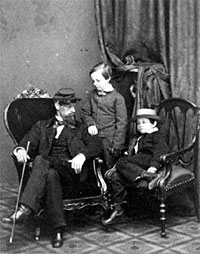

“Willie” was named after Mary Todd’s brother-in-law, Dr. William Wallace. He was a handsome, smart, serious and thoughtful child who was the favorite of Mary Todd Lincoln and her husband. Her cousin, Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, described Willie as a “noble, beautiful boy of nine years, of great mental activity, unusual intelligence, wonderful memory, methodical, frank and loving, a counterpart of his father, save that he was handsome.”1 Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote: “He was an avid reader, a budding writer, and generally sweet-tempered, all reminiscent of his father.”2 Julia Taft, who sometimes oversaw his play with her brothers, described Willie as “the most lovable boy I ever knew, bright, sensible, sweet-tempered and gentle-manner.” But Willie did not relish public attention, complaining: “I wish they wouldn’t stare at us so. Wasn’t there ever a President who had children?”3

Born in 1850, Willie died on February 20, 1862 of a typhoid-like disease. His death was traumatic for the entire family. Willie was studious, personable, intelligent and creative—the child who most closely reflected his father’s personality. His death was probably caused by the contaminated water that flowed through a nearby canal that provided water for the White House and a place for White House children to play. He was attended to by Dr. Robert K. Stone, the family physician. His parents were in nearly constant attendance during his illness as Willie literally wasted away and in constant grief after his death. Mrs. Lincoln “did all a mother ought or could during Willie’s sickness—she never left his side at all after he became dangerous, & almost wore herself out with watching, and she mourns as no one but a mother can at her son’s death,” reported Benjamin B. French.4 All the folk medicines in Washington—and many were given to Willie from Peruvian bark to beef tea—could not save him.

“It is hard, hard, hard to have him die!” said his father after Willie’s death. Illinois Senator Orville Browning assumed responsibility for the funeral and burial arrangements while his wife comforted Mary Todd Lincoln. Lincoln scholar Daniel Mark Epstein wrote: “Having made arrangements with the morticians Brown and Alexander, Browning dutifully attended the embalming on February 21, in the presence of the family doctors and Isaac Newton, Lincoln’s commissioner of agriculture. Frank T. Sands was the chief undertaker. Perhaps it was he who suggested the precaution of covering the breast of the corpse with the green and white blossoms of the mignonette (Reseda adorata), known for its overpoweringly sweet fragrance. Little Willie, pathetically wasted was dressed in one of his old brown suits, white socks, and low-cut shoes, like an ill-used marionette.”5

Historian Michael Burlingame wrote: “Between the time of Willie’s death and his funeral, an applicant for a postmastership barged into the White House clamoring to see the president. When Lincoln emerged from his office inquiring about the commotion, the importunate office seeker demanded an interview, which was granted. Upon learning what his caller wanted, he angrily asked: ‘When you came to the door here, didn’t you see the crepe on it? Didn’t you realize that mean somebody must be lying dead in this house?’”6

The funeral took place in the East Room while Willie’s body reposed in the Green Room. Rev. Dr. Phineas Gurley eulogized Willie: “His mind was active, inquisitive, and conscientious; his disposition was amiable and affectionate; his impulses were kind and generous; and his words and manners were gentle and attractive. It is easy to see how a child, thus endowed, would, in the course of eleven years, entwine himself round the hearts of those who knew him best; nor can we wonder that the grief of his affectionate mother today is like that of Rachel weeping for her children, and refusing to be comforted because they were not.”7 His funeral took place on a blustery day; the President was accompanied to the cemetery by Robert Lincoln, and Senators Lyman Trumbull and Orville Browning. “The funeral is a very solemn affair, but it cannot be permitted to interfere overmuch with work. The burden is increased rather than laid aside,” wrote presidential aide William Stoddard.8

Willie’s death after a two-week illness plunged his mother into inconsolable grief. She remained in formal mourning for a year and wrote of him: “I always found my hopes concentrating on so good a boy as he.” She donated her son’s savings to the Sunday School Mission Program at New York Avenue Presbyterian Church; his whole church school class had attended the funeral. The words poet Nathaniel Parker Willis wrote about Willie in Home Journal were of great comfort to his grieving mother.

This little fellow had his acquaintances among his father’s friends, and I chanced to be one of them. He never failed to seek me out in the crowd, shake hands, and make some pleasant remark; and this, in a boy of ten years of age, was, to say the least, endearing to a stranger. But he had more than mere affectionateness. His self-possession—aplomb, as the French call it— was extraordinary. I was one day passing the White House, when he was outside with a play-fellow on the side-walk. Mr. Seward drove in, with Prince Napoleon and two of his suite in the carriage; and, in a mock-heroic way—terms of intimacy evidently existing between the boy and the Secretary—the official gentleman took off his hat, and the Napoleon did the same, all making the young prince President a ceremonious salute. Not a bit staggered with the homage, Willie drew himself up to his full height, took off his little cap with graceful self-possession, and bowed down formally to the ground, like a little ambassador. They drove past, and he went on unconcernedly with his play: the impromptu readiness and good judgment being clearly a part of his nature. His genial and open expression of countenance was none the less ingenuous and fearless for a certain tincture of fun; and it was in this mingling of qualities that he so faithfully resembled his father.

With all the splendor that was around this little fellow in his new home he was so bravely and beautifully himself—and that only. A wild flower transplanted from the prairie to the hothouse, he retained his prairie habits, unalterably pure and simple, till he died. His leading trait seemed to be a fearless and kindly frankness, willing that everything should be as different as it pleased, but resting unmoved in his own conscious single-heartedness. I found I was studying him irresistibly, as one of the sweet problems of childhood that the world is blessed with in rare places; and the news of his death (I was absent from Washington, on a visit to my own children, at the time) came to me like a knell heard unexpectedly at a merry-making.

On the day of the funeral I went before the hour, to take a near farewell look at the dear boy; for they had embalmed him to send home to the West—to sleep under the sod of his own valley—and the coffin-lid was to be closed before the service. The family had just taken their leave of him, and the servants and nurses were seeing him for the last time— and with tears and sobs wholly unrestrained, for he was loved like an idol by every one of them. He lay with eyes closed— his brown hair parted as we had known it— pale in the slumber of death; but otherwise unchanged, for he was dressed as if for the evening, and held in one of his hands, crossed upon his breast, a bunch of exquisite flowers—a message coming from his mother, while we were looking upon him, that those flowers might be preserved for her. She was lying sick in her bed, worn out with grief and overwatching.

The funeral was very touching. Of the entertainments in the East Room the boy had been—for those who now assembled more especially—a most life-giving variation. With his bright face, and his apt greetings and replies, he was remembered in every part of that crimson-curtained hall, built only for pleasure—of all the crowds, each night, certainly the one least likely to be death’s first mark. He was his father’s favorite. They were intimates—often seen hand in hand. And there sat the man, with a burden on his brain at which the world marvels—bent now with the load at both heart and brain—staggering under a blow like the taking from him of his child! His men of power sat around him—McClellan, with a moist eye when he bowed to the prayer, as I could see from where I stood; and Chase and Seward, with their austere features at work; and senators, and ambassadors, and soldiers, all struggling with their tears—great hearts sorrowing with the President as a stricken man and a brother. That God may give him strength for all his burdens is, I am sure, at present the prayer of a nation.”9

Dr. Phineas Gurley wrote: “Willie’s death was a great blow to Mr. Lincoln, coming as it did in the midst of the war, when his burdens seemed already greater than he could bear. The little boy was always interested in the war and used to go down to the White House stables and read the battle news to the employees and talk over the outcome. These men all loved him and thought for one of his years, he was most unusual. When he was dying he said to me, ‘Doctor Gurley, I have six one dollar gold pieces in my bank over there on the mantel. Please send them to the missionaries for me.’ After his death those six one dollar pieces were shown to my Sunday School and the scholars were informed of Willie’s request.”8 At the funeral, Rev. Gurley said: “The beloved youth whose death we now and here lament was a child of bright intelligence and of peculiar promise. He possessed many excellent qualities of mind and heart which greatly endeared him not only to the family circle but to all his youthful acquaintances and friends. His mind was active, he was inquisitive and conscientious; his disposition was amiable and affectionate. Hi impulses kind and generous; his words and manners were gentle and attractive. It is easy to see how a child thus endowed could, in the course of eleven years entwine himself around the hearts of those who knew him best; nor can we wonder that the grief of affectionate mother today is like that of Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they were not.”11

General George McClellan wrote the President: “I have not felt authorized to intrude upon you personally in the midst of the deep distress I know you feel in the sad calamity that has befallen you and your family. Yet I cannot refrain from expressing to you the sincere and deep sympathy I feel for you. You have been a kind and true friend to me in the midst of the great cares and difficulties by which we have been surrounded during the past few months. Your confidence has upheld me when I should otherwise have felt weak. I wish now only to assure you and your family that I have felt the deepest sympathy in your affliction.”10 Both Lincolns struggled with their grief. Mary told her half-sister later that “if I had not felt the spur of necessity urging me to cheer Mr. Lincoln, whose grief was as great as my own, I could never have smiled again.”13

A more humble — and probably more appreciated — source of presidential comfort than General McClellan was William Florville, a black barber from Springfield: “I was surprised about the announcement of the death of your son Willie. I thought him a smart boy for his age, so considerate, so manly, his knowledge and good sense far exceeding most boys more advanced in years. Yet the time comes to all, all must die. Tell Taddy that his and Willie’s dog is alive and kicking, doing well. He stays mostly at John E. Rolls with his boys who are about the age now that Tad and Willie were when they left for Washington. Your residence here is kept in good order. Mr. Tilton has no children to ruin things.”14

Willie’s presence continued to be felt by both his parents. His mother told her half-sister, Emilie Todd Helm, “He comes to me every night, and stands at the foot of my bed with the same sweet, adorable smile he has always had; he does not always come alone; little Eddie is sometimes with him and twice he has come with our brother Alec, he tells me he loves his Uncle Alec and is with him most of the time. You cannot dream of the comfort this gives me. When I thought of my little son in immensity, alone, without his mother to direct him, no one to hold his little hand in loving guidance, it nearly broke my heart.”15

Footnotes

- Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, “Six Months in the White House,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 19 (Oct.-Jan., 1926-27): p. 48.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, p. 332

- Julia Taft Bayne, Tad Lincoln’s Father, p. 8-9.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage, p. 260.

- Daniel Mark Epstein, The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage, p. 368.

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume II, p. 299.

- Wayne Temple: Abraham Lincoln: From Skeptic to Prophet, p. 187.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 67.

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, p. 106-110.

- Ervin Chapman, Latest Light on Abraham Lincoln and War-time Memories, pp. 505-506.

- Chapman, Latest Light on Abraham Lincoln and War-time Memories, p. 503 (Dr. Gurley said he wrote out his remarks after the funeral – at the request of President Lincoln.)

- Benjamin Thomas, “The President Reads His Mail,” The Many Faces of Lincoln, p.132.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage, p. 266.

- Benjamin Thomas, “The President Reads His Mail,” The Many Faces of Lincoln, p.132.

- Katherine Helm, Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 227.

Visit

Mary Todd Lincoln

Robert Todd Lincoln

Thomas D. Lincoln

John Hay

John Hay’s Office

Guest Bedrooms

Julia Taft

Green Room

Attic

Rev. Phineas D. Gurley

Orville H. Browning

Emilie Todd Helm

George B. McClellan

Family Library

Prince of Wales Room

Abraham Lincoln’s Sons

East Room