Salmon P. Chase served as Secretary of the Treasury (1861-64), as a Senator from Ohio (Republican, 1849-55, 1861) and as Governor (1855-60). Former Whig, former Abolition Party founder, former Free Soiler, former Know-Nothing, and former Democrat, a Republican Chase was favored by some delegates for the 1860 nomination and by more radical Republicans to replace Lincoln in 1864. A Chase associate, Hugh McCulloch, later wrote that “personal relations between Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Chase were never cordial. They were about as unlike in appearance, in education, manners, in taste, and temperament, as two eminent men could be.”1 But Mr. Lincoln did admire Chase, once saying, that “Chase is about one and a half times bigger than any other man that I ever knew.”2

Chase was a bureaucratic meddler whose interests ranged well beyond the Treasury Department. He often involved himself in policy regarding the army and allied himself with Republican Radicals in the Senate while using Treasury agents to set up a political network around the country. He was a strong and persistent advocate of black rights and a consistent advocate of emancipation. In his diary, Chase recorded the cabinet meeting on September 22, 1862 where the draft Emancipation Proclamation was approved:

“To Department about nine. State Department messenger came, with notice to Heads of Departments to meet at 12.—Received sundry callers.—Went to White House.

All the members of the Cabinet were in attendance. There was some general talk; and the President mentioned that Artemus War had sent him his book. Proposed to read a chapter which he thought very funny. Read it, and seemed to enjoy it very much—the Heads also (except Stanton) of course. The Chapter was ‘Highhanded Outrage at Utica.’

The President then took a graver tone and said:—

‘Gentlemen: I have, as you are aware, thought a great deal about the relation of this war to Slavery; and you all remember that, several weeks ago, I read to you an Order I had prepared on this subject, which, on account of objections made by some of you, was not issued. Ever since then, my mind has been much occupied with this subject, and I have thought all along that the time for action on it might very probably come. I think the time has come now. I wish it were a better time. I wish that we were in a better condition. The action of the army against the rebels had not been quite what I should have best liked. But they have been driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion. When the rebel army was at Frederick, I determined, as soon as it should be driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion, to issue a Proclamation of Emancipation such as I thought most likely to be useful. I said nothing to any one; but I made the promise to myself, and (hesitating a little)—to my Maker. The rebel army is now driven out, and I am going to fulfill that promise. I have got you together to hear what I have written down. I do not wish your advice about the main matter—for that I have determined for myself. This I say without intending any thing but respect for any one of you. But I already know the views of each on this question. They have been heretofore expressed, and I have considered them as thoroughly and carefully as I can. What I have written is that which my reflections have determined me to say. If there is anything in the expressions I use, or in any other minor matter, which anyone of you thinks had best be changed, I shall be glad to receive the suggestions. One other observation I will make. I know very well that many others might, in this matter, as in others, do better than I can; and if I were satisfied that the public confidence was more fully possessed by any one of them than by me, and knew of any Constitutional way in which he could be put in my place, he should have it. I would gladly yield it to him. But though I believe that I have not so much of the confidence of the people as I had some time since, I do not know that, all things considered, any other person has more; and, however this may be, there is no way in which I can have any other man put where I am. I am here. I must do the best I can, and bear the responsibility of taking the course which I feel I ought to take.

The President then proceeded to read his Emancipation Proclamation, making remarks on the several parts as he went on, and showing that he had fully considered the whole subject, in all lights under which it had been presented to him.

After he had closed, Gov. Seward said: ‘The general question having been decided, nothing can be said further about that. Would it not, however, make the Proclamation more clear and decided, to leave out all reference to the act being sustained during the incumbency of the present President; and not merely say that the Government ‘recognizes,’ but that it will maintain, the freedom it proclaims?’

I followed, saying: ‘What you have said, Mr. President, fully satisfies me that you have given to every proposition which has been made, a kind and candid consideration. And you have now expressed the conclusion to which you have arrived, clearly and distinctly. This it was your right, and under your oath of office your duty, to do. The Proclamation does not, indeed, mark out exactly the course I should myself prefer. But I am ready to take it just as it is written, and to stand by it with all my heart. I think, however, the suggestions of Gov. Seward very judicious, and shall be glad to have them adopted.’

The President then asked us severally our opinions as to modification proposed, saying that he did not care much about the phrases he had used. Everyone favored the modification and it was adopted. Gov. Seward then proposed that in the passage relating to colonization, some language should be introduced to show that the colonization proposed was to be only with the consent of the colonists, and the consent of the States in which colonies might be attempted. This, too, was agreed to; and no other modification was proposed. Mr. Blair then said that the question having been decided, he would make no objection to issuing the Proclamation; but he would ask to have his paper, presented some days since, against the policy, filed with the Proclamation. The President consented to this readily. And then Mr. Blair went on to say that he was afraid of the influence of the Proclamation on the Border States and the Army, and stated at some length the grounds of his apprehensions. He disclaimed most expressly, however, all objection to Emancipation per se, saying he had always been personally in favor it—always ready for immediate Emancipation in the midst of Slave States, rather than submit to the perpetuation of the system.3

Chase’s humorlessness and raw ambition impaired his relationship with the President. He took a particularly dim view of the President’s jokes and stories. As Treasury Secretary, he presided over the financing of the war effort and passage of the Legal Tender Act of 1862 which authorized greenbacks. He also presided over the growth of a political empire through the expansion of the number of Treasury agents around the country. On May 17,1864, Gideon Welles and Senator Justin S. Morrill discussed the subject: “The whole proceeding is a disgrace and wickedness. I agree with Governor M. that the Secretary of the Treasury has enough to do attend to the finances without going into the cotton trade. But Chase is very ambitious and very fond of power. He has, moreover, the fault of most of our politicians, who believe that the patronage of office, or bestowment of public favors, is a source of popularity. It is the reverse, as he will learn.”4 Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Maunsell B. Field noted that Chase “was a man of extremely nervous temperament, and he would sometimes be very violent, and occasionally even unjust, while swept by a gale of passion. On one occasion Senator [William P. Fessenden] came into my room in a terrible rage, occasioned by a scolding which he had received from the Secretary.”5

Chase’s political machinations were maladroit, as Congressman George Julian recalled: “Early in January [1864] an organized movement was set on foot in the interest of Mr. Chase for the Presidency, and I was made a member of a central Committee which was appointed for the purpose of aiding the enterprise. I was a decided friend of Mr. Chase, and as decidedly displeased with the hesitating military policy of the Administration; but on reflection I determined to withdraw from the committee and let the presidential matter drift. I had no time to devote to the business, and I found the committee inharmonious, and composed, in part, of men utterly unfit and unworthy to lead in such a movement. It was fearfully mismanaged. A confidential document know as the ‘Pomeroy circular,’ assailing Mr. Lincoln and urging the claims of Mr. Chase, was sent to numerous parties, and of course fell into the hands of Mr. Lincoln’s friends.”6 The result was one of Chase’s several offered resignations—which the president rejected—as he did suggestions that he should dismiss Chase: “Let him alone; he can do no more harm in here than he can outside.”7

In June, however, Chase balked at appointing an assistant secretary of the treasury for New York who was acceptable to New York’s leading politicians. “At the Department received a note from the President, saying that Senator [Edwin D. Morgan] strongly opposed the nomination of Mr. Field in place of Mr. [John]Cisco—replied asking an interview, but received no answer. He may not wish one or what is more probably allows himself to forget the request. He asks the nomination of R.S. Blatchford or Dudley S. Gregory, neither of whom, I fear, is the proper man to take charge of the office at this critical juncture; though either would be entirely acceptable to me personally. I fear Senator Morgan desires to make a political engine of the office, and loses sight in this desire of the necessities of the service,” Chase wrote in his diary on June 28, 1864. “Telegraphed Mr. Cisco urging him to withdraw resignation and serve at least another quarter; and wrote to President what I had done and why I could not honestly, in duty to him or the country, recommend at this time either of the names he had suggested.”8

The controversy came to a boil the next day, as Chase wrote in his diary: “Last evening I received Mr. Ciscos reply to my telegram consenting to withdraw his resignation. This morning I received the Presidents reply to my note. He says he did not accede to personal interview because useless-complains of the difficulties occasioned by his retention of Mr. Barney and the appointment of Judge Hogeboom, both considered as of the radical side and says he cannot go further in that direction by the appointment of Mr. Field[;] desires appt. made acceptable to Gov Morgan and those who think as he does. Will await Mr. Cisco’s action. I replied that I made no general distinction in appointments except friend and opponents of his administration and among the former none except degrees of fitness—that Mr. Cisco’s reply relieved the present difficulty; but as I could not help feeling that my position here was not agreeable to him and there was nothing in my office making me wish to retain it. I enclosed my resignation and should feel really relieved by its acceptance. I added that I would give my successor all the aid I could for his entrance upon the duties of the office. With this note I enclosed my resignation.”9

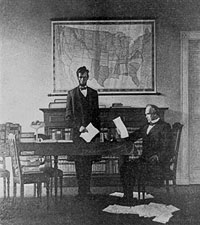

Two months after Chase was dismissed in mid-1864, President Lincoln agreed to meet with Maunsell B. Field to explain why he had not been nominated for the post of “Assistant Treasurer in New York City” to replace John J. Cisco. Mr. Lincoln denied that the reason was because he was a longtime Democrat. Instead, he explained:

“The Republican party in your state is divided into two factions, and I can’t afford to quarrel with either of them. By accident rather than by any design of mine, the radicals have got possession of the most important Federal offices in New York. I care nothing whatever about your personal politics. You were pressed by Mr. Chase and opposed by Senator ____. Had I, under these circumstances, consented to your appointment, it would have been another radical triumph, and I couldn’t afford one. That is all that there is about it, so far as you are concerned. But I’ll tell you what happened at the time between myself and Chase. One day, early in June, Chase came to me and said, ‘Mr. President, Cisco has resigned at New York, and I am going on there to see who is the best man to put into his place.’ Here Mr. Lincoln’s face assumed an indescribably droll expression, and, drawing his head toward mine, and placing his enormous hand upon my knee, he said, ‘That, you understand, was a peg that would fit in any hole!’ The President continued: ‘Well, Chase went to New York, and in due time returned, I suppose, but he did not come near me. In the mean time there was the fiercest contest waging for the vacant office that I remember since I have been in this place.’ (This is the manner in which Mr. Lincoln always referred to his position as President.) ‘I must confess that you were the most numerously indorsed, but ____ opposed you. The next time that I heard from Chase upon the subject was when he wrote to me requesting me to nominate you. I answered his communication, and asked him to come and see me, and talk over the matter. Instead of doing so, he wrote me again, saying that he would have you and nobody else. And so we fired letters at each other for two or three days. I offered to nominate either of three gentlemen who happened to be acceptable to Senator ____; but Chase objected to all of them. Finally, as I was sitting here at my desk one morning, with the room full of people, a letter from the Treasury Department was brought to me. I opened it, recognized Chase’s handwriting, read the first sentence, and inferred from its tenor, that this matter was in the way of satisfactory adjustment. I was truly glad of this, and, laying the envelope with its inclosure down upon the desk, went on talking. People were coming and going all the time till three o’clock, and I forgot all about Chase’s letter. At that hour it occurred to me that I would go down stairs and get a bit of lunch. My wife happened to be away, and they had failed to call me at the usual time. When I was sitting alone at table my thought reverted to Chase’s letter, and I determined to answer it just as soon as I should go up stairs again. Well, as soon as I was back here, I took pen and paper and prepared to write; but then it occurred to me that I might as well read the letter before I answered it. I took it out of the envelope for that purpose, and, as I did so, another inclosure fell from it upon the floor. I picked it up, read it, and said to myself, ‘Halloo, this is a horse of another color!’ It was his resignation. I put my pen into my mouth, and grit my teeth upon it. I did not long reflect. I very soon decided to accept it, and I nominated Dave Tod to succeed him.10

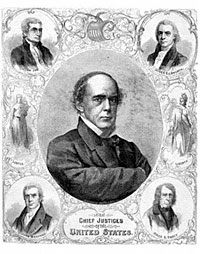

On December 6, 1864, Chase was appointed by President Lincoln to Supreme Court to replace the deceased Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. The President recognized Chase’s ceaseless ambition and chose to use it for the country’s benefit. In early 1864, President Lincoln told editor Henry Raymond: “Raymond, you were brought up on a farm, were you not? Then you know what a chin fly is. My brother and I were once ploughing corn on a Kentucky farm. I was driving the horse, and he was holding the plough. The horse was lazy; but on one occasion rushed across the field so that I, with my long legs, could scarcely keep up with him. On reaching the end of the furrow, I found a enormous chin fly fastened upon him, and knocked it off. My brother asked me what I did that for. I told him I didn’t want the old horse bitten in that way. ‘Why,’ said my brother, ‘that’s all that made him go!’ Now, if Mr. Chase has a presidential chin fly biting him, I am not going to knock it off, if it will only make his department go.”11

One benefit of Chase’s selection as chief justice was the presumption that he would uphold the Lincoln Administration’s actions during the war. President Lincoln told Massachusetts Congressman George S. Boutwell: “There are three reasons why he should be appointed and one reason why he should not be. In the first place, he occupies a larger space in the public mind, with reference to the office, than any other person. Then we want a man who will sustain the Legal Tender Act and the Proclamation of Emancipation. We cannot ask a candidate what he would do; and if we did and he should answer, we should only despise him for it. But he wants to be president, and if he doesn’t give that up it will be a great injury to him and a great injury to me. He can never be president.”12 On several issues, however — such as the printing of paper money and suppression of civil liberties — Chase’s “opinions as a jurist were the opposite his views as a statesman,” according to fellow Cabinet member John Usher.13

Subsequently, Chase presided over the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson. He later became a Democrat, breaking with Radical Republicans. He never lost his presidential ambitions — hoping for the Democratic nomination in 1868 and the Liberal Republican that went to Horace Greeley in 1872. Those ambitions were tempered by neither his Protestant piety or his social elitism. Daughter Kate Chase Sprague, wife of Rhode Island Senator William A. Sprague, was an indefatigable promoter of her father’s presidential hopes. Sprague himself was a wealthy Democrat, influential former governor who led one of the first northern regiments into Washington in April 1861, and disreputable businessman who undermined the Union war effort.

Footnotes

- Hugh McCulloch, Men and Measures of Half a Century, p. 188.

- Alice Hunt Sokoloff, Kate Chase for the Defense, p. 101.

- David Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase, p. 149-152.

- Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 34.

- Maunsell B. Field, Personal Recollections: Memories of Many Men and Some Women, p. 281.

- George Julian, Political Recollections, p. 236.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 125.

- Donald, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet, p. 218-219.

- Donald, p. 220-1.

- Maunsell B. Field, Personal Recollections: Memories of Many Men and Some Women, p. 302.

- Francis Brown, Raymond of the Times, p. 250.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, editors, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 38.

- Rufus Wilson, editor, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 377.

Visit

Mr. Lincoln’s Office

Treasury Department

Salmon P. Chase’s House

Henry Raymond

Andrew Johnson

William Pitt Fessenden

Hugh McCulloch

George Julian

Schuyler Colfax

John P. Usher

Gideon Welles

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Abraham Lincoln and Ohio

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Abraham Lincoln and Salmon P. Chase

The Cabinet (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Abraham Lincoln and Cotton

Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1860

1864 Patronage Problems (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Salmon P. Chase (Mr. Lincoln and Freedom)

Abraham Lincoln and Civil War Finance

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom

Mr. Lincoln and New York