next to his carriage. Shortly after we turned onto Pennsylvania Avenue, west of the Capitol, I noticed the crowd along the street looking intently, and some were pointing to something in the heavens toward the south. I glanced up in that direction, and there in plain view, shining out in all her starlike beauty, was the planet Venus. It was a little after midday at the time I saw it, possibly near one o’clock; the sun seemed to be a little west of the median, the star a little east. It was a strange sight. I never saw a star at that time in the day before or since. The superstitious had had many strange notions about it, but of course it was simply owing to the peculiarly clear condition of the atmosphere and the favorable position of the planet at that time. The President and those who were with him in the carriage noticed the star at the same time.”9

Journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “There were many cheers and many tears as this noble address was concluded. Silence being restored, the President turned toward Chief Justice Chase, who, with his right hand uplifted, directed the Bible to be brought forward by the clerk of the Supreme Court,” wrote journalist Noah Brooks. “Then Lincoln, laying his right hand upon the open page, repeated the oath of office administered to him by the Chief Justice, after which, solemnly saying, ‘So help me God,’ he bent forward and reverently kissed the Book, then rose up inaugurated President of the United States for four years from March 4, 1865.” According to Gobright, “At the conclusion of the ceremonies, a salute was fire, the band struck up “Hail to the Chief,” and the thousands in attendance greeted the President with repeated huzzas.” Later, Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase gave the Bible to Mrs. Lincoln, marking the pages from Isaiah 5:27-28 which the President kissed:

None shall be weary nor stumble among them; none shall slumber nor sleep; neither shall the girdle of their loins be loosed, nor the latchet of their shoes be broken:

Whose arrows are sharp, and all their bows best, their horses’ hoofs shall be counted like flint, their wheels like a whirlwind.10

Historian Allan Nevins observed: “This Inauguration Day was vastly different from that of March 4, 1861, when people awaited the words of the newly elected President on the crisis momentarily descending on the nation. Now a tremendous shout, ‘prolonged and loud, arose from the surging sea of humanity’ that spread in waves from the specially built platform on the east front of the Capitol, out to the foliage of the Capitol grounds.”10 Historian Jay Winik wrote: “Lincoln was so exhausted after the inauguration ceremonies that he took to his bed for several days. By March 14, he would feel so ill that he would conduct a cabinet meeting in his bedroom.”12

On less ceremonial occasions, the President’s secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay were charged with carrying messages from President Lincoln to the Capitol. Nicolay and Hay rode in a two-horse carriage, noted their assistant, William Stoddard. But Stoddard was more likely to take a street car if he himself had message duty: “Up the steps to the eastern portico and into the building, not at all as a private individual, a citizen, but as something from the White House, reaching into this other side of the National Government. Both Houses must be visited, but both will receive you in the same manner. We will visit the House of Representatives after having looked in at the Senate. You are carrying something in the nature of a paper latch-key, and the door before you seems to open of itself, so prompt is the ready doorkeeper to recognize the presence of an errand from the Executive. He walks into the chamber of Representatives with you, just as an eloquent member is denouncing some feature of the misconduct of the war, and his eloquence is suddenly interrupted.”13

Footnotes

- Helen Nicolay, Lincoln’s Secretary, pp. 224-225.

- Lawrence A. Gobright, Recollection of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century, pp. 341-343.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 166.

- Http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAjohnsonA.htm.

- Thomas Reed Turner, Beware the People Weeping, p. 71.

- Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, pp. 167-169.

- Phillip S. Paludan, Lincoln’s Legacy: Ethics and Politics, p. 11.

- Walter Lowenfels, editor, Walt Whitman’s Civil War, edited by, pp. 258-259.

- Smith Stimmel, Personal Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, pp. 71-72.

- Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C. in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Nedwspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, p. 214.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, Volume IV, p. 27.

- Jay Winik, April 1865, p. 39.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 79.

Visit

Second Inaugural Address Text

Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Speech

John Hay

John G. Nicolay

Noah Brooks

Andrew Johnson

Lawrence A. Gobright

East Room: Second Inaugural Levee