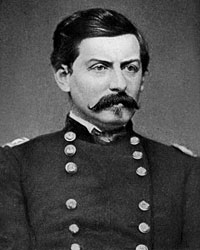

George B. McClellan, known as “Little Mac” and “Little Napoleon,” was the Union General who served as both Commander of the Army of the Potomac and General in Chief after the resignation of General Winfield Scott (whom McClellan circumvented) in November 1861. He maintained his headquarters in Washington during the winter of 1861-62 at the Southeast Corner of H Street and Madison Place, near the White House on Lafayette Square. It was owned by Navy Captain Charles Wilkes whose seizure of two confederate emissaries created the Trent affair in late 1861.

McClellan had resigned from the Army in 1857 and became general superintendent of Illinois Central Railroad and a supporter of Stephen Douglas in 1858 Senate race. Some early victories in West Virginia led to his appointment to head the Union Army of the Potomac on July 27, 1861. Historian William C. Davis wrote: “Immediately upon assuming command, McClellan began the work of rebuilding the army, both physically and spiritually. Under understood, as did Lincoln, the importance of being seen by the men, and soon scheduled as series of reviews and inspections, even while the work of drilling that Lincoln directed go under way.”1

McClellan almost immediately began a campaign to undermine and replace Winfield Scott, head of the Union armies. He had contempt for Scott and virtually all civilian authorities. On October 10, 1861, he wrote his wife: “When I returned yesterday after a long ride I was obliged to attend a meeting of the Cabinet at 8 pm. & was bored & annoyed. There are some of the greatest geese in the Cabinet I have ever seen—enough to tax the patience of Job… “2 A month later on November 17, he wrote his wife: “I went to the White House shortly after tea where I found ‘the original gorilla,’ about as intelligent as ever. What a specimen to be at the head of our affairs now!”3 He later recalled his early associations with Mr. Lincoln in a more favorable light: “My relations with Mr. Lincoln were generally very pleasant, and I seldom had trouble with him when we could meet face to face. I believe that he liked me personally, and certainly he was always much influenced by me when we were together. During the early part of my command in Washington he often consulted with me before taking important steps or appointing general officers.”4

McClellan got seriously ill in December 1861 and all plans for a Union offensive stalled while pressure for movement grew. On January 6, 1862, President Lincoln called a special cabinet meeting with several generals and the members of the Committee on the Conduct of the War. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, later an ardent critic of McClellan, defended him at this meeting: “I expressed my own views, saying that, in my judgment, Genl. McClellan was the best man for the place he held known to me— that, I believed, if his sickness had not prevented he would by this time, have satisfied everybody in the country of his efficiency and capacity —that I thought, however, that he tasked himself too severely—that no physical or mental vigor could sustain the strains he imposed on himself, often on the saddle nearly all day and transacting business at his rooms nearly all night that, in my judgment, he ought to confer freely with his ablest and most experienced Generals, deriving from them the benefits which their counsels, whether accepted or rejected, would certainly impart, and communicating to them full intelligence of his own plans of action, so that, in the event of sickness or accident to himself, the movements of the army need not necessarily be interrupted or delayed. I added that, in my opinion, no one person could discharge fitly the special duties of Commander of the Army of the Potomac, and the general duties of Commanding General of the Armies of the United States; and that Genl. McClellan, in undertaking to discharge both, had undertaken what he could not perform. Much else was said by various gentlemen, and the discussion was concluded by the announcement by the President that he would call on Genl. McClellan, and ascertain his views in respect to the division of the commands.”5 After several such planning sessions, McClellan feared that his authority was being usurped and arrived in person to reestablish his command.

Still, however, McClellan delayed an advance and chose a strategy with which the President disagreed but acquiesced. It wasn’t until March 1862 that McClellan finally put the Army of the Potomac in movement toward Richmond. The President’s frustration was reflected when he told the wife of an administration official: “Suppose a man whose profession it is to understand military matters is asked how long it will take him and what he requires to accomplish certain things, and when he has had all he asked and the time comes, he does nothing.”6 The Peninsula Campaign itself was slow; McClellan was defeated in the Seven Days’ Battles (June 25-July 1, 1862). Plagued by a “siege mentality” of warfare, he had a habit of overestimating the Confederate forces he faced and underestimating his ability to move expeditiously against them. He felt that Secretary of War Stanton and President Lincoln had deserted him. “Honest A has again fallen into the hands of my enemies & is no longer a cordial friend of mine!” he wrote his wife.7

McClellan’s difficulties in command were exacerbated by the fact the McClellan seldom went anywhere near actual fighting. He was a workaholic and superb organizer who had the unquestioned loyalty of his troops. Unfortunately, he understood how to generate loyalty only from those below his authority, not from those above himself. The result was friction between himself and the President, the Secretary of War and the congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War. The animosity of his key generals to General John Pope contributed to the second Union defeat at Bull Run on August 29-30, 1862.

McClellan was given command of the defenses of Washington on September 1, 1862 and then asked to “rectify the evil” of commanders who were not cooperating with General Pope in the retreat from Bull Run. McClellan was again given command of the Army of the Potomac before the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862—despite strong opposition to him within Congress and the cabinet. McClellan held off the Confederates because a Union soldier recovered General Robert E. Lee’s battle plans.

Historian Stephen R. Taaffe noted: “Lincoln visited the Army of the Potomac in early October, and although he pledged to protect McClellan from his domestic political enemies, there were plenty of signs in the following weeks that the president’s continued support depended upon McClellan’s aggressive prosecution of the war. A few days later, Lincoln peremptorily ordered the Army of the Potomac to advance, but McClellan responded with his usual litany of excuses. On 13 October, Lincoln admonished McClellan for his excessive timidity in a private letter designed to spur him on, but this tactic proved no more fruitful than his more direct approach the previous weeks. Instead, McClellan continued to demand more equipment, supplies, and men.”8

McClellan was relieved of command on November 5, 1862 for his failure to pursue Confederate Army. “For organizing an army, for preparing an army for the field, for fighting a defensive campaign, I will back General McClellan against any general of modern times. I don’t know but of ancient times, either. But I begin to believe that he will never get ready to go forward!’ the President told an aide shortly before he removed McClellan.9

McClellan’s “slows” generated a number of stories that Mr. Lincoln shared with visitors to his office: “McClellan’s tardiness reminds me of a man in Illinois whose attorney was not sufficiently aggressive. The client knew a few law phrases, and finally, after waiting until his patience was exhausted by the non-action of his counsel, he sprang to his feet and exclaimed: “Why don’t you go at his with a fi.fa., demurrer, a capias, a surrebutter, or a ne exeat, or something, and not stand there like a nudum pactum, or a non est.”10 On other occasion, the President told a visitor: “With all his failings as a soldier, McClellan is a pleasant and scholarly gentleman. He is an admirable engineer, but he seems to have a special talent for a stationary engine.”11 The President told assistant William O. Stoddard “Well, Stoddard, for organizing an army, for preparing an army for the field or for fighting a defensive campaign, I will back General McClellan against any general of modern times—I don’t know but of ancient times also. But I begin to feel as if he would never get ready to fight!'”12

McClellan opposed emancipation and his loyalty to the Union was questioned by members of the Joint Committee on Conduct of the War. He was the Democratic candidate for President in 1864 although he opposed the party’s anti-war platform. The split between pro-war and anti-war Democrats helped insure President Lincoln’s reelection. The day after the November 8, 1864 election, presidential aide Edward Duffield Neil entered Mr. Lincoln’s office: “Turning away from the papers which had been occupying his attention, he spoke kindly of his competitor, the calm, prudent general and grate organizer, whose remains this week have been placed in the cold grave. He told me that General Scott had recommended McClellan as an officer who had studied the science of war, and had been in the Crimea during the war against Russia, and that he told Scott that he knew nothing about the science of war, and it was very important to have just such a person to organize the raw recruits of the republic around Washington.”13 Shortly thereafter, McClellan resigned his army commission and departed for Europe.

After the war, McClellan earned a living as an engineering consultant before election as Governor of New Jersey (Democrat, 1878-1881).

Footnotes

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men.

- Letter to Mary Ellen McClellan, Stephen Sears, editor, Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan, p. 106.

- Letter to Mary Ellen McClellan, Sears, pp. 135-136.

- Colin R. Ballard, The Military Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 104.

- David Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase, pp. 57-58.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 163.

- Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond, p. 157.

- Stephen R. Taaffe, Commanding the Army of the Potomac, p. 53

- William O. Stoddard, Abraham Lincoln: The Man and the War President, p. 274.

- Isaac Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 297.

- Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 300.

- William O. Stoddard, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 160.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 602.

Visit

McClellan Headquarters

The War Department

The Winder Building Annex

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Henry W. Halleck

John Pope

Ambrose E. Burnside

Winfield Scott

Biography

Peninsula Campaign

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln and George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief